“Which one of you will hurt me?” —What the makeup artist tells the bachelorette to learn about the three bachelors competing to meet her on The Dating Game

Streaming on Netflix, Woman of the Hour tells the true story of Cheryl Bradshaw and her near miss encounter with 1970s serial killer Rodney Alcala on the TV episode of The Dating Game.

Texas born Rodrigo Jacques Alcala Buquor became known as the Dating Game Killer. His history includes a discharge from the Army following a nervous breakdown and suspicions of sexual misconduct. He was also diagnosed with antisocial personality syndrome, which prompts hostility, aggression, disregard for the law, and inability to feel guilt or remorse—though in the movie we are mystified by Alcala’s emotional crying spells. In the 1970s, when law enforcement gave lower priority to offenses against women (sadly, true), Alcala went unnoticed. These were the days before the internet and crime databases, which would have revealed his prison record and sex offenses. Eventually, Alcala was convicted for some of his crimes, but not until after his appearance on The Dating Game.

I was drawn to this film, despite its grim topic. Maybe because a murderer had the audacity to appear on a nationally viewed TV game show, masquerading as a charming, datable guy. Maybe because it was a reminder that we, as humans, are smart and resourceful yet deceivable. Who among us is not guilty of misjudgments of all shapes and sizes, more often than we’d like to remember? Fortunately, we’re also endowed with a detector that my husband refers to as radar. But first, for those of us who have never experienced the pleasure or the agony of viewing The Dating Game, here’s the rundown.

