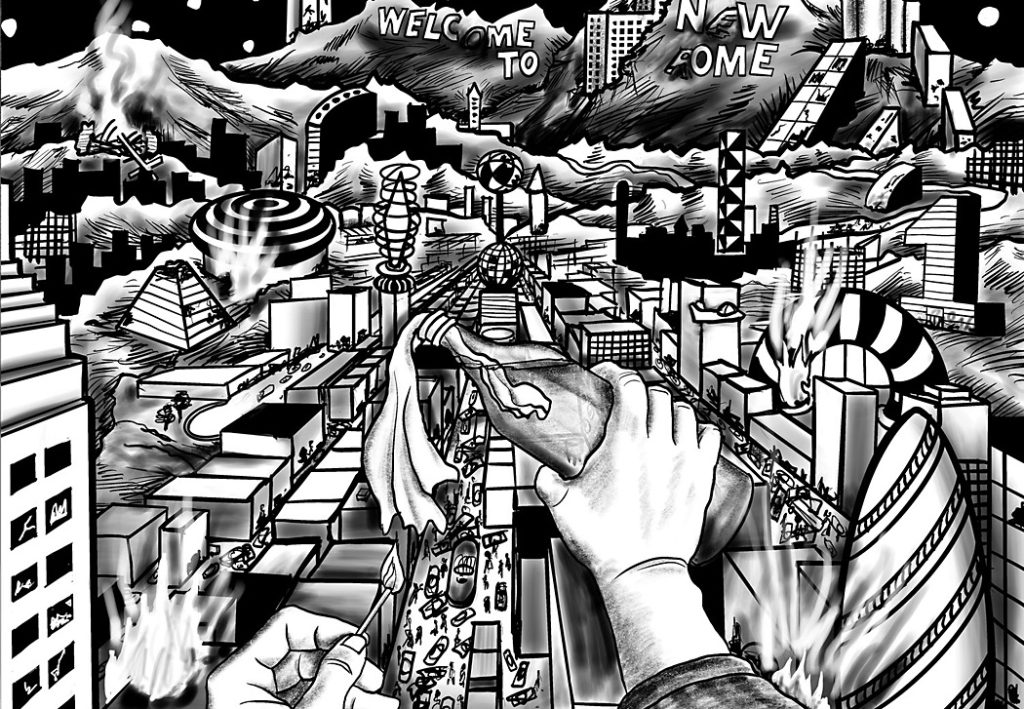

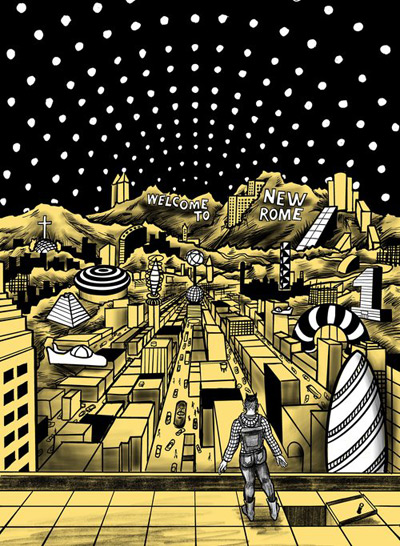

Here’s the pitch Fritz McDonald gives when asked to describe the graphic novel he co-created with Tom Jackson: “I tell them that 2184½ is like a cross between The Road Warrior and Catch-22.”

The description is apt. The story—set in a future dystopian America where the date never changes and facts are disposable—is reminiscent of a Mad Max adventure, while also capturing the satirical edge of Joseph Heller’s most famous novel. I talked with the two creators, both of whom live in Cedar Rapids, via Zoom to learn more about the origin of their partnership, the initial spark of their story, and their creative process.

Jackson and McDonald worked together at Stamats Communications in Cedar Rapids for many years—Jackson as a vice president and general manager, and McDonald as a writer (he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop) who steadily moved up through the company to also become a VP. Their friendship continued after Jackson—who has crafted a long and robust career as a visual artist—left Stamats.

“So I just stayed in touch with Fritz after I left the company and we would get together for lunch every now and then . . . and I began telling him, ‘Hey, I’ve got this story. This idea for a story,’” Jackson said. “I didn’t have the story, I had a concept for the story, and because I had the concept, I began doing drawings. And as I began developing it, Fritz became interested in it and agreed to join me to flesh out the story.”

The original spark for Jackson’s investigations of a future America was the event of September 11, 2001. At the time of the terrorist attacks, Jackson was exclusively creating abstract work. But the images of the Twin Towers site in the aftermath of the attack stuck with him and—further inspired by hearing the author John Updike on NPR suggest no one was capturing the American Zeitgeist—he turned his artistic attention to places like state fairs and junkyards to see if he could get to new way to think about America. At the same time, his interest in politics and journalism, and his dismay at the kind of fact-free commentary that surrounds modern American politics were shaping his ideas as well.

The original spark for Jackson’s investigations of a future America was the event of September 11, 2001. At the time of the terrorist attacks, Jackson was exclusively creating abstract work. But the images of the Twin Towers site in the aftermath of the attack stuck with him and—further inspired by hearing the author John Updike on NPR suggest no one was capturing the American Zeitgeist—he turned his artistic attention to places like state fairs and junkyards to see if he could get to new way to think about America. At the same time, his interest in politics and journalism, and his dismay at the kind of fact-free commentary that surrounds modern American politics were shaping his ideas as well.

As the politics of 2016 unfurled, he wanted to contribute to the conversation. He admired the covers of The New Yorker at the time, which were funny and biting, but he wasn’t sure single images were what we wanted to pursue.

