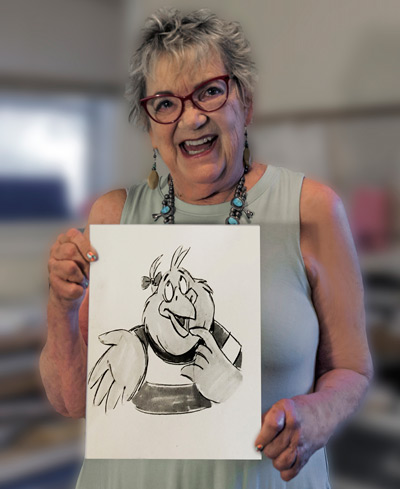

Bonita Versh was among the first women working in Hollywood’s animation industry, and her career took off during the animation heyday of the 1960s and ’70s. Now living in Fairfield, Versh will be giving a presentation about her experiences working in a male-dominated field on Saturday, July 16, 1:30 p.m., at the Fairfield Public Library. Joining Versh will be her longtime friend and fellow animator, Joanna Romersa, who is visiting from the West Coast. They’ll give a rundown of the animation process, share anecdotes about working in Hollywood during the golden era of animation, and offer advice for those interested in pursuing an animation career.

“Basically, all my life I’ve loved to draw,” Versh says. “Life drawing, which I majored in, just happens to be the prerequisite for a great animation career.” A graduate of the University of Wisconsin, Versh’s first job was in the paint and ink department at Hanna-Barbera. An animation studio and production company founded in 1957 by Tom and Jerry creators William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, Hanna-Barbera produced popular shows such as The Flintstones, Johnny Quest, The Smurfs, and Scooby-Doo. Hanna-Barbera allowed women more advancement opportunities, according to Versh, and “was working with the best artists in town.”

Versh joined the company in 1968. Joanna Romersa started with Hanna-Barbera in 1963. “I was working in layout,” says Versh, “and Joanna was supervisor for the assistant animation department, and we met one day at the Xerox machine. We started talking and laughing, and we couldn’t stop laughing. We decided we would be friends after that.”

Romersa’s 63-year career began in 1954. She started working for Disney in Burbank, California, before she’d finished college. “I had little to no real interest in cartoons,” Romersa says, “but the opportunity to learn the art of inking, be paid $42 a week—excellent pay back then—and work in a Hollywood studio was too exciting to turn down.” She promised her mother she’d go back to college after working for a year, but she met her future husband, Tom Romersa, three months later, so she continued to work on the feature films Lady and the Tramp and Sleeping Beauty.

In those days, Romersa says, Disney did not allow women to be trained in the actual drawing process of animation, so her career could not advance. After working briefly in the checking department, she quit and started working for a paint and ink studio that made television commercials. Then, in 1963, Romersa started at Hanna-Barbera as an inker. “It was a totally different experience,” she says.

Versh explains that inking and painting animation cels “was one of the last jobs of a long series of steps that put art to film.” Hanna-Barbera was a great place to learn the ropes, she says, noting that the company “was a well-oiled factory of animation, churning out 10 to 13 half-hour shows a week for Saturday morning cartoons.” Versh is grateful that the job allowed her to spend ten years getting a full education on “how to make animation from start to finish, and getting paid for it.”

Versh spent a large portion of her career as a freelancer. Once she and her husband had a daughter, freelancing allowed her to balance work and parenting.

According to Romersa, it was common practice for Hanna-Barbera to lay off animators every November, and rehire them the next year in February or March, “when a new season of Saturday morning cartoons was ready to be inked.” During the interim, Romersa worked for boutique studios such as Kenny-Wolf Productions and took animation classes. In 1971, working as an assistant animator at Hanna-Barbera, she was told she could become a full-fledged animator if she assisted Hugh Fraser, a talented former Disney animator who was challenging to work with, because he “left a lot to be done on a scene.”

Versh explains that assistant animators ended up doing most of the work. “I was such a good assistant animator to the men animators, they didn’t want to give me up. Basically, they just did a few drawings, and I had to fill it all in, which is what the assistant does. You draw all the drawings in between, and then you clean it up and you make it really beautiful.”

Eventually, Versh and Romersa both attained animator status, holding their own in a male-dominated field. But it wasn’t always easy, Versh says. Career advancement required being vocal and refusing to be eclipsed by new male talent who hadn’t yet put in the work. “I had to fight for my job,” she says. “It was very hard for me, as a woman, to be assertive, and to be competitive. But my art stood for itself. I was good. I was fast. And I could do all the different jobs, thanks to my various freelance work.”

Freelancing at different companies and working under some really good directors allowed Versh to learn all the skills a successful director needs to know, and she became one of the first female commercial directors.

Romersa supervised Hanna-Barbera’s assistant animation department for several years before becoming supervisor of the animation department and then director. She later worked as supervisor of timing direction at both Fox and Disney. Timing directors decide how a character moves and how long that movement continues, taking into account the tone of the animation as well as the character’s physical traits. Animators base their drawings on this input. In her next career move, Romersa became the animation director at Disney before retiring in 2017.

Versh also worked for a number of boutique studios, and spent the last decades of her career working for Klasky Csupo, the studio behind many of Nickelodeon’s most popular series, including Rugrats, The Wild Thornberrys, and As Told by Ginger.

In the 1980s, animation production started to move overseas, and jobs often became international adventures. Versh traveled to China, Paris, and Germany for animation projects. Versh feels lucky she was working more in the commercial side of the business, as animated commercials continued to be produced stateside.

In 1995, Versh was involved in the creation of Women in Animation, a non-profit organization founded to support and promote female animators. WIA is still active today, and helps train and mentor young female artists, providing skill seminars, panel discussions, scholarships, and business networking. Versh is also proud of being instrumental in the founding of the Vancouver Institute of Media Arts in British Columbia. She convinced one of her late mentors, renowned animator and director Lee Mishkin, to become the first dean of animation. Mishkin created the animation curriculum and Versh taught summer classes for many years.

Both Versh and Romersa remember a lot of camaraderie and support in the animation community. “When I recall those crazy times when we worked so hard and had so much fun, I am so grateful that I was a part of it all,” Romersa says. “The rooms were full of sunshine, we drew cartoons of our friends, played harmless tricks and jokes on everyone, and laughed a lot! I treasure those wonderful friends and memories of days in the golden age of animation.”

Despite retirement, Versh and Romersa continue to be involved in art and animation. “Besides all of my animation art, my personal art is my joy,” Versh says. Versh recently created animation for the Honey Wars sequence in Heroes of Fairfield by local filmmaker Dick DeAngelis, and Romersa is still active as a producer.