Fame is the foodstuff of modern culture. Andy Warhol once famously suggested everyone should enjoy at least 15 minutes of it during their lifetime. At the age of 17, fame hit George Harrison like a tsunami. As the youngest member of the world’s most popular band, he was bombarded with global celebrity and, along with it, the usual temptations—money, girls, drugs, etc. He quite literally had it all.

But during the height of the insanity surrounding The Beatles, George discovered a spiritual side to life that became more important to him than being a famous celebrity, and far more stimulating than any drug could ever be. As a result, the desire to know God became the guiding light both in his life and his music.

George’s personal spiritual odyssey is beautifully chronicled in Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison, by Joshua M. Greene, recently released in paperback by Wiley.

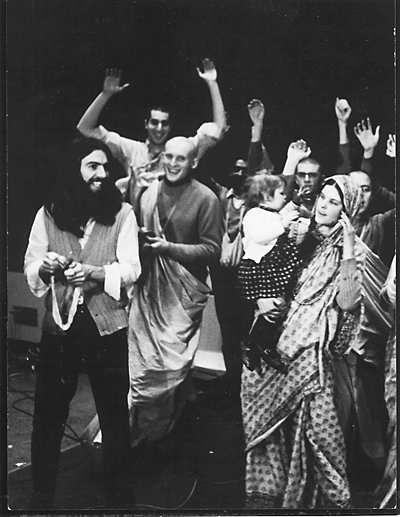

Greene had a chance encounter at the age of 19 with George. A spiritual seeker and budding musician, Greene wandered into the Hare Krishna temple in London one day, only to find himself quickly bundled off to Apple Studios to join the support band for George’s recording of “The Hare Krishna Mantra,” a blend of sacred chanting and modern melody that hit the Top Ten in England soon after being released in 1969.

According to Greene’s book, George described seeing the Radha Krishna Temple performing the song on England’s popular television show Top of the Pops as one of the greatest thrills of his life. I remember the show well myself. The infectious joy of the shaven headed, dancing devotees was quite a revelation (especially as half the studio audience was attempting to do the Twist).

Greene stayed with the Hare Krishna movement for 13 years before leaving to become a writer, filmmaker, and teacher of religious studies at Hofstra University on Long Island. His fond portrait of George Harrison’s spiritual and musical life is compiled from his own memories and detailed interviews with George’s friends, family, and fellow musicians. It shows George to be a deeply sensitive soul who sometimes struggled to balance his desire for simplicity and closeness to God with the complicated demands of celebrity.

George, it turns out, also found it difficult to express himself musically through The Beatles. Quickly dubbed the “quiet one,” he was often overshadowed by the more dominating personalities of John and Paul, the self-anointed writing team for the band, and only a few of his songs made it onto Beatles’ recordings. But Greene reveals that behind the scenes George was responsible for much of the creative recording techniques and sound innovation that made The Beatles’ music so unique.

It was George who first discovered eastern scales and instruments. Sitar master Ravi Shankar, who later became George’s close friend and musical mentor, comically recalled his distress at hearing George’s first attempts at plucking the sitar on “Norwegian Wood.” “Just imagine some Indian villager trying to play the violin,” he lamented, “when you know what it should sound like.” After the breakup of The Beatles, George’s creativity took flight and he amazed everyone by immediately releasing the triple album All Things Must Pass.

Greene also describes how George was the first to experiment with psychedelic drugs when his dentist spiked his coffee with LSD at a dinner party (only in the ’60s!). George later described the experience as being like “living a thousand years in ten minutes” and told a reporter from Rolling Stone magazine, “Up until LSD I never realized that there was anything beyond this everyday state of consciousness. . . . The first time I took it, it just blew everything away. I had such an overwhelming feeling of well-being, that there was a God, and I could see him in every blade of grass.” George’s enchantment with mind-expanding drugs and the hippy scene soon faded as he sought a less damaging and more reliable path to higher consciousness.

On a 1967 trip to Kashmir with his new wife, Patti Boyd, and Ravi Shankar, George read the writings of Indian saints Swami Vivekanda and Paramahansa Yogananda, whose book Autobiography of a Yogi later became a must read for every budding western spiritual seeker. “At last,” he said, “I’ve found someone who makes sense.” He discovered how meditation could unfold marvelous abilities lying dormant within the human soul.