“I wanted to do something that was bigger. Something that was epic. I wanted to tell a story that was really important to try and point out to people that, hey, if these things, if the bad trends now in America continued for 150, 160 years, what would the country look like? And that was kind of the germ of the story.”

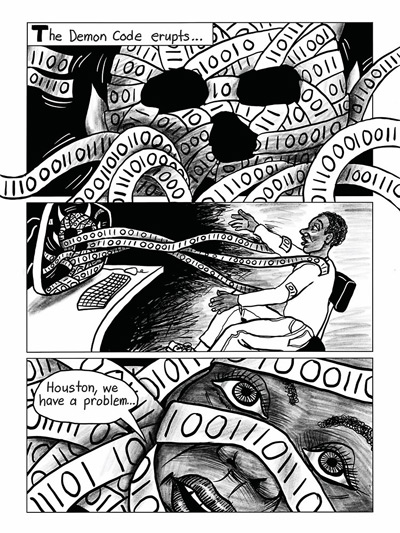

McDonald identifies the concept at the heart of the story this way: “The worst things that happen to a culture can become permanent.”

Jackson had created a visual style for the book, but that is just one aspect of what it takes to create a graphic novel set in a dystopian future. He and McDonald had plenty of additional work to do to get the story told.

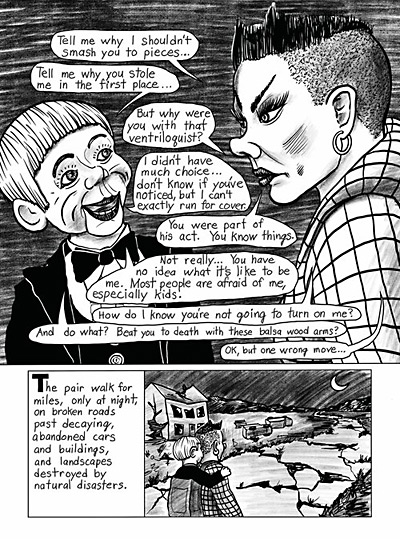

“We spent quite a while on the ideation phase of this, trying to think through the story, to create the characters, and world building, which I think in a graphic novel is really, really important, just like world-building in a sci-fi or fantasy movie is really, really important,” McDonald explained. “And so, we spent more than a year outlining, jotting ideas down, talking things out. Tom would keep drawing and I would take notes, and we would toss things back and forth with each other. And then, eventually, it started to gel into a story. And once we got it into a story at that point, then we settled on an outline version of it. I started writing and he basically started drawing.”

“We spent quite a while on the ideation phase of this, trying to think through the story, to create the characters, and world building, which I think in a graphic novel is really, really important, just like world-building in a sci-fi or fantasy movie is really, really important,” McDonald explained. “And so, we spent more than a year outlining, jotting ideas down, talking things out. Tom would keep drawing and I would take notes, and we would toss things back and forth with each other. And then, eventually, it started to gel into a story. And once we got it into a story at that point, then we settled on an outline version of it. I started writing and he basically started drawing.”

The collaborators shared work back and forth—the writing shaping the art and the art shaping the writing. It became a full-time endeavor. Jackson called it the “biggest project I’ve ever worked on.”

Part of the reason for that, McDonald explained, was because they were the only two working on the project.

“One of the things that we’ve learned the hard way,” he said, “is how much work the drawing takes. We discovered about halfway through, with him drawing the whole thing, that actually well-known graphic novelists have crews that they bring in to help them do this. . . . [Working as a team of two] is a wonderful way to work, but it’s also a very intense way to work on something. It’s kind of been our whole world for a while.”

“One of the things that we’ve learned the hard way,” he said, “is how much work the drawing takes. We discovered about halfway through, with him drawing the whole thing, that actually well-known graphic novelists have crews that they bring in to help them do this. . . . [Working as a team of two] is a wonderful way to work, but it’s also a very intense way to work on something. It’s kind of been our whole world for a while.”

It had been Jackson’s intention to draw the entire graphic novel using traditional materials, but it soon became clear that making changes would be far too difficult if his approach remained analogue. So he invested in some technology that allowed him to mimic the look of traditional drawing tools while also allowing him to create images in layers—meaning he could edit one portion of an image without destroying the entire scene.

Jackson cites influences from across art history—realists, modernists, those working in abstract styles, those who blend realism with surrealism, those innovating ways to make the line or image appear to escape the page—as foundational to the work he did in 2184½. These disparate influences are on display throughout the book, but Jackson blends them skillfully to create his own style that serves the story. The images are often striking, but they do not distract from the overall momentum of the tale being told.

After pitching the book to graphic novel and art house publishers, the duo ultimately decided to self-publish, which is not an uncommon approach for new graphic novel creators. And that meant they could keep production close to home.

“We decided to do it with a local printer that we worked with for many years here in Cedar Rapids because we know this guy would do fantastic work,” McDonald explained. “We also really wanted very high production on it, and we knew we would get that, and we’d also be right here so we could talk to them and look at it [as it was set up for printing].”

The creation of 2184½ was a herculean task, but Jackson and McDonald left themselves room to create a sequel, and it is clear that they have some nascent ideas for the arc of a second book.

“What happens to a person, a good person, a hero, when we give them the weight of authority?” McDonald asks, noting that the novel’s protagonist has gone from rebel to leader over the course of 2184½. “What do they do? Do they succeed? Do they resist temptation? Do they become better or do they go bad? That’s always a great question to ask.”