For those who believe, no proof is necessary. For those who don’t believe, no proof is possible.

Whether you believe in near-death experiences or not, NDEs are reported worldwide by people of all ages who were revived medically, or by chance, from clinical death. And since the emergence of resuscitation in the 1960s, and the 1975 publication of Raymond Moody’s Life After Life, reports of NDEs have surged. But are these experiences real or imagined? Or are they just some hallucinatory aftermath as the brain shuts down? As the Netflix series Surviving Death suggests . . . it depends on who you ask.

Survivors report that near-death feels more real than life in the body. And that it alters life for the better—with the possible exception of survivors whose friends and family refuse to believe them. That struggle gave rise to a profession of psychic therapists who counsel alienated survivors. Because those who return from death are no longer the same people. What they once believed is not what they know now.

And then there are scientists of all flavors who give no credence to anything they cannot measure or test. Which raises a question posed by this series: should our inability to quantify an event negate its existence? This, too, depends on who you ask.

Surviving Death is based on the 2017 book by investigative journalist Leslie Kean. Episode 1 introduces us to credentialed researchers, as well as survivors like orthopedic surgeon Mary Neal. When Mary drowned in a kayaking accident, she perceived a vision of life beyond physical death. She experienced overwhelming calmness, a welcoming committee of heavenly beings, and a feeling of being more alive than ever, with no fear of death. “Death,” she says, “is not the final word. And it’s not the end.”

NDEs were formally recognized in 1892 by geologist Albert Heim. An accidental fall while mountain climbing delivered a surprising sense of calm instead of panic and pain. This prompted Heim to search for others with the same out-of-body experience, which led to a formalized study.

Fast forward 1967: Dr. Ian Stevenson at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine founded the Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), a research mecca for scientists and physicians to study survivors of clinical death with a story to tell.

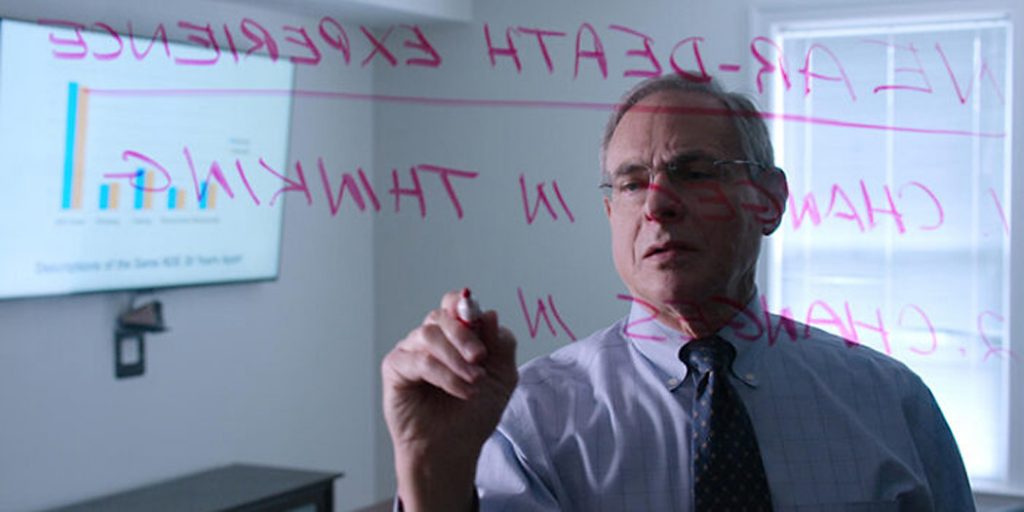

DOPS research attracted medical doctors like Bruce Greyson, M.D., Chester F. Carlson Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, whose specialties include death-bed visions, and neuropsychiatrist Peter Fenwick from University of Cambridge, who became curious when a patient described an NDE after Fenwick resuscitated him. Fenwick, who claims he used to think that NDEs were an American phenomenon that the British were far too sensible to experience, pursued NDE research for the next 40 years.

By far, the most memorable accounts are from episode 6, in which young children recall past lives. (Although it occurs to me . . . if their memories are real, we would not only have to consider that we all live more than once, we would also have to accept that we learned it from three-year-olds.)

So how on earth do toddlers remember previous lives? There are theories afloat that certain perceptions and memories will surface in the earliest years of life if children have the confidence to honor them. The fortunate offspring in episode 6 have supportive, open-minded parents. And even if they don’t understand their children’s mysterious memories, which can involve sentiment, grief, or even trauma, they try to acknowledge them.

Plenty of moments will stick with you. Like three-year-old Atlas, who remembers his name from his previous life, the name of his previous mother, and where they lived. On a visit to Dr. Jim Tucker, DOPS specialist in past-life research, Dr. Tucker shows Atlas a wide mix of photos, including some that he located according to Atlas’s recollections. Atlas instantly identifies the correct pictures from his former life—his mom, his dad, his house, and his neighborhood playground.

And then there’s James Leininger, who recalls his WWII fighter pilot mission in Iwo Jima, a story that boggles the mind. Young James’s recall of names and places, and his intimate familiarity with military aircraft, convinced his parents to do some research. Good luck getting through this segment without feeling wowed and weepy.

The first and last episodes of Surviving Death are highly recommended. Episode 1 covers survivors and researchers; episode 6 visits the past through the memories of children. All the good stuff. And then there are episodes 2 through 5 that change the texture of the series and dim the light. They’re about mediums who communicate with the dead or the spirit world. However noble the intention of this exercise, it feels dark to me. But to each their own.

So . . . what is the upshot here? And what should we believe? Whatever your conclusion, Surviving Death makes an impressive case through an intelligent presentation. Whether “survival” is imagined or true, these two fine episodes deliver an educational odyssey without a whiff of “crazy.” Go ahead. You be the judge.