The names of white suffragists who fought for women’s right to vote are unfamiliar to many people. The names of non-white suffragists are probably unknown to even more. During the 70-year campaign for women’s suffrage in the U.S., white and black suffragists worked well together some of the time. At other times, black activists were mistreated by their white peers.

On March 3, 1913, for example, thousands of women gathered in Washington, D.C., to support a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. Strategically, they held their massive parade in the Capitol one day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Sitting astride a stately white steed while clad in a white gown, white gloves, and a billowing white cape, lawyer and activist Inez Milholland Boissevain (a white woman) led a procession of 5,000 marchers, nine bands, 20 floats, and four mounted brigades.

Worried about alienating white Southern suffragists, parade organizer Alice Paul of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) relegated black marchers to the back of the parade. Some reports indicate that black activist Mary Church Terrell, a writer and educator from Memphis, Tennessee, marched there with 25 members of the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority from Howard University.

Journalist, newspaper editor, and activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a black woman born into slavery in Mississippi, refused to march in back. According to published reports, she explained, “I am not taking this stand because I personally wish for recognition. I am doing it for the future benefit of my whole race.” Wells-Barnett marched instead with the Illinois NAWSA delegation. (She had moved to Chicago after the office of the Memphis newspaper she co-owned was destroyed by outraged Tennesseans: in her newspaper’s pages she’d decried the lynching of three black grocers and championed African American rights.) Some reports indicate that in 1913 about 40 black women did manage to march with their state delegations or in professional groups to which they belonged.

Incidentally, although the parade started off well, partway through the event, men in the Capitol for the inauguration attacked the suffragists. Policemen stationed along the parade route failed to intervene, and 100 marchers had to be hospitalized. After a Congressional investigation, D.C.’s police superintendent lost his job. Despite the violence—maybe partly because of it—the 1913 parade increased support for women’s suffrage.

Carrie Chapman Catt, whose Winning Plan facilitated the suffragists’ success in 1920, has come under scrutiny for her attitude towards black activists. In 1921 Catt singled out 12 suffragists for a special honor. She had their names inscribed on bronze plaques that she affixed to stately trees growing on farmland she owned in Westchester County, New York. All the women Catt honored were white.

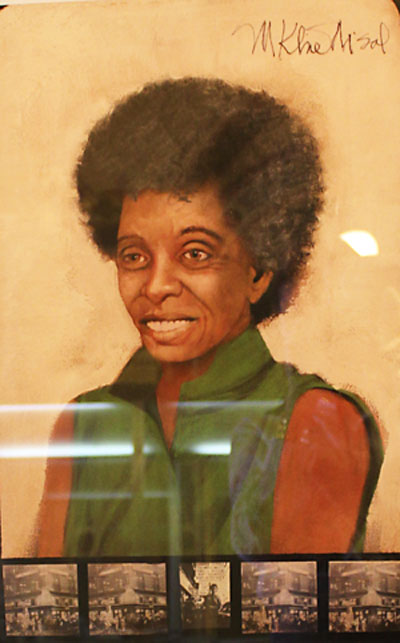

Present-day Iowa artist Mary Kline-Misol is honoring 19 suffragists by painting their portraits for her Battle for the Ballot: The Suffrage Project. Besides writing 19 brief biographies to accompany this exhibit, Kline-Misol incorporated historical photos into each woman’s portrait. Her paintings feature ten black women and nine white ones.

This year, the League of Women Voters of Iowa and its local chapters are honoring suffragists through a special campaign: Hard Won Not Done, A Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Ratification of the 19th Amendment from an Iowa Perspective. Dozens of projects are in the works. One championing the contributions of non-white women is titled Toward a Universal Suffrage: African American Women in Iowa and the Vote for All. The published goal of this project is “to tell the story of suffragist women in Iowa whose histories have been unwritten, overlooked, or written out of mainstream history.” Aided by partners, this project’s organizers will create a database that ensures that the stories of non-white suffragists are known to all Iowans. A traveling exhibit focusing on African American suffragists in Iowa will be created as well.