I’ve been thinking about gun violence quite a bit lately, and I know I’m not alone. After all, the presidential nominee of one of our two major parties (or at least what is left of that party) was recently targeted by a gunman who ended up killing Corey Comperatore, a 50-year-old volunteer firefighter, who shielded his family from the attack. It is also the case, of course, that gun violence seems ever-present in American culture—so much so that folks were making jokes about the paucity of medals won by Americans competing in shooting events at the Olympics.

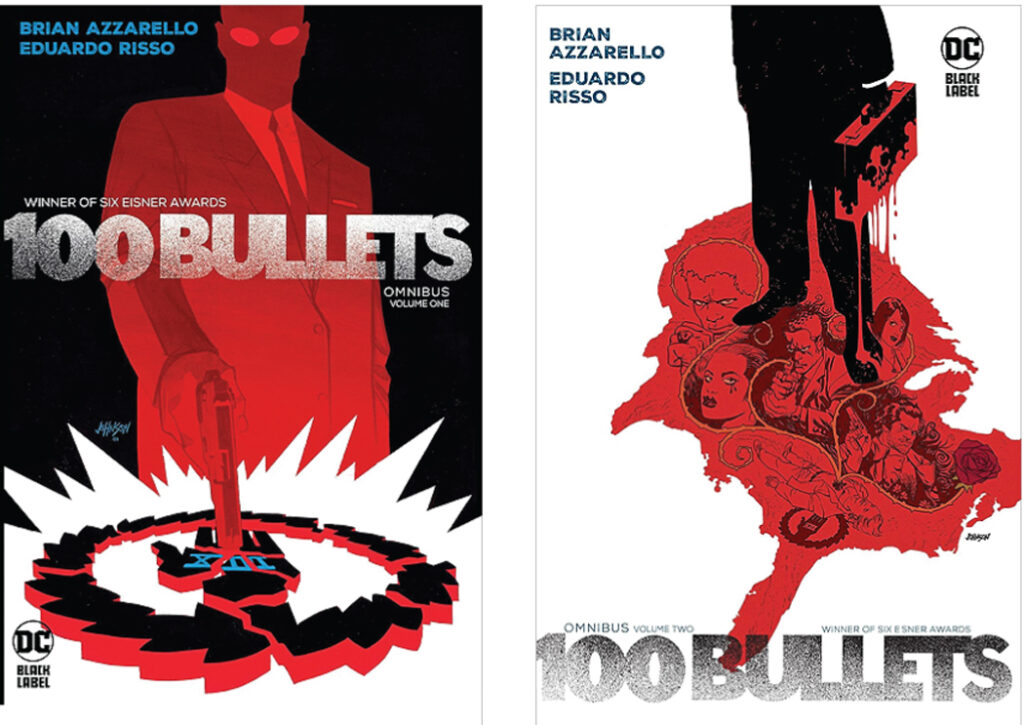

But gun violence has also been on my mind because I have been reading writer Brian Azzarello and artist Eduardo Risso’s 100 Bullets, winner of both the Eisner Award and the Harvey Award. The comic book was originally published by Vertigo as 100 individual issues from 1999 to 2009. As the title suggests, the series is much concerned with guns. Indeed, the opening conceit of the series involves the mysterious Agent Graves, who offers various individuals a handgun, the titular (and apparently untraceable) 100 bullets, and unimpeachable evidence of who is responsible for each person’s particular set of seemingly intractable problems.

The offer is revenge without consequences—or at least without consequences from law enforcement, and Graves’s targets are left to decide what they will do with the opportunity.

It’s an intriguing setup, and Azzarello and Risso bring their cast of troubled and often desperate characters to vibrant life—and frequently gruesome death. These individual morality plays are intriguing, and it is interesting to see them play out in a variety of ways. Indeed, I’d have been satisfied if the entire series had been made up of these vignettes, a kind of meditation on the nature and desirability of revenge.

Azzarello and Risso are up to something different, however. It turns out—perhaps unsurprisingly—that the seemingly unrelated incidents put into motion by Agent Graves are, in fact, related. Graves has revenge on his mind, too, as he attempts to bring down The Trust, a shadowy and unstable coalition of extraordinarily powerful families for whom Graves used to work.

As 100 Bullets continues, it becomes somewhat harder to follow and increasingly nihilistic. Loyalties and motivations are often unclear—in part because they tend to be flexible and in a state of flux, but sometimes because the narrative gets a bit opaque. A few more narrative signposts and reminders would be helpful.

Violence is always at the heart of the story, whether the focus is on a single individual with a grievance or on a worldwide conspiracy that has reached a turning point. And much of that violence is delivered by guns. (I should note here that the series also includes a significant amount of nudity and explicit sex; racist, homophobic, and otherwise offensive language; drug use; and a general air of dismissiveness for most of the female characters—though the latter is consistent with the behavior of the awful men who generally propel the story.)

Given all the real-world violence we are witness to, it is tempting to wax philosophical about whether guns should be at the heart of our leisure-time reading (or viewing or video gaming or what have you). But 100 Bullets, it seems to me, does not glorify violence. Rather, it reveals it in all its viciousness—and ultimately in all its pointlessness. Arguably, that’s a fairly profound—if not particularly hopeful—message for a series that takes its name from deadly projectiles.