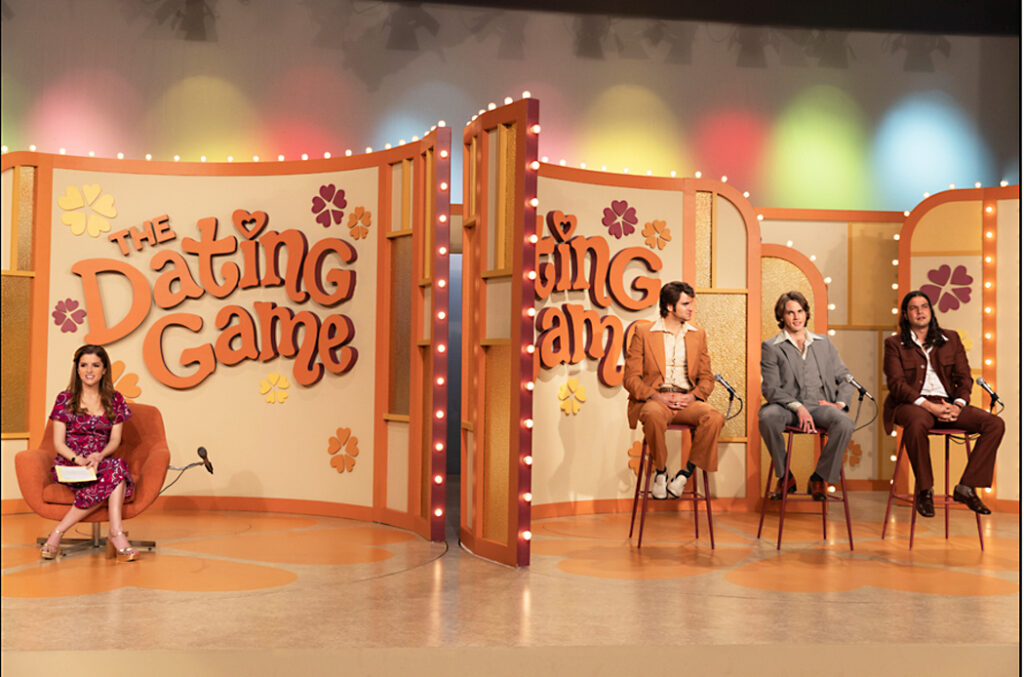

Three competing bachelors are visible to the studio audience but hidden from the female contestant on stage. The contestant poses one flirtatious question at a time to each bachelor and eventually chooses one guy. The game show couple wins a chaperoned, expense-paid getaway to some nearby destination for the chance to get acquainted. Supposedly, one Dating Game couple got married. The rest of these random couples, for all we know, might never have communicated again. As for Bradshaw and Alcala, their getaway never happened due to Bradshaw’s radar. After a brief acquaintance with her bachelor #3, she assured her agent she would never go anywhere with him because he had weird, scary vibes. Bradshaw dodged a tragedy. Though we have to wonder how the agent explained to Alcala that the trip he won was cancelled.

In Woman of the Hour, Bradshaw is played by Anna Kendrick (Up in the Air, Pitch Perfect), who is also making her directorial debut (and donating her paycheck to anti-violence charities). Playing Ms. Bradshaw, Kendrick chooses smooth-talking Bachelor #3, Rodney Alcala. She is introduced to him on stage at the end of the show. But later, he follows her outside the studio and suggests they go for drinks, a deviation from the chaperoned agenda. Bradshaw seems hesitant, but Alcala’s dominating manner wins, and she agrees. Hold that thought.

Woman of the Hour depicts Rodney Alcala as an amateur photographer who lures women with flattery. His pitch is that he’s entering their portraits in a photo competition and that she’s the perfect subject. Alcala is brilliantly inhabited by Daniel Zovatto (It Follows, Don’t Breathe), who is way better looking than this long-haired, slightly unkempt character. (Kendrick insisted he should look less attractive than the real Alcala.) Zovatto’s facial expressions and vocal tones reveal Alcala’s dark nature and his playbook. He charms his pursuit-du-jour until he can’t maintain the connection, and the real Rodney takes over.

In addition to reconstructing the 1978 TV episode with Alcala’s “TV debut,” screenwriter Ian McDonald chronicles a sampling of Alcala’s exploits through flashbacks, while we get to know the characters, some of whom are composites, which McDonald explains in his online interview with Creative Writing, is by necessity. He also expands the focus beyond Alcala because he found some of the women characters more compelling. And he succeeds in balancing the weight of a dark subject—real enough to be compelling without scaring viewers away.

Alcala seems almost genuine at first, but he can’t sustain the ruse for long. His facial expression hardens, as though his patience with faking sincerity has expired. His cordial manner darkens. That’s when the victim hears the alarm, and the shift in her speech and body language alerts Alcala that his prey has fallen out of his spell. But if he has already lured her into his car for a photo shoot adventure in a remote location, she needs a Plan B. You’ll be impressed when one victim devises one.

So why see this film? Woman of the Hour, with its benign title, offers the three “wells”: well-cast, well-written, and well executed, with satisfying twists. And the film offers something else: a reminder about our internal radar that we can honor or ignore. Sometimes we all squash signals we should obey. But since the predator species never grows extinct, any sense of warning is valuable, the sooner the better. And lest we forget, this was another era.

Life was different in the 1970s. Women were expected to be polite and respectful, even when assertive behavior was needed, sometimes for safety. We see this pattern in Bradshaw, the same woman who recognized Alcala’s dark nature and canceled their trip. But she doesn’t always honor her own needs. When a man in her apartment building (Pete Holmes) takes a liking to her, he assumes it’s mutual because Bradshaw doesn’t clarify that she is just a friend. When he puts the moves on her, she’s afraid to hurt his feelings, which is backward logic. But she sleeps with him.

This is not to suggest that a human tornado waits around every corner. Or that every danger or mishap is easily avoidable. Or that every threat or issue could cost us our life. But there are choices of all sizes that we make everyday. And we can never assume the morality of people we don’t know and sometimes never see—like in the booming industries of conning, hacking, and stealing. There’s no need for paranoia. But we can’t remind ourselves too often to stay alert and honor our instincts, and never compromise our better judgment. When the radar beeps, let’s listen.