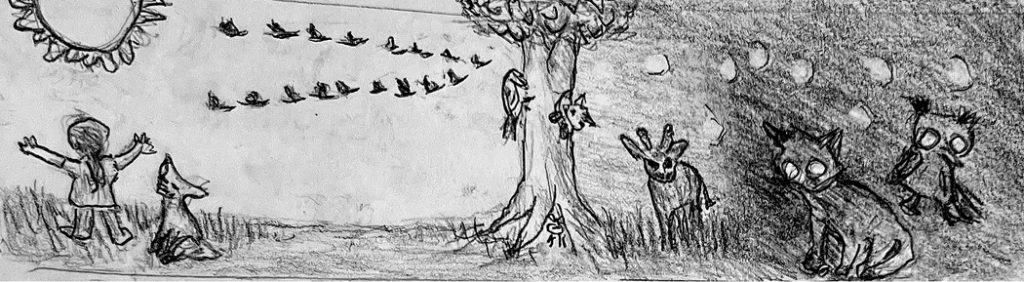

The sun is setting, and I hear the wild honking of a large flock of geese flying in from the north. In the darkening twilight, they fly a wide circle over our pond and settle, splashing onto the water. It’s pure magic of sight and sound riding the twilight—a gift from nature. Last week, in one night, 53 million birds migrated across Iowa. At night.

The earth has been rotating on its axis since it first formed, bathed in our sun’s bright light and held in place by the sun’s gravity. Rotating on its axis, day to night, for billions of years, with only fires, stars, planets, the moon, the sky-spanning crescent of the Milky Way, and the bright white flashes of lightning to light up the dark night sky.

For millions of years, every living thing on the planet thrived in daily cycles of dark and light, including humans. Over time, this 24-hour cycle of night and day, the circadian rhythm, structured the DNA for all life on the planet.

About 500 million years ago, eyes and ears began to develop in one form or another. Eyes allowed everybody to use light and dark cycles for mating, hunting (or hiding), resting, and scavenging for food. Eyes processed light. Ears allowed hunters and prey to live and reproduce in the dark. Bats developed echolocation to hunt at night.

With eyes, bees, birds, butterflies, fireflies (which are actually beetles), 60 percent of mammals, and even fish and whales could use the sun of days and the dark of nights to survive and thrive. To be safe. To find food. To mate. And to ensure their species’ futures with eggs, grubs, and babies safe in darkness, hidden in nests and under leaves, and even under soil.

With eyes, bees, birds, butterflies, fireflies (which are actually beetles), 60 percent of mammals, and even fish and whales could use the sun of days and the dark of nights to survive and thrive. To be safe. To find food. To mate. And to ensure their species’ futures with eggs, grubs, and babies safe in darkness, hidden in nests and under leaves, and even under soil.

We all know about animals using darkness. Take cats, for instance, who hunt in the dark: “Cats have an extra membrane in the eye, the tapedum lucidum, that allows twilight rays to pass over the retina twice for maximum harnessing of light,” writes Johan Eklöf in The Darkness Manifesto (a fabulous read, by the way). “Who hasn’t at some point seen a pair of cat eyes shining in the night?”

The natural use of day and night was the story of the world and all its inhabitants for millions of years, until . . .

Ta-dah!! About 150 years ago, we clever humans discovered that the staggering power of lightning could be generated and sent through wires!

We invented light bulbs to capture its immense glowing light, calling it electricity, and we began to light up our world’s nights. The technical term that today’s science gives this darkness-eating light—now that it has become a planet-wide problem—is “artificial light at night” or ALAN.

The International Dark-Sky Association (DarkSky.org) estimates that one third of all outdoor lighting in the U.S. is wasted, fulfilling no purpose. But even worse than that, artificial light causes hundreds of problems for the ecosystem. Here are just a few instances.

Light coming from hotels along beaches confuses new sea turtle hatchlings, drawing the little ones away from the water so they never reach the sea. Instead, they wander disoriented on land, where their survival rate is slim.

