As faithful readers know, I am currently engaged in a project to reread the complete 87th Precinct series by Ed McBain. The series numbers over 50 books, and in August 2022 I shared my thoughts on the first three. The books came fast and furious starting in 1956. For this column, I’m picking up the series in 1964 and covering books 18 through 23.

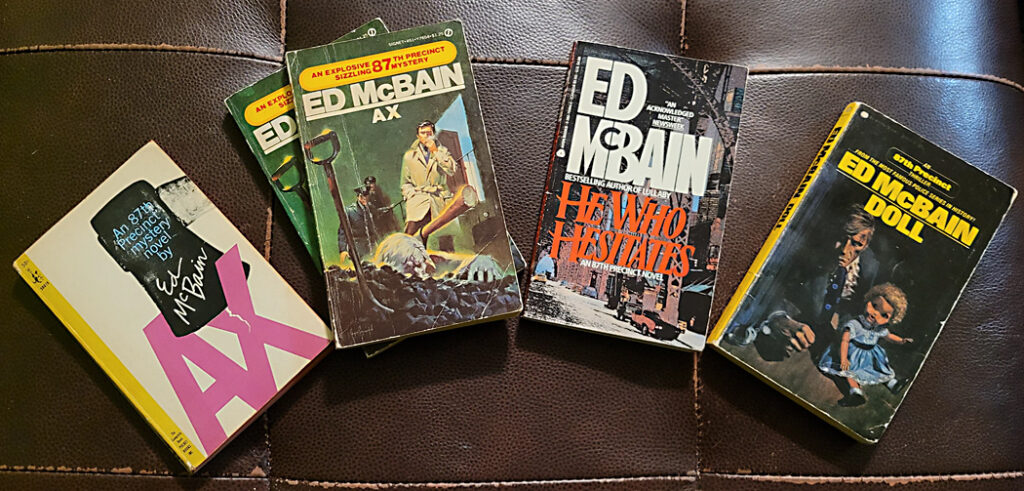

My Beloved just barely tolerates my status as a bibliophibian (one who is swimming in books). She particularly doesn’t like it when I own multiple copies of the same book. But when it comes to Ax (1964), it’s a good thing I have more than one copy. The groovy little Pocket Books edition from 1965 missed a couple of graphic elements that needed to be cut into the text. Happily, the 1977 Signet edition includes those elements, which are important to the plot. (Admittedly, that does not explain why I need two copies of the Signet edition.)

Ax is a good read that is outdated in its portrayal of mental illness but solid as a procedural. I am always amazed at the apparent prevalence of dice games as a criminal activity in entertainment of this period, but both dice and the titular ax are central to the story.

He Who Hesitates (1964) is a fascinating entry in the series because the various detectives of the 87th Precinct appear only briefly and sporadically. The story is told from the perspective of a young man who has something to tell the police, but can’t quite make up his mind whether he should do it or not. Arguably, the book drags toward the end; I was eventually a little fed up with the protagonist’s Hamlet-esque dithering.

Doll (1965) is exceptional—arguably the best book in the series to date (the Library of America folks seem to think so, too, including it in their Crime Novels of the 1960s collection). The relationships between the members of the squad are at the heart of the story, and McBain does a wonderful job bringing to life the family-like web of connections—complete with conflicts, humor, loyalty, and more.

That said, the book’s portrayal of three women—the murder victim, a cruelly rapacious villain, and Teddy Carella, Steve Carella’s beautiful, virtuous, deaf, and non-verbal wife—leaves something to be desired (a fourth woman, Bert Kling’s fiancée, Claire, who was murdered [fridged?] several books back, also haunts the tale). They each stand in contrast to the noble and brave fellas of the 87th Precinct, which . . . well . . . it’s not the greatest look. It’s notable that here in the 20th book of the series (published nine years after the publication of the first), we have only met one female detective—and then only in a single book. The good news is that the squad eventually becomes less of a boys’ club.

