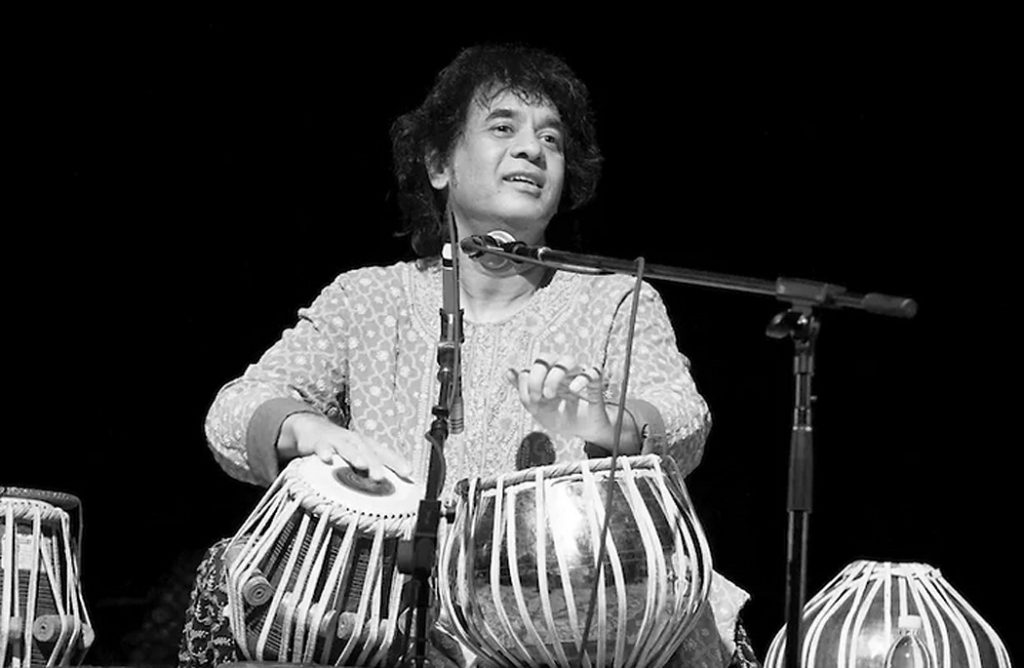

Zakir Hussain and the Masters of Percussion promise a rare feast of aural and rhythmic delight in Fairfield on Friday, March 31, 2023, at the Sondheim Center for the Performing Arts.

Zakir Hussain descends from generations of drummers in India. His father, tabla legend Ustad Alla Rakha, was revered for his tabla prowess and for bringing the instrument to the world. The tabla is an instrument of supreme beauty, with its low woomp, the liquid fingertip taps, the overtones, and a seemingly infinite range of possibilities in between. Subtle, forceful, plaintive, flowing—percussion that sings and dances, but also a great, subtle supporting instrument.

Zakir was a child prodigy, touring by the age of 12. He came to the United States in 1970 with Ravi Shankar, and that led to an international career that continues today, with as many as 150 concert dates a year. In addition to his current Masters of Percussion itinerary, Zakir will be doing some dates with Bela Fleck and Edgar Meyer, and a tour with Shakti, a group he joined in the 1970s.

He has collaborated with George Harrison (Living in the Material World), Jean-Luc Ponty, Yo-Yo Ma, Van Morrison, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Pat Martino, Dave Holland, Pharaoh Sanders, Tito Puente, Jack Bruce, Charles Lloyd, Billy Cobham, Bill Laswell, and many more.

Last year, he was awarded the international Kyoto Prize. This year, the government of India bestowed upon him one of its highest honors, the Padma Vibhushan, given for “exceptional and distinguished service.” Added to that are a Grammy for his work with the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart on the Planet Drum project and countless awards for his Indian classical music performances and recordings. Humble about it all, he often says he hopes to live up to the honors and to keep exploring musical possibilities. And that is a blessing for us all.

I caught up with Mr. Hussain on the West Coast leg of his current tour. He was about to head out for an afternoon concert in Phoenix.

James Moore: Welcome to Fairfield. You’re coming to a community with a radio station (KHOE 90.5 FM) that plays Gandharva music every night and that airs Gandharva music 24/7. How’s it going with your West Coast tour?

Zakir Hussain: First of all, a big namaste and hello to the listeners of KHOE and Mr. James Moore. You’ve just, like, put me up so high. . . . I mean, that’s a big build-up to live up to. My deep gratitude, Mr. Moore, for mentioning my father, Ustad Alla Rakha, whose hands have shaped me and guided me and still do from where he is up there in the heavenly abode. And I’m really looking forward to coming to Iowa and visiting with the audiences there. I have to say, though, that in the mid-80s, I did come to Iowa. I came to the Maharishi University and performed there with an Indian classical musician. Since then, I haven’t been there, so it’s long overdue.

One thing I want to mention is that you’ve won countless awards for playing classical Indian music. I guess it’s called Hindustani. We refer to it here as Gandharva music. When you came in the mid ’80s, was it to perform a Gandharva concert?

