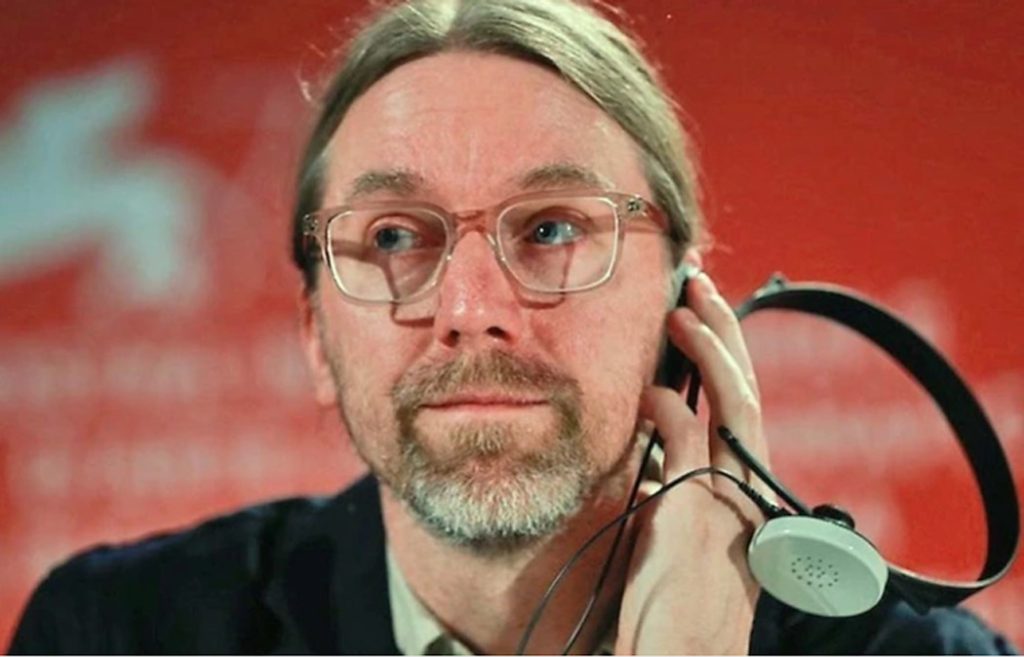

Screenwriter and producer David Kajganich, a 1990s graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, is excited to be back in Iowa City for the Iowa premiere of Bones and All on October 6 during FilmScene’s Refocus Film Festival. Bones and All was awarded two prizes at the 79th Venice Film Festival—Luca Guadagnino won the Silver Lion Award for Best Director and Taylor Russell won the Marcello Mastroianni Award for Best Young Actor for her performance as Maren Yearly, the lead character. The movie also stars Timothée Chalamet as her love interest. Billed as a coming-of-age, horror road-trip romance, Bones and All is an intriguing mix of genres, based on the Alex Award-winning book of the same name by Camille DeAngelis.

“We weren’t quite sure how this film was going to go over,” Kajganich says. “We’re all thrilled that people are responding to it the way that we hoped they would, which is as a love story, as opposed to a horror film. It’s both, but we hoped that the audience would be as, if not more, engaged with the love story—with a coming-of-age story element.”

Kajganich is excited to share the film with Iowa audiences, partly because “a portion of the film takes place in Iowa. It’s fun to bring it to one of the places where it was set.” He’s also looking forward to watching the film with “an off-the-street audience, because that is the audience the film was intended for.” He’s excited to “be able to listen and feel the energy of the crowd—to understand from a writer’s point of view, and a producer’s point of view, what works for this particular audience, and what doesn’t.” Kajganich says he “always learns an enormous amount from watching films that I’ve written or produced” with an audience, with “a bunch of people who like movies.”

Serendipity initially brought the Bones and All screenwriting project to Kajganich’s attention. He got an email “out of the blue” from producer Theresa Park, whom he’d never met. Park had recently optioned the book and thought he was a perfect fit. “When someone seeks me out specifically, I always take that seriously. I never take it for granted,” Kajganich explains. After reading Bones and All, he was “really intrigued by the book.” He “thought the book posed so many interesting questions and had intriguing characters,” but, because it was essentially the coming of age story of a young woman, he worried about being the right scriptwriter for the project. He called Park back, asking, “Are you sure the author wouldn’t prefer a woman write the screenplay, or at least have that option?” Park was happy to put him in touch with DeAngelis, and they clicked.

“We had a really great conversation about the book; about how I would adapt it, and thematically what I thought was at stake. It was just a wonderful conversation. So I got the author’s blessing to proceed.”

He felt the whole enterprise, bringing a YA book with a dark fairytale vibe that mixed three very different genres to the screen would be incredibly interesting. He knew the cinematic tone would have to change to “a hard R sort of drama,” adding “I hadn’t written anything like this before. I couldn’t say no. It was certainly not an opportunity I was going to turn down.”

Kajganich has extensive experience in adapting screenplays, and credits the Iowa Writers’ Workshop with giving him the training and courage to embrace the direction his career took. “I had trained in fiction writing here at the Workshop. I had both the academic training and the courage to take a book apart, and to be able to talk about it on several different levels independently from another: thematically, dramatically, and understanding how something that exists in a textual medium has to transition to a visual medium when it’s adapted for film.” He was able to go into meetings early in his career about possible adaptation jobs “with a real sense of confidence,” since he understood “how to take a book apart dramatically, while keeping it intact thematically, as one hopes to do in a good film adaptation of a book.” Kajganich thinks that his Iowa Workshop training, as well as the confidence of being an avid reader of books, gave him a fairly unique set of skills, which enabled him to land quite a number of adaptation jobs early on.

