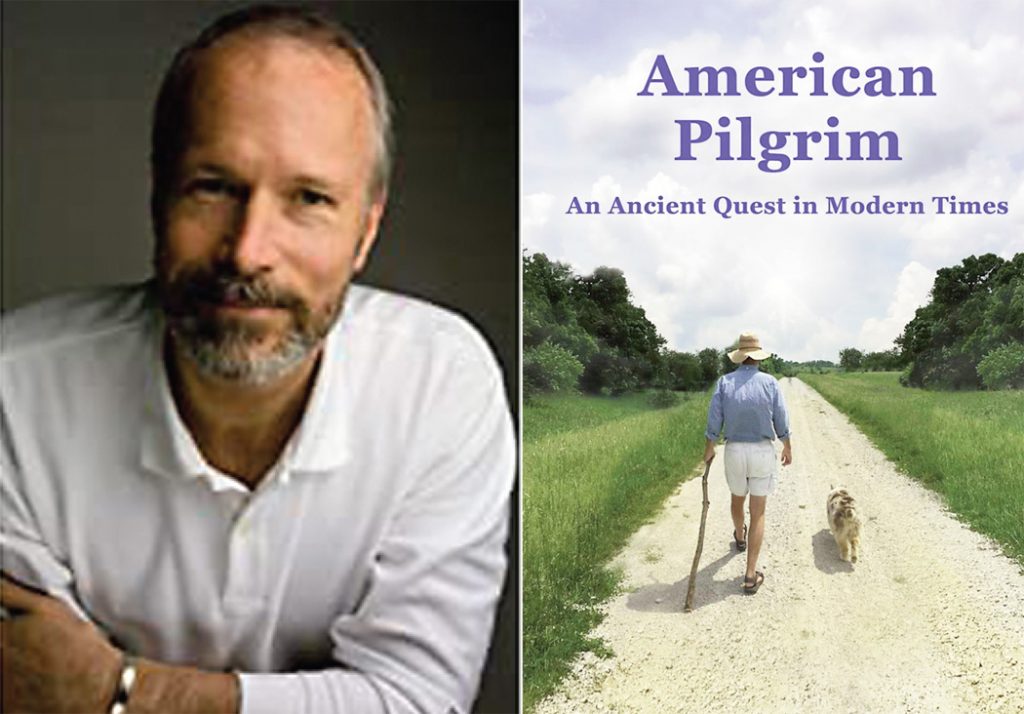

Bart Walton’s life and ongoing pursuit of enlightenment has taken him all around the world—including to his current residence in Fairfield, Iowa. In his self-published memoir, American Pilgrim: An Ancient Quest in Modern Times, he reflects on his journey and highlights some of the important ideas and individuals, cultural moments and movements, and personal decisions and detours that have shaped it.

Walton is an amiable companion with a direct, friendly, readable style. That style conflicts slightly with his decision to provide endnotes to each chapter, many of which cite Wikipedia as his primary source. Still, the notes speak to the balance he is trying to strike: a personal story in the context of a philosophical framework that may be unfamiliar to many readers.

Walton answered questions about his life, book, and publishing process via email.

Was there a specific moment or a series of events that sparked your desire to write a memoir?

During the 1960s two unusual events converged on post-war America. First was the advent of the psychedelic experience, facilitated by hallucinogenic drugs. Second was the arrival of Hindu and Buddhist teachers, bringing their spiritual teachings and practices from the Far East. The impact of these events triggered a wave of spiritual seeking that spread across North America and into Europe. Like many young people who were swept up in these events, I embarked on a spiritual quest that took me to nearly every continent over 50 years and continues to this day.

A few years ago, it occurred to me that very little had been written about these events. People born after 1975 know almost nothing about them, or perhaps they’ve heard bits and pieces from their parents or grandparents. I realized that my life is a thread in this history and the best way to document what happened would be for me to tell my own story. With these thoughts in mind, I decided to write a memoir of my spiritual journey within the social and historical context of the 1960s and ’70s.

There’s a tension in the book—particularly in the early part—between the idea that various drug experiences opened your mind to new possibilities and the idea that some of those experiences had less than beneficial consequences. As you were writing, how did you think about these tensions?

Perhaps the underlying question is whether I personally recommend the use of psychedelic drugs as an aid in the spiritual quest. The short answer is no. Psychedelic drugs, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline, are powerful substances. During the ’60s and ’70s, people used these drugs indiscriminately. As a result, there were quite a few casualties along the way. If a person feels drawn to this experience, I recommend they work with a professional therapist who is trained in the use of these drugs. Under professional supervision, they can be useful for some people in certain circumstances.

Looking back, I’m grateful for my psychedelic experiences. Without them, I’m not sure I would have been drawn to meditation, which became an indispensable tool on the spiritual path. However, as I said in the book, overuse of these substances can be harmful. In this sense, I feel lucky that I didn’t do any long-term damage to my nervous system. Eventually, I had to face the fact that genuine spiritual growth requires more from me than simply taking a pill.

Throughout the book you offer quite a lot of history behind the topics and practices you focus on while also sharing details of your life. Was it difficult to find a balance between these things? How do you think the background content works with the personal content to create the narrative?

In recalling my story, I wanted to take the reader with me on a journey. To do this, I felt the need to include some background and context, especially with respect to people, places, and ideas that might not be familiar to the reader. As you said, it’s a question of balance. Without enough historical background, the reader might feel lost in a maze of unfamiliar words and ideas. But with too much background, the personal story might get obscured and end up reading like a travelogue.

Tell me about your decision to self-publish. Did you always intend to go the indie route or did you shop this book—and your other book, A Dose of Common Sense: Guide to Complementary Self-Care After 50—around first?

In the beginning, I tried to find a publisher. A dear friend and fellow author introduced me to his publisher in London, who at first seemed interested. After weeks of back and forth, he finally declined, saying the book wasn’t a good fit for his company. I then spoke with other authors and even met with a literary agent. At some point, it became clear that no matter how good a book is, publishers are simply not interested in authors who don’t have a large following. Once this reality sunk in, I abandoned the idea of finding a publisher and decided to go it alone. The next step was to find a professional editor and book designer. After a couple of false starts, I was fortunate to find two talented individuals who helped me transform the manuscript into a nicely finished book.

Your life has unfurled in many different places, so I’m wondering to what degree you think of yourself as an Iowa writer.

I was born and raised in Kentucky and only migrated to Iowa somewhat recently. But like Iowans, people in Kentucky are plainspoken and don’t carry around much in the way of attitude. I’m told that my writing style reflects this trait—spare, straightforward, and to the point. So in this sense, I feel right at home among Iowans and look forward to sharing my writing with them. Also, since Maharishi and TM were both central to my story, many Iowans might like to know more about the meditation practice that eventually landed in Fairfield as Maharishi International University.

After all these years of seeking enlightenment, do you still believe in the search?

Yes, very much so. Who am I? Why am I here? What happens after death? These questions don’t belong to any particular group or system of belief. They arise spontaneously out of our human nature.

In the beginning I thought of enlightenment as a spiritual destination or final attainment. Now this notion seems a little naive and misleading. Over the years, I’ve come to view enlightenment as a shift in our identity as both physical and spiritual beings. As the philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. Rather, we are spiritual beings having a human experience.”