Yes. I came with a santoor maestro, that is, the hammer dulcimer player from India, Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma, who is one of the greatest musicians of India, who just this last May passed away at the age of 82. He was one of my mentors. We toured together at that time and Iowa was on our schedule. I did not know what to expect. I did not know where I was going, and we arrived and it felt like we were in devaloka [a kind of heaven].

And of course, Indian classical music—in North India, it is known as Hindustani; in South India it is known as Karnataka music—is connected with the devas and devis, gods and goddesses, who have apparently blessed India with this boon. So the music is connected with goddess Saraswati, who is shown playing the ancient vina instrument; Lord Krishna, who is playing the bansuri, or the bamboo flute; Lord Ganesha, who we rhythmists bow to, shown as playing the two-headed cylindrical drum called the mrdanga; and Lord Shiva, his father, is shown playing the damaru, from where the first sounds of the rhythm appeared that were then designed into a language of rhythm by Lord Ganesha. And that’s what we represent and pray through on all our instruments. It is not surprising that it is known as Gandharva music because of its roots.

You mentioned your father. I noticed there was a centenary celebration with six tabla players in honor of his life and career. And what an incredible night that was—everybody taking turns. I wonder if you could explain a little bit about the tabla.

Tabla is right now the premiere rhythm instrument of choice when it comes to playing traditional music in India. It has existed for a few hundred years. The repertoire, however, that it represents has existed for thousands of years. And was, as I mentioned, planted onto the mrdanga, the rhythm instrument of Lord Ganesha by him and developed by him and passed on to his devotees, who passed it on to their students, and so on and so forth, and it arrived in our world.

So the tabla is a present day representative of that repertoire and that line. It’s a two-headed drum, of course. One interesting thing about the tabla, it not only has the ability to be a rhythm instrument, but it’s also a harmonically friendly instrument to whatever instrument or singing or dancing that it accompanies, because it has tone and has ability to play the whole melodic scale while keeping the rhythm going. So therefore it doubles as both rhythmic and melodic support to the main artist that is performing. Apart from that, tabla has a solo repertoire that has existed for millennia, and we perform that repertoire as solo and as a multi-tiered performance with other tabla players, and offer our prayers doing that.

What you saw was the hundred-year centenary of my father’s birth, and there were like 200 tabla players who were there. . . . And I led it, of course, being the senior-most among all those disciples. One of them was my brother, and the other ones were just tabla students who had studied with my dad and we played together. What was interesting is that it was decided at the eleventh hour, so we did not plan on anything. We just sat down to play, and everybody was looking at me to move things along, and so I did.

Indian music is a form that relies mostly on spontaneous creativity—in other words, improvisation—it was built into our system to take an idea and build on it and improvise on it and create a beautiful bouquet out of various little petals and flowers and stuff that’s there for us to utilize. So that’s what we did (see Tribute to Alla Rakha). Indian classical music built on melodies (ragas) and rhythms (tala) is an ancient boon, and that’s what the tabla represents.

I have to say one thing about tala, if I may be allowed. It is said that Lord Shiva was called upon by the gods to come down and rid the earth of the demons, or asuras, which were occupying and destroying the earth. So Lord Shiva came down and he destroyed the asuras and drove them away from the earth. But in doing so, he got so caught up in it that his dance of destruction (Tandava) did not stop. When that happened, the earth itself was in danger of being mortally damaged. At that point, the gods went to Gauri, the consort of Lord Shiva, and requested that she go down to earth and do the dance of Lasya to calm Lord Shiva down. And so she came to earth and she did the dance of Lasya, and thus calmed Shiva down and earth survived. So we believe, in our mythology, rhythm mythology, that the first letter of the dance of destruction of Tandava (Ta) and the first letter of the dance of Lasya (La) were combined together to create the word “tala,” which means rhythm—which has both elements, constructive and destructive.

That’s beautiful. Can you give us a brief history on how the Masters of Percussion project started?

This actually began with my desire, and need, to spend some time with my father and learn more and get more transmission from him, because he had just decided that he wanted to cut down his touring with Ravi Shankarji. He was in his late 60s and felt he wanted to stay in Mumbai and just teach students.

That created a little bit of a problem for me, because I was living in California and teaching at the Ali Akbar College of Music. I always saw my father when he was here with Ravi Shankarji and could spend time with him. So I asked my father if he would be interested instead in doing a small tour every other year with me, and he thankfully said yes. So we arranged the first tour with him and me and a sarangi (a bowed melody instrument) player, Sultan Khan, whose son, incidentally, is part of this tour.

I thought, okay, this is fine. We’ll get to do this and that’ll be it. But it turned out to be a big success. And also it was great to spend so many weeks with my father, and learn more and relearn stuff, and come to a better understanding of the repertoire. It was one of the most joyous times in my life.

But what happened was, there was more interest in being able to continue these tours, so I arranged another one, and he came again. After that, he said he was getting a little too old to do this, so he suggested that I should showcase rarely heard rhythm traditions from India. There are so many different rhythmic traditions. There are about 200-odd percussion instruments in India and about 80 different rhythmic traditions that exist.

