Mark Twain, the pen name of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, was born in November 1835, coincident with the arrival of Haley’s Comet. That spectacular event occurs about every 75 years, and in April 1910, as Clemens was on his deathbed, he and the comet crossed paths again.

At the moment of Clemens’s death, among those at his bedside was Albert Bigelow Paine. A prominent writer and a close associate of Clemens, Paine had been chosen to write his biography and to serve as his literary executor.

Three months later, a newspaper in Keokuk, Iowa, reported that Paine had been in town, gathering information for his biography of Clemens. “It is not generally known,” the article said, “that the first literary efforts of Mark Twain were for a Keokuk paper. He worked with his brother in a printing shop on Third Street.”

What the article failed to mention is that Paine himself had Iowa roots. During the American Civil War, Paine and his parents had lived in Bentonsport, near Keosauqua, on the Des Moines River, in the southeast region of the state. His father, Captain Samuel Estabrook Paine, was a Union officer, and the first commander of Company I of the 19th Iowa Infantry.

The elder Paine had led his unit in Arkansas in the Battle of Prairie Grove, on December 7, 1862, about ten miles from Fayetteville. Captain Paine was wounded that day, and was discharged the following year, because of disabilities. At the time of the battle, his son was still an infant. After the father returned home to Iowa, the family moved to Xenia, Illinois, where young Albert attended school, and where their historic home still stands.

During his life as a writer, Albert Bigelow Paine not only authored a five-volume biography of Mark Twain, he published four other books about him, including his letters and speeches. He also wrote other biographies, children’s books, novels, travel books, and books of poetry, including humorous verse. And he was a member of the Pulitzer Prize Committee.

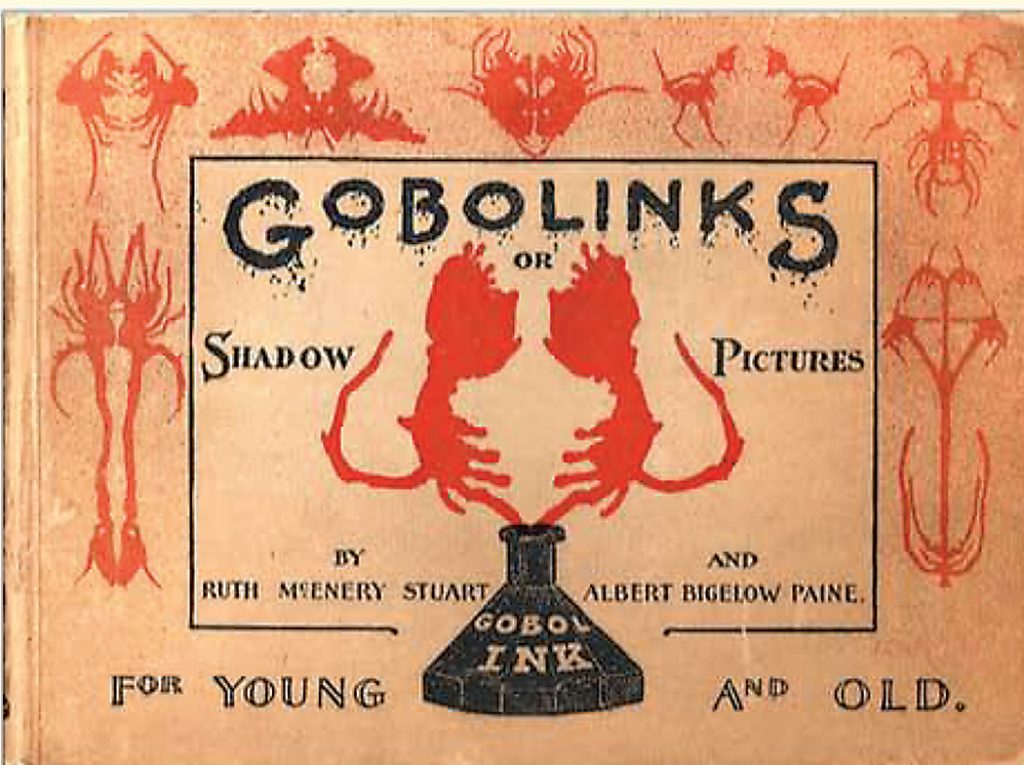

Paine’s most unusual achievement may be his co-authorship, with Ruth McEnery Stuart, of a book of “klecksographic images”—which are pictures made from inkblots—juxtaposed with humorous verse. The book’s title, Gobolinks or Shadow-Pictures for Young and Old (1896), is a merger by portmanteau of “goblin” and “ink.” On the cover is a bottle of ink that bears the label Gobol Ink.

