Little House on the Prairie author Laura Ingalls Wilder was a real-life pioneer girl who endured tornadoes, blizzards, wildfires, malaria, and near-starvation, but her books were fictionalized, highly edited accounts of her life. What was the real story? Why did the family leave the house in the big woods? What were her true feelings about Native Americans? What happened in her marriage to Almanzo? How did Laura start writing? Author Caroline Fraser, drawing from letters, diaries, unfinished manuscripts, and interviews, spent years uncovering the true story for her acclaimed biography, Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Wilder’s story, writes Fraser in the book’s introduction, “is broader, stranger, and darker than her books, containing whole chapters she could scarcely bear to examine.”

Prairie Fires was chosen as one of Amazon’s Best Books of the Year, and Booklist called it “compelling, beautifully written . . . an unforgettable American story.” Vivian Gornik of The New Republic wrote, “Prairie Fires could not have been published at a more propitious time in our national life.”

Fraser is the editor of the Library of America edition of Wilder’s Little House books, and her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and the Los Angeles Times.

Metropolitan Books kindly supplied this interview with Caroline Fraser:

Many people feel like they know Laura Ingalls Wilder. Was her real life different from the one she portrayed in the books?

One of the reasons why I wanted to write this book is that I came to feel that “Laura” had almost been loved to death, sort of like a beloved doll or toy. Between the fictional Laura of the books and the even more heavily fictionalized girl of the TV show, we’ve tended to lose sight of the fact that Laura Ingalls Wilder was a real person who was complicated and intense.

She’s also someone whose life opens a window on everything from frontier history and the Plains Indian wars to the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. Her real life is even more remarkable, in some ways, than the story in her books, which ended at age 18 with her marriage.

How did you become interested in Wilder’s story?

I was a fan as a kid and read the books over and over. They were some of my favorites, especially The Long Winter, which I just loved. They’re so absorbing—a world unto themselves—and comforting. That isn’t true for all readers, of course, but that was my experience.

They meant a lot to me because my family came from immigrant farmers and covered wagon people: on my mother’s side, Swedes and Norwegians who farmed in Minnesota and North Dakota, and on my father’s side, Germans who farmed about 50 miles from Pepin, Wisconsin, where Laura was born. So Laura’s story felt like my story, somehow—and I know that generations of other readers have felt the same way.

I started writing about Wilder in the early 1990s, when a biography of Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, was published. It claimed that Rose was the ghost writer of the Little House books. I was curious and kind of skeptical about that, so I started looking at Wilder’s handwritten manuscripts. And I ended up writing a long piece about Wilder for The New York Review of Books. Eventually I edited the Library of America’s two-volume edition of the Little House books and found the history so fascinating I didn’t want to stop.

What was the most surprising discovery you made during your research for Prairie Fires?

There were a lot of surprises, including pretty basic things, such as the realization of the fact that Wilder—who is so strongly associated with the West—spent most of her adult life in the American South. That became very clear to me when I went to the Ozarks and Mansfield, Missouri, for the first time. I don’t think the South influenced her work, per se, but I do believe that her long exile from her family in the Dakotas helped to inspire the nostalgia for her past in the Little House books. And that was huge.

Another startling discovery was the fact that Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, was a notorious yellow journalist, who taught her mother the tricks of the trade. Lane learned at the foot of a master, Fremont Older, who was the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin and a friend of William Randolph Hearst’s. Lane wrote an invented “autobiography” of Charlie Chaplin—he threatened to sue her when she tried to publish it as a book—as well as dubious biographies of Henry Ford, Jack London, and Herbert Hoover.

The fact that Wilder was influenced by this is shown by one of the very tall tales she told in her famous 1937 Detroit book fair speech, in which she claimed that her father was involved in hunting and executing the “Bloody Benders,” who were serial killers on the Great Plains. The Benders were real, but her father’s exploits weren’t. It’s interesting because Wilder would insist—in that speech and elsewhere—that her books (although published as novels!) were “all true.”

Why was Wilder’s relationship with her daughter Rose so fraught?

Rose is just a fascinating character in her own right—colorful, driven, immensely talented and also kind of tortured. For many years, she was a better-known writer than her mother, writing for the Saturday Evening Post and a lot of national magazines. She almost bullied her mother to write the Little House books, and it’s clear that they would not have been published without Rose, her professional connections, her editing, and her guidance.

I think one of the stories within a story of Prairie Fires is the drama of the relationship between these two women. It’s kind of unprecedented: I can’t think of another mother-daughter literary collaboration like it. It was a sort of battle between the two of them over whose vision and voice was going to prevail. Rose even went so far as to write two novels of her own based on her mother’s material (which Laura did not appreciate). But it was Laura whose voice won out, because she was so authentic. And it was her story.

Their relationship suffered due to their collaboration, I think. Rose, who had lived on her parents’ farm for years, ended up moving east, and didn’t see her father for years before he died. There was a lot of tension there, never resolved. It’s kind of ironic that the Little House books, which are so wonderful in portraying a close-knit, loving family, came from such a dysfunctional relationship.

What did Wilder think about the expansion of the world of the Little House books into popular culture—movies, TV, toys?