And so I went looking for these great maestros all over India and started bringing them on Masters of Percussion tours over the years. This all started around 1986-87, and then sometime around 2010, I decided that we should expand the Masters of Percussion stage and include masters of rhythm traditions from outside of India as well, because there are so many of them all over the world. And so we started bringing musicians from Iran, from the Middle East, from Africa, from Japan, from Europe, also jazz drummers, and so on and so forth. So Masters of Percussion prospered and has been going on every other year.

This version, we have a great percussionist from Uzbekistan and another one from Colombia/Brazil, and a folk drummer from central India, and myself, and a melody player, sarangi maestro Sabir Khan, who is the son of the maestro who came for the first, second, third, and fourth, and even the fifth Masters of Percussion, so there is some continuity there. And some new freshness that’s being represented.

What’s interesting is that all the percussionists are performing in the same tradition that Indian repertoire is based in—and that is improvising. So we have an idea, a thought that we put on the stage at the beginning of the evening, and then we explore that, spontaneously each one adding their thoughts behind the process, and thus build a performance that is inclusive of the audience that sits with us. And what’s interesting is that when it’s all done, it’s an experience specially and intimately shared by us that will never happen in this way again. And so it’s very personal and very intimate.

What a treat that our community will have the pleasure of your company. I want to ask in closing: You’ve played with a lot of different people—are there any stories you can share? I know George Harrison said something to you when you were interested in becoming a drummer. [Chuckles] That was a lesson learned. It was an important one. My God, I have been so lucky, so fortunate. Sometimes I wonder, did I really have so many interactions and contacts? How did this ever take place? And the only answer is that I was on the bus and when it took off, there I was. I was lucky these great musicians took my hand and took me on a path that has been wondrously revealing of incredible positive energy. And as you know, art, music, and dance are some of the few positive energies left on this planet—something by their nature installs in us, or creates in us, a feeling of happiness and peace and satisfaction and contentment. And so, it’s something I feel unbelievably blessed and fortunate to have been a part of.

Regarding George Harrison, first of all, I want to say something about another mentor of mine–Pandit Ravi Shankar. He took me on when I was 16 years old and took me on the road at the behest of my dad, who was doing other things at that time and said, take my son. And the great man said, yes, okay, so he took me along with him on tours. Ravi Shankar was the person I first played with in America. I came to play a concert with him, and that’s how I ended up in this country in 1970. It’s his guiding hand, along with my father’s, that has shaped the way I’ve turned out.

It was him who sent me to George Harrison, because George Harrison was given the task of producing, editing, and mixing the live concert recording of Ravi Shankar and my father and Ali Akbar Khan. He was doing that in a studio called Trident in London, Soho District. So Ravi Shankar told me, I’m sending you there in case George has any questions about the rhythm cycles of India and the melody, and when he cuts the piece down from two hours to 40 minutes for the LP, the cut is smooth and seamless and does not disturb the continuation of the music.

So I said, okay. I was there, and through the days we were working on the record, George was there. Then one day, I built up the courage to tell him, “Mr. Harrison, I would really like to be a rock drummer. I want to play drums.” I felt that was maybe the way to have a prosperous career and become famous and well known. As a young man, you wanted that adulation, and that’s what I was looking for. And George Harrison smiled, and he looked at me, and said:

“Satya, outside this studio, at my beck and call, there are at least 500 drummers who are waiting for me to call them, one better than the other. Why do you want to be 501, way back in the line? You have something special and unique to offer, and that’s why you’re sitting next to me here while they are outside. You have this incredible instrument that has the ability to transpose any language of rhythm that exists in this world, be it African, jazz, Middle Eastern, Latin-American, Afro-Cuban. I mean, you have the ability to be able to transpose all that information onto your tabla and bring it forth.

“Look at me. I play the sitar. I’ve learned from Ravi. But I will never dishonor the music that I’ve learned from my guru by playing it badly on the sitar. I would rather take that information and transpose it on my guitar and pay my homage and respect to that music through it. You have that ability. So go make that instrument into a world instrument. Make it speak all the rhythm languages that exist here. Make it a unified mode of a statement that represents the world of rhythm as opposed to just Indian rhythm. Bring that information forth and I’m sure your father will be proud. And you will be appreciated, loved, and always wanted as a percussionist.”

That kind of opened my eyes, and I started to do that. And here we are. Masters of Percussion is one element that came out of it. The other thing that spawned out of it was Planet Drum, which won the Grammy, and Global Drum Project, which also won a Grammy. And through Ravi Shankar’s influence, John McLaughlin came about, Bela Fleck, Edgar Meyer, and all these other great legends who have blessed me with their grace and their knowledge, and I hope the lessons continue. But there are still miles to go before I sleep.

[Chuckles] I love that about you—that when you’re receiving these awards, you say you just can’t wait to see what more can come out of this journey. What a perfect wrap up. The Masters of Percussion are in Fairfield Friday, March 31.

Thank you, sir, and take care of yourself. And my pronams to the great guru, the one that founded the university, the great Maharishi.

James Moore, who was music editor of The Iowa Source for seven years, is now station manager at KHOE 90.5 FM.