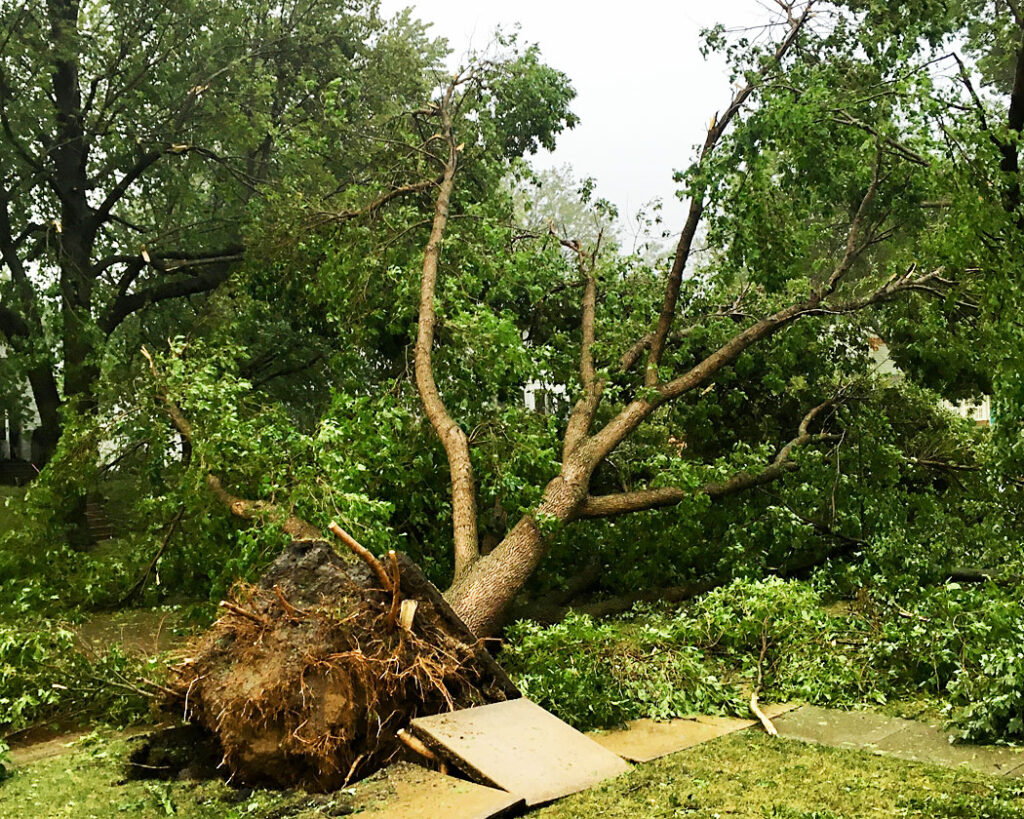

A howling came through my city, and it was unlike anything I’d ever seen.

In Cedar Rapids, everyone is now intimately familiar with a derecho. The storm visited town on a Monday, bringing hurricane-force winds and leaving devastation as a parting gift. A couple hundred thousand without power. Many without a home. Many more without a sense of what could come next. My city has experienced this before.

The 2008 flood came with similar rapidity and destruction: 1,126 city blocks were flooded, ravaging core neighborhoods and gutting any idea of normalcy. It tried our souls, but we rebuilt and returned better. Now, we face our second large-scale natural disaster within the span of 12 years. At times, it seems if not for bad luck, CR would have no luck at all.

• • •

When one is born and raised in Cedar Rapids, they fall into one of three camps:

1. Those who know nothing better for their needs and find comfort in the practical aspects: relative safety, consistent convenience, and affordable real estate. These are CR’s lifers.

2. Those who know something better, pine for it, and flee from this place as soon as physically possible. These are CR’s departed.

3. Those who know of something more alluring, also pine for it, but realize that this city is themselves—an intrinsic identity that can’t be outrun or fled from. These are CR’s conflicted.

I was born in Cedar Rapids. I was raised in Cedar Rapids. And I decided to invest in Cedar Rapids, buying a home in the Oakhill Jackson neighborhood in 2012. I am Cedar Rapids—and I find myself wincing even as I write it.

Why?

Because to be Cedar Rapids is to ostensibly be nothing. In the Midwest, I’m too big and too urban to wrap myself in the farmer mystique—a city slicker in the middle of an agrarian state. But I’m also too small to mean anything to the rest of the world—a country hick or a complete mystery.

All of the above seemed amplified after the derecho. The national news has largely overlooked or ignored our disaster, and when it has been covered, the focus has been more on downed cornfields and flattened farms. The agrarian destruction fit the narrative; the urban devastation in a city with a metro population of 250,000 didn’t.

In the aftermath of the storm, without power, I found myself grasping in the dark (literally and figuratively) for answers, for hope, for my toothbrush. I’m even writing this in the dark as a note on my phone, going on my seventh day without power.

Life lived as a Cedar Rapidian has found me grasping in a similar way: for self, for identity, for how to define my love for a place I often also disdain for its seeming inability to stand out and represent something more.

• • •

About an hour after the storm passed, our neighborhood was out in force to assess damage and start the cleanup. An elderly woman who lives alone soon had a team of neighbors cutting branches from a downed tree in her yard and hauling it to the curb. A family from Africa that had moved in only a few months prior was the first to start to work. They were followed by a half dozen other people. Within two hours, to look at our backyards, you hardly would have known a disaster took place. This scene has repeated itself numerous times in neighborhoods across the city.

I can’t say the derecho has reconciled my feelings for my city, but it has strengthened my pride in its attributes: its resilience, its sufficiency, its aversion to self pity. And perhaps the city has gained a distinctiveness from how it reacts in times of crisis. Cedar Rapids has come to embody human resilience.

The storm has also heightened my realization that I’m inseparable from my city. The poet William Carlos Williams, in describing his conception for his epic poem “Paterson,” said that, “a man in himself is a city, beginning, seeking, achieving, and concluding his life in ways which the various aspects of a city may embody . . . any city, all the details of which may be made to voice his most intimate convictions.” Williams went on to write that, “the city the man, an identity—it can’t be otherwise—an interpenetration, both ways.”

My identity derives from my city, and that identity manifests as resilience. I can leave this city, but it’s imparted something that will never leave me: a collection of clichés that actually function as fundamental truths. Without them—without my city—I’m rudderless, I’m nothing.

• • •

Let me tell you a story about yellow jackets. Yes, the flying (and stinging) insects. Yellow jackets have been harmonious neighbors on my back deck for years. They spend hours each day working at a feverish pace, hovering and collecting small amounts of the wood to construct their nest. It’s painstaking work that takes the entire summer to complete.

As I walked across my lawn after the storm, I noticed the yellow jackets’ nest was a casualty—destroyed by the onslaught of wind, flying debris, and fallen trees. Months of work destroyed in only a matter of minutes. The scattered remnants sat beside shingles and siding from nearby houses. I figured I’d seen the last of my yellow jackets for the year. But the next morning, under the brightness of a sunny day, I walked out back to see yellow jackets hard at work collecting wood to rebuild—a scene emblematic of a city that moves forward, because moving forward is its second nature, its identity.

Chad Cooper is a lifelong resident of Cedar Rapids and local copywriter.