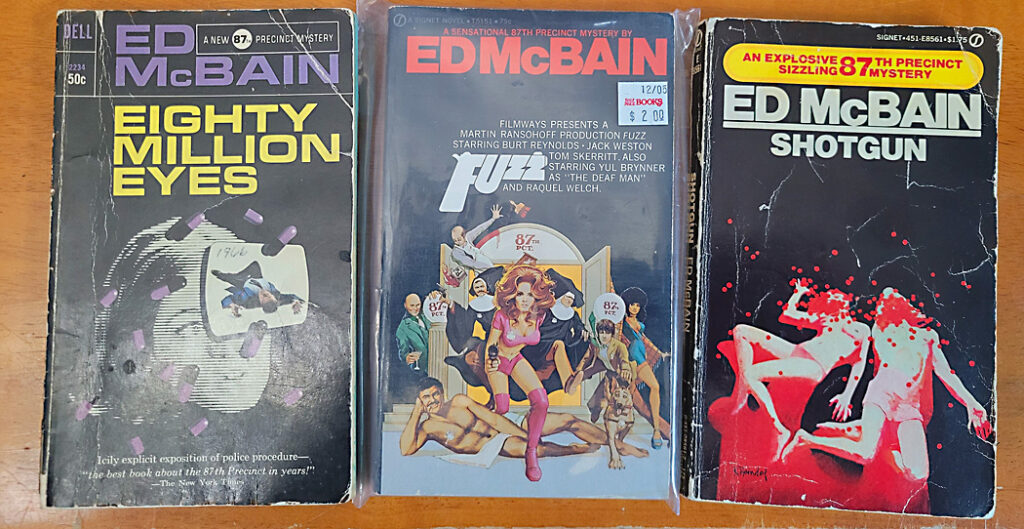

Eight Million Eyes (1966) is centered around a television program that broadcasts from the city in which the novels take place. The central plot is convoluted enough to keep readers guessing, while the secondary plot builds on the complicated relationship between Detective Bert Kling and one Cindy Forest. Cindy and Bert each lost a loved one to a sniper in Ten Plus One (1963), but their relationship was frosty from the start. That frostiness begins to thaw in this novel. Also notable in this book is Kling’s insistence that a man he is interviewing stop using the n-word.

I’d like to point out, since it is unprecedented to this point in the series, that no 87th Precinct novels were published in 1967.

Fuzz (1968) sees the return of the Deaf Man, who first appears in The Heckler (1960) and serves as the Joker to the squad’s Batman (Batmen?). It is perhaps most notable for the return of Detective Eileen Burke, last seen in The Mugger (1956)—the second book in the series. The book was turned into a movie in 1972 starring Burt Reynolds as Carella, Yul Brynner as the Deaf Man, Tom Skerritt as Kling, and Raquel Welch as Eileen (whose last name is McHenry in the movie for some reason). The screenplay is credited to Evan Hunter, who was, of course, Ed McBain. The movie (which moves the action to Boston) is more broadly comic than the book and Welch is egregiously ogled from the jump. It’s a watchable enough movie with some funny moments, and its starry cast commits to the various bits. (The cover of the movie edition of the novel probably tells you everything you need to know about the film.)

Shotgun (1969) opens with Bert Kling throwing up at the site of two people killed by shotgun blasts to the face—and that’s just one of the challenges he faces. A young woman who is merely adjacent to the investigation sets her sights on Kling and is explicit in her intentions. Kling, for his part, is not wholly happy in his relationship with Cindy Forest and is sorely tempted. A bit of romantic mayhem ensues. Anne, the young woman who just wants to go to bed with Kling, is presented as a guileless figure taking joyful advantage of the sexual revolution of the period.

Shotgun also includes a scene that harkens back to He Who Hesitates, the early entry in the series that barely features the detectives at all. The protagonist of that novel gets his comeuppance here in a satisfying scene that seems in keeping with McBain’s efforts to realistically portray police work.