The Inflation Reduction Act signed into law in 2022 included funding for a wide range of programs, from more IRS agents to new infrastructure and clean energy projects. But neatly tucked into a corner of this legislation was a complete redesign of the Medicare Part D prescription drug program. To fully understand the significance of these changes, a brief overview of the history of the Part D program is helpful.

Under the George W. Bush administration, Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which created the drug coverage gap, or “donut hole,” as it has come to be known. The dreaded donut hole is a temporary period when a Medicare Part D prescription drug plan limits what it will cover, essentially placing the entire cost of the medication onto the consumer. This coverage gap occurs after a specified amount of money has been spent on a drug by the plan and by the consumer. Upon entering the donut hole, the consumer is responsible for paying 100 percent of that drug cost until the coverage gap limit has been reached. Once the coverage gap ends, the consumer enters the catastrophic stage. At this point, the Part D plan pays for most of the costs for the remainder of the year, with the consumer paying only a small copay.

Although the coverage gap has evolved since its inception, it is still one of the most unpopular features of the Medicare program and is the bane of existence for seniors taking expensive medications. While most Medicare consumers do not fall into the coverage gap every year, the millions of seniors who do are sometimes faced with the painful choice of whether to buy food and pay utilities or take their monthly medications. As a result, pressure has been building on Congress to redesign the Part D program, eliminate the coverage gap, and make prescription drugs more affordable for America’s seniors.

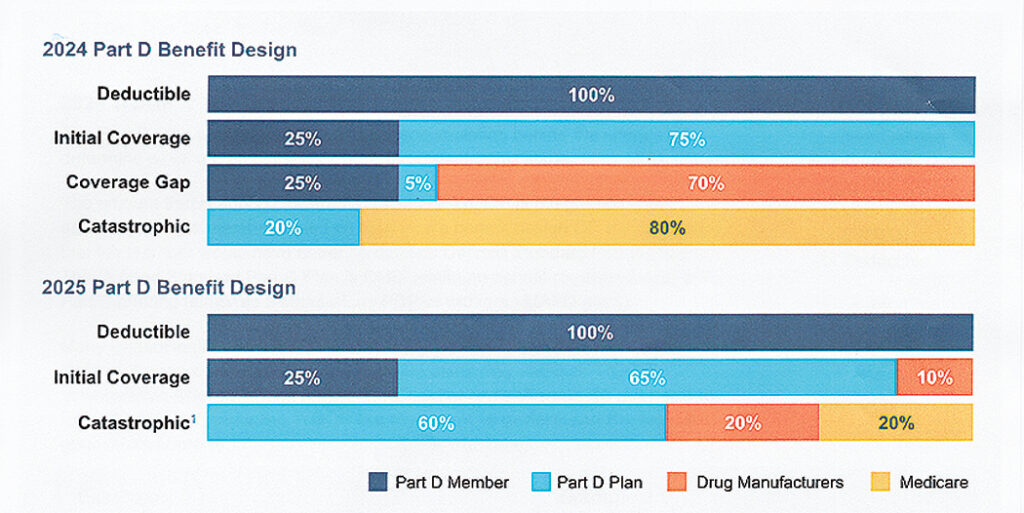

With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, a three-year timeline to enhance the Part D coverages and eliminate the donut hole was launched. In 2023, the adult vaccine program was amplified and expanded with zero copays, and the price of insulin was capped at $35. In 2024, the Low Income Subsidy program, which subsidizes the cost of prescriptions for lower income seniors, was expanded to allow for more participants, and the copay for the catastrophic stage of the coverage gap was set to zero. For the first time ever, Medicare was allowed to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies, resulting in significantly lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries. Even with these enhancements, in 2024 it is still possible for a senior to spend as much as $8,000 annually on their medication costs.

In 2025, however, we will see the most significant changes to the Part D program, with the implementation of a $2,000 out-of-pocket maximum on annual drug costs for seniors. With this new $2,000 cap on drug costs, there will be three Part D payment phases:

- Drug Deductibles Stage: While stand-alone Part D plans typically have deductibles on their tier 3 drugs (more expensive brand-name prescription drugs that don’t have a generic equivalent), most Medicare Advantage drug plans do not. That will change in 2025, with most Advantage plans now adding deductibles onto tier 3, 4, and 5 specialty drugs. This will come as a shock for the millions of seniors who have enjoyed relatively low costs for their Medicare Advantage prescriptions.

- Initial Coverage Stage: After the deductible is met, members will pay their copay, and the remaining cost of the drug will be split between the Part D plan and the drug manufacturer. Once the member has reached $2,000 in out-of-pocket costs, they will enter the catastrophic phase.

- Catastrophic Stage: The member will pay zero copay for the remainder of the year.

Beginning in 2025, Medicare will introduce the Medicare Prescription Payment Plan, which offers members the option to pay as little as zero upfront, and instead pay through a monthly payment program. This program applies to stand-alone Part D and Medicare Advantage drug plans as well. Each Part D plan will contact members individually and determine who would benefit from this new program.

After all the dust is settled, those Medicare beneficiaries who are taking expensive medications will be happy with these modifications because they will no longer incur large monthly copays as a result of being in the donut hole. However, those who are accustomed to paying nothing for their generic blood pressure or cholesterol prescriptions could find themselves paying a $500–$600 deductible.

This will be the most chaotic and disruptive Medicare open enrollment period in over a decade. Educate yourself, consult with an experienced Medicare agent, and shop wisely.

The Fairfield Public Library is hosting a free educational event on October 5 at 2 p.m. in which all these changes will be discussed.

Nikki Weaver is a licensed health and life insurance agent, specializing in Medicare.