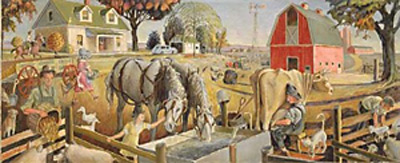

American astronaut Peggy Whitson was born in south central Iowa, in Ringgold County, and attended high school in Mount Ayr, the county seat. She is that region’s claim to fame, although it should also be noted that the parents of Abstract Expressionist artist Jackson Pollock also grew up in that county. My favorite feather in the cap of Ringgold County is a Depression-era WPA mural that hangs in the U.S. Post Office in Mount Ayr. Created in 1941 by local artist Orr Cleveland Fisher (1885–1974), it is titled The Corn Parade. I have admired it for years, but until recently, I had only seen reproductions.

I drove down to Mount Ayr a few years ago, walked into the post office, and was delighted to see the mural firsthand in all its glory. It is installed in the lobby, above the postmaster’s office door. I photographed it from a low angle, without a ladder, which of course distorted the overall shape. But I was able to straighten it later and restore its true proportion, using appropriate software.

Older readers may already know about the WPA. It dates from the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt created government subsidy programs to stabilize the economy by hiring the unemployed to work on public projects. The acronym WPA stood for the Works Progress Administration, an agency that oversaw several arts-based programs, including the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP).

In Iowa, the PWAP regional director was Grant Wood. It was he who approved the artists who were commissioned by the government (at a salary of $26.50 to $42.50 per week) to create public murals, mostly for post office lobbies. As many as 35 were commissioned for Iowa buildings, including two by Orr Fisher (in Mount Ayr and Forest City).

The majority of those in Iowa have survived, although in a few cases they have been relocated to libraries or city halls. Fisher completed his Mount Ayr mural nearly 80 years ago, and Ringgold County is fortunate that it still hangs on the wall it was made for. If you haven’t seen it, you should make the pilgrimage.

The Corn Parade is utterly charming and funny. It is a colorful, cartoon daydream of a harvest parade in an Iowa farming community. Its central feature is a float being towed by a tractor. Walking alongside are a trained pig and a marching clown, followed by an unbelievably tall Uncle Sam on stilts.

On a wagon on the float is a gigantic ear of corn, like those huge Paul Bunyan vegetables on humorous vintage postcards. On top of the corn is a platform for three musicians, who are following the raised baton of an eccentric-looking band leader. An ear of corn as massive as this must surely have resulted from a record-breaking corn harvest. Now that is something to crow about, a rooster on the corn proclaims, and a billboard on the right contends that “CORN IS KING.”

When asked about the mural, Fisher replied that some of its characters were based on actual residents of Ringgold County. For example, one of the figures is the Mount Ayr postmaster, above whose door the mural would hang. The mayor of the city is mounted on a horse on the left, and the photographer, tractor driver, and others were also local citizens.

The Corn Parade is not an easel painting, but a large wall mural that measures 11 feet wide by 5 feet high. Fisher had twice studied briefly with the French Academy-trained Iowa artist Charles A. Cumming at his Cumming School of Art in Des Moines. Other than that, Fisher was self-taught, or learned through correspondence schools. He recalled that from an early age, he was preoccupied with drawing, an interest that never abated. As he put it, “everywhere I have gone I have drawn. I have drawn almost everything imaginable . . . except a salary.”

He had a lifelong interest in illustration, design, and cartooning, and he especially admired the drawings of Ding Darling, the celebrated Des Moines Register editorial cartoonist.

In every square inch, there is a whimsical energy in The Corn Parade. As restless as a rolling stone, the zany mural reflects the zigzag paths in Fisher’s life. After flunking Latin and German at Drake University in his early 20s, he “quit school and went West.”

In Wyoming, as he later recalled, he “got work on a ranch . . . organized a Sunday School; drove an eight-horse freight team with one line 90 miles across the desert; slept on the ground and in a covered wagon when 40 degrees below zero; heard the coyotes howl; road a fourhorse load of pine logs down the mountain behind a run-away team, but escaped with only bruises; fell through the ice riding a horse across a mountain stream, jumped to solid ice and escaped, but the horse chilled to death; bet Uncle Sam that I could live on a quarter section of land, and I won the bet; built a log cabin, hunted deer and elk and really ate bear meat.”

He was also an erstwhile inventor, and at age 19 he received a U.S. Patent (No. 759,257) for an Automatic Whistle Operating Mechanism for locomotives. Later, having returned to Iowa from his adventures in the West, he worked as an electrical signalman for the railroad, made illustrations and cartoons for signalman publications, and worked as an advertising artist for a farm implement company in Waterloo, Iowa. But after a while, he gave that up and once again headed west.

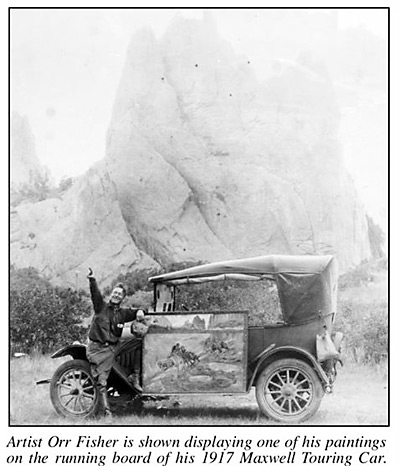

He toured scenic vistas in “Max” (a 1917 Maxwell Touring Car in which he camped), painting landscapes en plein air. He made comical get-well-soon postcards that were sold in hospital gift shops. He also spent some time out east, where he built a studio and joined the artists’ colony at Woodstock, New York.

In the last phase of his life, he went west a final time, settled in California, and died in 1974 in Fresno. In retrospect, Orr Fisher led his life as a kind of parade. He was a free spirit, always in motion—and marching to a drummer that only he could hear.

Roy R. Behrens is emeritus professor and distinguished scholar at the University of Northern Iowa. For more on Orr Fisher, see Ringgold County Archives.