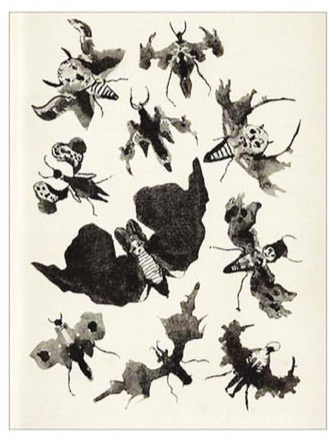

The German word for an inkblot is klecks. In the latter half of the 19th century, it was a source of amusement to drop ink on a scrap of paper, then fold the paper to produce a bilaterally symmetrical “picture.” If this at once reminds you of the famous Rorschach Inkblot Test developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach, you are precisely on target. This pasttime had been commonplace during Rorschach’s childhood, and he was preoccupied with it—so much so that his classmates called him Klex (or inkblot).

Years earlier, a German doctor named Justinus Kerner had used comparable inkblots to inspire a book of poems. French psychologist Alfred Binet, who devised the IQ test, was also fascinated by inkblots, as was the writer Victor Hugo, who made thousands of “accidental” images, combining chimerical inkblots with coffee stains, wine, and soot.

Paine and Stuart surely must have been aware of some of these earlier experiments. At one point there was even a popular game called Klexographie or Blotto. When they produced their book in 1896, Paine and Stuart shared a procedure which also could be a game. Each player had a limited time in which to make a “gobolink,” using ink and folded paper, and then write a verse to go with it.

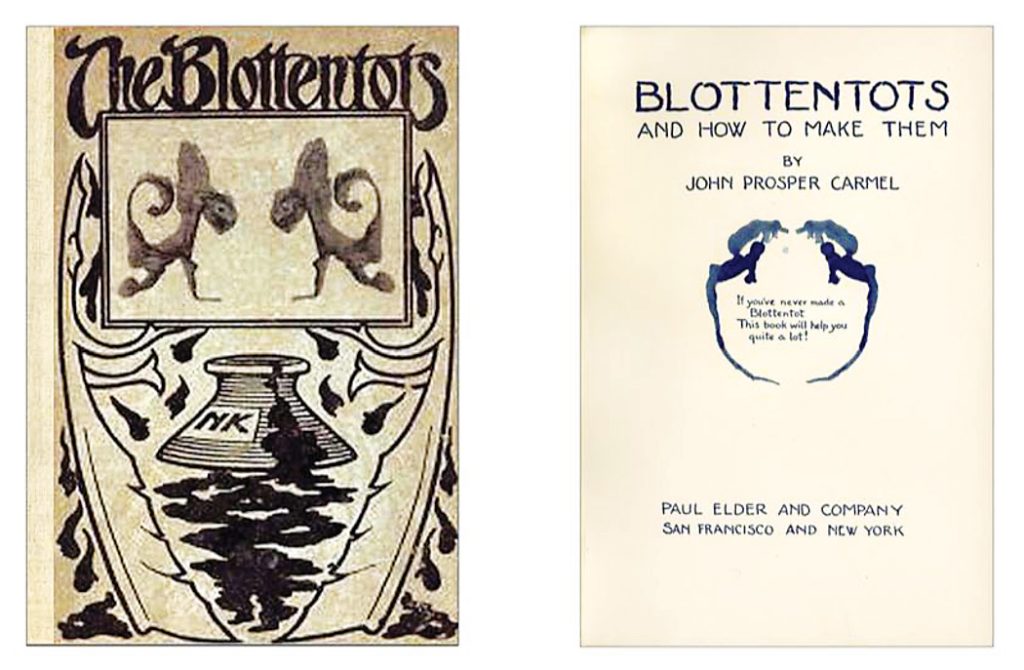

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, the coauthors must have been swollen with pride when just 11 years after the release of Gobolinks, an author named John Prosper Carmel produced a disarmingly similar book (albeit not as good as theirs) of inkblot images and poems, titled Blottentots, and How to Make Them.

The book’s hand lettering is attributed to a book illustrator named Raymond Carter, and there is speculation that Carmel was his pseudonym. Carmel’s book was warmly received by reviewers, as in Goodwin’s Weekly, where it was described as “a whole menagerie” of “startling, ludicrous, haphazard, jackadandies—the funniest that ever jumped out of paper—a jolly jingle with each, and full instructions in rhyme for making others just as funny.”

The instructions in Carmel’s book, unlike Paine and Stuart’s, are themselves jolly jingles, as in this example:

Don’t crease exactly at the blot—

You’ll have a fearful muddle;

Press gently, too, and not a lot,

Unless you want a puddle.

For the moment, we need to go back to Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain’s biographer and the coauthor of Gobolinks. From all that has been said thus far, it seems he led a virtuous life that was free of any behavioral taints.

It is with some regret to note that a 2018 article in the Mark Twain Journal reports otherwise. In “Biographer Obscura: The Secret Life of Albert Bigelow Paine,” the article’s author, Max McCoy, documents his discovery that Paine may have been a bigamist—that he married twice, that he wed his second wife (the daughter of his dentist) without having divorced the first, that he fathered one daughter by his first wife and two daughters by the second, and that none of the children were told of their father’s bilateral wives. They had not so much as an inkling.

Note: Both Gobolinks and Bottentots are in public domain, and can be accessed and downloaded online.

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, designer, and emeritus professor. Of late, he has been producing online video talks about subjects related to art, design, and camouflage, including one about hidden pictures (such as pictorial inkblots).