Kajganich loves the process of adaptation. “Personally, I think there’s something wonderful about recalibrating an existing story,” he explains. Either “taking a story that was written decades or more ago, and finding a kind of pulse to it that speaks to something that’s in the zeitgeist now, or taking a contemporary novel and understanding how to tell the same story visually, there are just such intriguing possibilities for having something that harmonizes with the original material, but has a kind of identity of its own.”

When he talks to the authors of the original work, he lets them know “I’m going to do my best to preserve the soul of whatever it is I’m adapting, but that I will probably have to break some bones.” Because cinema is a different medium than literature, a cinematic adaptation has to be told in different ways than the original material, which involves change. This can be both exciting and unnerving for an author to deal with. “I try to earn their trust,” Kajganich says. “And then, when I have a really good draft finished, that I’m ready to share, I want to prove that their trust was well placed.” There has to be a balance between honoring the author’s concerns and telling the story as the new medium dictates. He tries to limit author interaction to initial conversations where the trajectory is set, explaining that having an ongoing, creative negotiation with an author while writing a screenplay bogs things down. “I’ve been very lucky,” he says. “Every time I’ve done this, it’s turned out well. I have plenty of friends who write adaptations that have more hair-raising stories than I do.”

Kajganich is looking forward to the Q&A that he and DeAngelis will have after the opening night showing, precisely because the experience they had on this project “was a very good one.” He says “she’s very happy with the film,” adding, “I don’t know how common it is that an author would be willing to get up on a stage with a screenwriter who adapted her work and actually have a conversation about what a lovely experience it was.” Kajganich feels that the fact that he “listened to what she really needed a film adaptation of this book to include, in terms of its worldview,” played a major part. “It’s just a good example of how this kind of process can work in a world that’s full of nightmare stories about how it didn’t work for a lot of other films.”

Kajganich feels the focus of the Festival is providing a special opportunity for creatives across various disciplines to cross-pollinate, to enrich each other with different perspectives and approaches. “When I heard that the Refocus Festival was specifically geared toward adaptation and a number of definitions of that word, I was so excited. Obviously, I’ve spent a lot of my career thinking about this subject, but it just seems to me that these disciplines are often kind of siloed and don’t communicate very often.”

Kajganich says when he was a student at the Workshop in the mid-90s, “none of us wanted to be screenwriters or television writers. It was almost as if that point of view about narrative was somehow less interesting. Obviously, television has gone through a pretty miraculous revolution. Now, some of the best American literature happening at the moment is happening on television.” Kajganich thinks the disciplines of fiction, nonfiction, and playwriting are now open for cross-genre cross-pollination. And he thinks “it makes total sense that Iowa City would be at the forefront of having a festival centered around adaptation—not just the literal idea that books get made into movies, but because these different disciplines actually have a lot to say to one another.”

In terms of cross-pollination, Kajganich feels his perspectives on writing for a visual medium could “be really interesting to a memoirist” who hadn’t thought of their work in a visual way. And a novel writer could remind a screenwriter “that structure doesn’t have to be simplistic; there’s a sort of an urgency and complexity to text that sometimes screenwriters forget is an option.” Additionally, “there is a kind of heightened verisimilitude to film that writers and other mediums can sometimes forget is possible for them.”

Kajganich looks forward to an interesting creative and intellectual interplay, as people from different disciplines complement one another’s understanding. He adds, “I think about the conversation a screenwriter might be able to have with a poet, because poetry, even though that’s still a textual medium, is more attuned to the primacy of image. It would be fascinating to get a screenwriter and a poet together to talk about how narrative can operate through a language of the senses. I welcome the chance to have those kinds of constructive conversations where we all have slightly different terminology, toolbox, and attitude about what narrative can be.”

Kajganich has experience with constructive partnerships involving similar yet disparate approaches—Bones and All is the third film he’s worked on with director Luca Guadagnino. “We were lucky to find one another,” Kajganich says. “I don’t know that there are many teams of directors and screenwriters working together like Luca and I do.” While this sort of creative partnership happened often in the 1960s and ’70s, it doesn’t seem to happen as much anymore. Kajganich says that at the beginning of a project, he and “Luca talk for a solid month . . every day . . about every aspect of the script.” They talk about the visual language, thematically what the aim is, the nuance of every character and setting, and then Kajganich writes the script, fully understanding Guadagnino’s vision, while Guadagnino fully understood Kajganich’s vision. Which leads to a much smoother process of creative realization as the project coalesces. Kajganich says most of the revisions happen after the film is cast. “I will sit down with each actor, go through the scripts, and get the actors point of view about their arc, and their relationships with the other characters. Through those conversations, we will tweak and revise in order to make the part more organic to the way an actor wants to play the part. But it’s pretty rare that Luca will come to me after I’d written the first draft of the script with some kind of pivot. It just doesn’t happen because we front-loaded it all.”

Kajganich says he enjoys when the process of writing a screenplay becomes an ongoing conversation that’s reflected in the final product. “It doesn’t need to be reconceived,” he says.

Buy tickets at Refocus Film Festival.