For many newcomers, Iowa is an acquired taste, with its harsh winters and hot summers, muddy lakes in lieu of oceans, and flat wide spaces instead of glorious mountain vistas.

But live in Iowa long enough and the poetry of the landscape slowly seeps into your soul. You begin to perceive the other Iowa, with its subtle, almost imperceptible beauty in the changing scents and sounds of each season and the constantly unfolding wonders around you.

So it was for northwest Iowa native Maureen Reeves Horsley, raised in a tiny town in Palo Alto County. “You felt safe,” notes Horsley. “It was a good life.”

But that was long before Palo Alto County became known for something much less desirable. With cancer rates 50 percent higher than the national average, Palo Alto County has recently attracted national attention as the county with the highest incidence of cancer in Iowa and the second-highest incidence of cancer among all the counties in the U.S.

Horsley, a certified nurse practitioner, is among the growing number of Iowa residents who ask whether the cancer rates are tied to toxic chemicals linked to modern agricultural practices.

“We drank the water on our farm,” Horsley said in an interview with The New Lede on May 4, 2024. “My sister had breast cancer. She was only 27 when she died. My other sister had uterine cancer. As a nurse practitioner, I’m aware of five people now with pancreatic cancer. I know 20 people who have other cancers or died of cancer here. Look at the obituaries in our newspaper. Everybody is aware this is going on.”

The rate of new cases of cancer (cancer incidence) in Palo Alto County is 658.1, about 50 percent above the national annual average of 442 new cancer cases for every 100,000 people, according to the National Cancer Institute.

But it’s not just Palo Alto County that has come under scrutiny. The state of Iowa now has the second-highest cancer incidence among all U.S. states, with 486.6 new cases of cancer per 100,000 compared to the national average of 442. And that rate is growing faster than for any other state in the country.

The Difference Among Counties

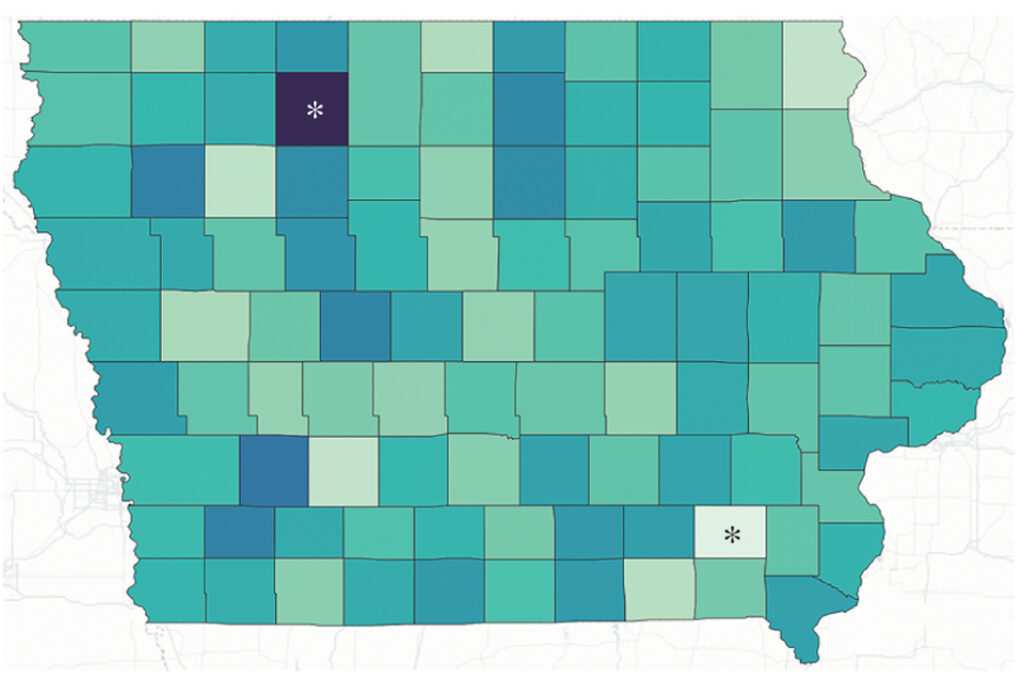

But behind the statistics is a fact that has received little attention. There is a considerable difference between the cancer rates of the different counties in Iowa.