In the insect world, many species of moths that navigate by the moon become hypnotized by bright, artificial light, so they don’t mate or hunt. This is just one part of the “insect apocalypse” that is multiplying every year. One study done in Germany found a decline of 100 billion in insect numbers every year. Insects pollinate our plants and trees—we need them for our food!

Coral reefs, which send out their gametes to spawn by the phases of the moon, become confused when the moon is obscured by skyglow over coastal cities. Spawning time stretches to two weeks instead of three days, creating less new coral. The same happens for other inhabitants of the reef. (See “Why light pollution threatens life” with Johan Eklöf on YouTube.)

We are risking putting nature out of business. Closing the shop. And we are, at last, coming to understand that we are only one part of the natural world, and like all the rest of its inhabitants, we need the nocturnal side of every day as much as we need the sunny side to survive.

“The biological clock, our circadian rhythm, is ancient and completely fundamental,” writes Eklöf in The Darkness Manifesto. “Every organism makes use of the preprogrammed clock in different ways. It’s light and darkness that calibrate the biological clock. Artificial light from lamps, headlights, and floodlights was not in the equation.”

Fortunately, people all over the world are waking up to the issue posed by artifical light. And it’s easy to make a difference. Here are three simple steps to take:

- Don’t leave outdoor lights on all night. Shade your outdoor lights and put them on a timer so they only turn on when necessary.

- Reduce the amount of light by using lower-wattage amber LEDs.

- Ask your city, local businesses, and schools to reduce bright outdoor lighting.

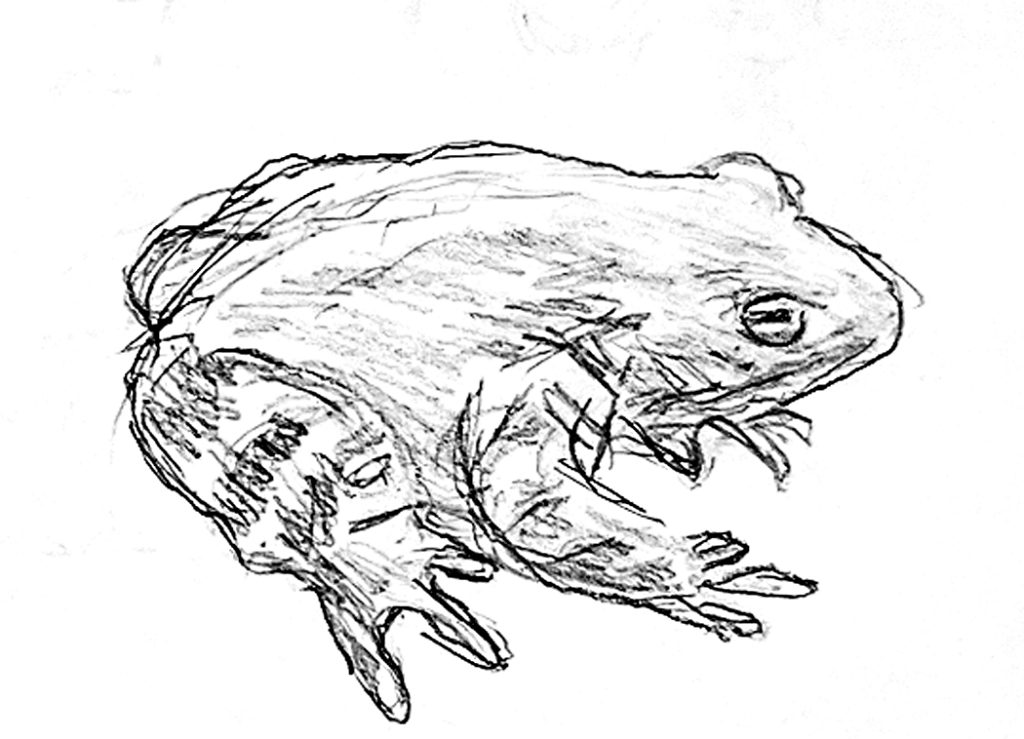

If you’d like to help, go to DarkSky.org and take a few minutes to become an advocate, or contact us at darksky.fairfield@gmail.com. We welcome pictures and recordings of your frogs, birds, and fire beetles. Bats, too, but they are very difficult to record.