Virtually all of the adaptations for film and TV happened after Wilder died in 1957. Wilder never owned a television, and she told a friend that she didn’t like the one adaptation she saw, of The Long Winter.

The famous long-running TV show starring (and produced and directed by) Michael Landon didn’t come along until after Wilder and her daughter were both gone. Rose’s heir, Roger MacBride, optioned the TV rights several years before he ran for president in 1976. MacBride, of course, never met Wilder and was not related to her, and I have to think she would have been horrified at the liberties that were taken on that show. She fictionalized her life to some extent, but always tried to be true to her memories.

Wilder wasn’t completely opposed to products being developed from the books—there was a plan she approved, at one point, for a clothing line tied to the books. But it never happened.

How did Laura feel about the Great Plains?

Laura loved wilderness, open space, solitude, and above all the prairies. And that feeling lifts the Little House books beyond mere storytelling or adventure and gives them a lot of their resonance. I’ve written before about the relationship between Wilder’s descriptions of wildlife and wilderness and the classic American treatment of those topics in Emerson and Thoreau and Willa Cather—she’s a classic part of that tradition.

What was Wilder’s experience with the Native Americans who shared the land with her family as she was growing up? Did this differ from conventional views of other white settlers on the plains at that time?

As a child, Laura clearly feared Indians and was also deeply fascinated by them. And it has to be said that she knew nothing about Indian history or culture or even much about the specific role her family played in displacing the Osage. Her adult view is made up of racist and romantic stereotypes. The Indians in Little House on the Prairie are caricatures, not characters. That’s regrettable. But it also tells us a lot about white settlers and the prevailing attitudes.

In Prairie Fires, I tried to bring out some of the historical context for white women’s fear of Indians, much of which had to be related to what Wilder called “the Minnesota massacre.” Now known as the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, it happened a few years before she was born but clearly influenced how whites saw Indians at that time.

I think Wilder’s attitude did differ from the standard white view in one key respect, which is that she saw the similarity between Indians and white settlers. They both had to cope with the elements, which tended to foster a peculiar kind of stoicism that she very much admired. She appreciated Indians’ ability to deal with whatever nature threw at you without whining or complaining or quitting. And she once said of a beautiful river on the Dakota Plains, “If I had been the Indians I would have scalped more white folks before I ever would have left it.” Which was kind of extraordinary for a woman of her time.

What was Wilder’s relationship with her father like?

Wilder adored her father, and the feeling was clearly mutual. Laura’s sister Mary seems to have taken after her mother—she was quiet, patient, even pious. But Laura was more rambunctious, hot-tempered, and I think she identified with her father because they were so alike. They both loved solitude and adventure and wilderness.

Charles Ingalls was fun-loving and musical and a great storyteller. He had an incredible gift for playing the fiddle, and though Laura never learned a musical instrument, she had an amazing recall for the songs he used to play. She was one of those people who had a song for every occasion.

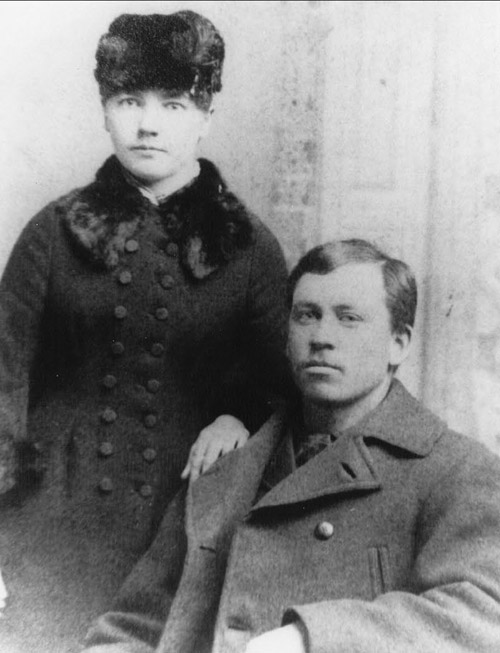

And they were both gifted writers. We don’t have a lot of letters written by Charles Ingalls, but the few things we do have are so moving and funny. There was one letter he wrote to his future son-in-law, Almanzo, and his brother Royal, when Almanzo and Laura were engaged—and he talks about the prairie winds and the blizzards, and how the wind makes his hair stand on end, just like in the Little House books.

Was the depiction of life on the frontier in the Little House books accurate?

It seems to have been very accurate, up to a point. Wilder left a lot of things out, sometimes because she felt they weren’t appropriate for children. In the books published during her lifetime, she never even hinted at anything having to do with bodily functions or sexuality. She would have found that distasteful. In the unpublished manuscript she left out the first four years of her marriage, though she wrote about childbirth in such vivid language that the editors cut some of it before the book came out.

But she also left things out to burnish her story. She could describe vividly and memorably how her father built a log cabin or made bullets or cleaned his gun, but she ruthlessly cut entire chapters of their life that did not reflect well on her parents. When you look at Charles Ingalls’s actual life, there were a lot of struggles, debts, even a kind of aimless quality—and she left all of that out. She wrote the Little House books as a memorial to her parents, and she didn’t want anything to take away from that. The result, of course, is that the Little House books promote this wonderful, successful image of settlement and homesteading. Much of it is accurate. But the real story is way more complicated.