Some counties are showing dramatically rising cancer rates, whereas others have stayed relatively stable.

Indeed, the county with the lowest cancer rates out of the 99 counties in Iowa is Jefferson County in Southeast Iowa. With an annual cancer rate of 400.1 per 100,000 people, Jefferson County not only has a lower cancer rate than the state average of 486.6, it also ranks lower than the national average of 442.3, according to the State Cancer Profiles of the National Cancer Institute.

So what gives? With such wide disparities in the cancer rates, are there trends that could give an indication of what might be causing the rising cancer rates in some Iowa counties? And, if so, what does that say about ways we might mitigate cancer risks?

Differences in Farming Operations

In the first article in this series, we reported on how some politicians and environmentalists increasingly are asking whether the growing cancer rates in Iowa could be linked to the dramatic changes in agricultural practices in the state over the past two decades.

The list of modern agricultural practices that have been linked to potentially higher risks of cancer is long. It includes:

- High levels of nitrates in drinking water from extensive use of fertilizers.

- Manure runoff from Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) creating water pollution and contributing further to raised nitrate levels.

- Poor drinking water quality caused by nitrate infiltration into groundwater.

- A dramatic increase in the use of glyphosate-containing Roundup since the 1996 introduction of genetically modified corn and soybeans that can survive being sprayed with higher quantities of Roundup. A growing number of studies link glyphosate to cancers and a range of other health issues and environment issues.

Are there differences between the two counties that could provide a clue as to why the cancer rates in Palo Alto County are 42 percent higher than in Jefferson County?

Both Palo Alto and Jefferson counties are predominantly rural counties with large swaths of farmland. Both primarily grow corn and soybeans, as is the case for most Iowa farm counties.

Palo Alto, with 342,000 acres of farmland, has 40 acres of farming operations per person, for the most part cultivated with GMO-modified corn and soybeans.

In contrast, with about 206,000 acres of farmland, Jefferson County has about 12 acres of farming operations per person, also under GMO crops. This could mean fewer issues with nitrate runoffs into private wells from fertilizer applications. In addition, Jefferson County is supplied by the Jordan aquifer, also lowering the exposure to nitrate.

Another prominent difference between the two counties is that residents of Jefferson County, through the organization Jefferson Country Friends and Neighbors (JFAN), have a successful history of curtailing the number of CAFOs in the county producing hogs and pigs.

By JFAN estimates, the hog production in Jefferson County is 20 to 25 percent lower than that in high-producing counties, such as Palo Alto County and Washington County. This means that residents in Palo Alto may be exposed to a much larger proportion of the potentially carcinogenic byproducts of farm operations. These include pesticide drift from crop spraying, nitrate runoffs from fertilizers on fields, and manure runoff from CAFOs.

In addition to the cancer risks tied to higher levels of nitrate from manure runoff, CAFOs carry a number of other health risks, including over 160 harmful gases, according to Diane Rosenberg, Executive Director of JFAN.

“Raw waste products from humans go through an expensive purification process to protect public health,” notes Rosenberg. “Raw sewage from hogs does not. You wouldn’t want to live in a county that would allow untreated sewage to be directly applied to land. Why is it acceptable in the case of hogs?”

The Protective Effects of Lifestyle

Jefferson County is also known for being the home of a large community of people practicing the Transcendental Meditation technique, with the majority of that community trending toward a healthy lifestyle.

Most people in this group have a long history of using high-quality water filters for their drinking water and favoring organically grown, unprocessed foods.

Is this another potential cause of the lower cancer rates in Jefferson County? Of course, it is impossible to say with so many different factors coming into play in the development of cancers.

However, it is well documented that up to 50 percent of cancers in the U.S. can be prevented through healthy lifestyle choices. These include eating a healthy diet, not smoking, maintaining a healthy body weight, managing stress, and exercising regularly.

Lowering Exposure to Environmental Carcinogens

Endeavors to lower nitrates in drinking water have long been part of public health efforts. And while critics argue that the EPA standards for allowable nitrate levels are too high, at the least, measures are in place to control public exposure.

This is not so when it comes to the growing exposure to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup. Glyphosate is everywhere today, whether you live in farm country or elsewhere. Today, almost 90 percent of corn, cotton, and soybean crops are modified to be tolerant to glyphosate.