Shortly after his return to England, George met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who had left India in 1957 to spread his message of inner peace and bliss through Transcendental Meditation. Maharishi invited George and his friends to a ten-day seminar in Bangor, North Wales, where all four Beatles and their wives and girlfriends learned the art of meditation. A few weeks later they traveled to Rishikesh on the banks of the sacred river Ganges in order to further their studies with Maharishi. While there, John and Paul wrote over 40 songs, many of which would appear on the White Album and Abbey Road. George preferred to spend his time meditating.

Back in England, The Beatles became embroiled in the creative anarchy known as Apple Corporation. Although this period produced some of their best work, the pressure of doing business as well as making music and their obviously diverging interests eventually led to the break-up of the band. In the middle of this chaos, George met a young shaven-headed American Hari Krishna disciple called Shyamsundar. Impressed by Shyamsundar’s humor and his simple devotion to God, George became a frequent visitor to the Krishna temple, where he joined the devotees in their daily chanting of Krishna’s name. Swami Bhaktivedanta (Prabhupada), the founder of the Hare Krishna movement, joined Maharishi as one of George’s principal spiritual mentors. Through meditation and devotional chanting, George acquired the tools he needed in his search for truth. When he died in 2001, he passed away peacefully and unafraid, confident of his merging with the Divine.

Joshua Greene’s narrative skillfully weaves together George’s music and spiritual life. He reveals the meaning behind his most famous songs (“Something,” for example, is a hymn to Lord Krishna transposed into a love song for his wife Patti). Above all, Greene captures the beauty of George’s soul, how he quickly found his purpose in life as a spiritual seeker and how he used his popularity to inspire others find the same truth.

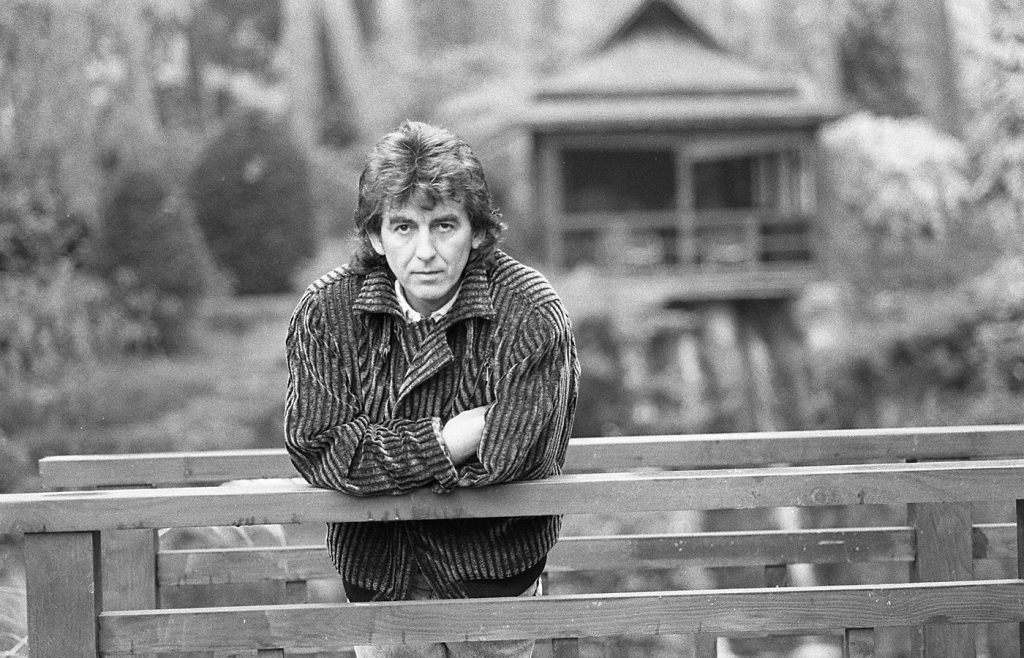

I was fortunate to work with George Harrison on the benefit for the Natural Law Party at London’s Albert Hall during the1992 parliamentary election campaign. What impressed me most of all (apart from his wry humor) was his obvious unconcern with his legendary fame. When I first met him at a rehearsal, he stuck out his hand and said, “Hi, I’m George Harrison.” As one of the most well-known people in the world, it seemed an unnecessary gesture. But I think it was typical of his humility. He was simply not interested in being famous.

In fact, he spent much of his life trying to be un-famous. His principle desire in life was to know God. As Greene’s book reveals, he was as happy meditating or tending his garden as he was being a celebrity. If he could lead others towards God through his words and music, then he was truly happy. And that is why we all loved him so much.

Tony Ellis is a Fairfield based writer and poet (www.tonyellis.com). He is eternally grateful to George Harrison for inviting him onstage at the Albert Hall while George played “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” his favorite Beatle’s song.