The EPA estimates that 280 million pounds of glyphosate are used each year on 298 million acres of agricultural land. Glyphosate is also used in lawns, gardens, landscaping, roadsides, and schoolyards. It is a common ingredient used to battle invasive plant species in public parks and forests.

Glyphosate in the Foods We Eat

Eighty-four percent of glyphosate pounds used in agriculture are applied to soy, corn, and cotton, commodity crops that are genetically engineered to tolerate large quantities of glyphosate that would normally kill a plant. Glyphosate is also widely used in fruit and vegetable production.

In addition, glyphosate is sprayed just before harvest on wheat, barley, oats, and beans that are not genetically engineered. This practice is known as preharvest crop desiccation. Glyphosate kills the crop, drying it out so it can be harvested sooner than if the plant were allowed to die naturally.

Perhaps not surprisingly, exposure to glyphosate now comes not just from living in states with extensive farm operations, but also from the food we eat. Glyphosate

has been found in more than 95 percent of popular oat-based food samples as well as in wheat-based products, including pasta and cereal, according to the Environmental Working Group (EWG).

In other words, we are all part of what may well turn out to be the largest biological experiment in the world’s history. Studies have found detectable levels of glyphosate in urine in 80 to 99.8 percent of the urine samples collected. Does that constitute a health risk, and if so, how much is too much?

Not surprisingly, this is the subject of a heated debate. Environmental advocates argue that the EPA’s current regulatory limits for glyphosate in food are far too low. The EPA has raised the permitted levels of glyphosate residues on certain foods, following a Monsanto petition.

The link between glyphosate and a number of different cancers, particularly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is now well documented. But we are still in the early stages of understanding the effects of widespread, long-term exposure to glyphosate.

A slew of more recent studies are now showing correlations between higher urine levels of glyphosate and various health conditions, including metabolic issues, lower cognitive function scores, severe depressive symptoms, and severe hearing difficulty.

Many Questions, Few Answers

We are still in the early phases of understanding the changing trends in modern ag practices over the last 20 years. Research so far has raised many red flags. However, there are still more questions than answers. While studies have found numerous associations between changing ag practices and a wide range of health issues, there could be other underlying factors driving these correlations that we are not yet aware of.

A longstanding concern has been high levels of radon. In addition, contaminants in drinking water have been flagged as a public health risk in Iowa. Contaminants like arsenic and atrazine (another widely used pesticide in the corn belt) have been present in both public and private drinking water for decades.

The takeaway? Cancer risks in Iowa are nothing new. However, it could be that an increasing environmental toxicity load—added to existing influences—is pushing more people over a threshold where the body’s natural detoxification and immune system processes begin to break down.

Until more conclusive answers are available, your best bet is to make your own decisions about reducing the toxicity load on your body.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

Fortunately, there are numerous things you can do to mitigate the risk posed by environmental toxins.

To lower your exposure to nitrates in the drinking water, consider installing a high-quality water filter specifically designed to remove not just nitrates, but other contaminants like arsenic, which has also been found in Iowa wells. Reverse osmosis and ion exchange filters are most effective. Also, be mindful of other nitrate exposures, such as swimming in contaminated lakes and rivers.

In addition, take steps to reduce your exposure to glyphosate. If you live near farms, you can minimize exposure from spraying and drift by closing windows during spraying and removing shoes before entering your home.

If you are concerned about glyphosate levels, ask your doctor for a simple urine test to measure your glyphosate levels (several do-it-yourself tests are also now available online). Some companies now also offer glyphosate strip tests to help you measure the levels of glyphosate in your foods.

Glyphosate is constantly being secreted from our bodies. You can support your body’s natural detoxification systems by eating an organic diet rich in cruciferous vegetables and drinking plenty of filtered water. Also consider supplements that support natural detoxification like calcium D-glucarate, milk thistle, and glutathione.

As the tale of these two Iowa counties illustrates, a vast number of factors impact both cancer risk as well as survival. Fortunately, many of the factors that will lower your risk will also help you enjoy greater well-being, a reduced chance of chronic disease, and a healthier aging trajectory. What’s not to like?

See Iowa’s High Cancer Rates: Part I.