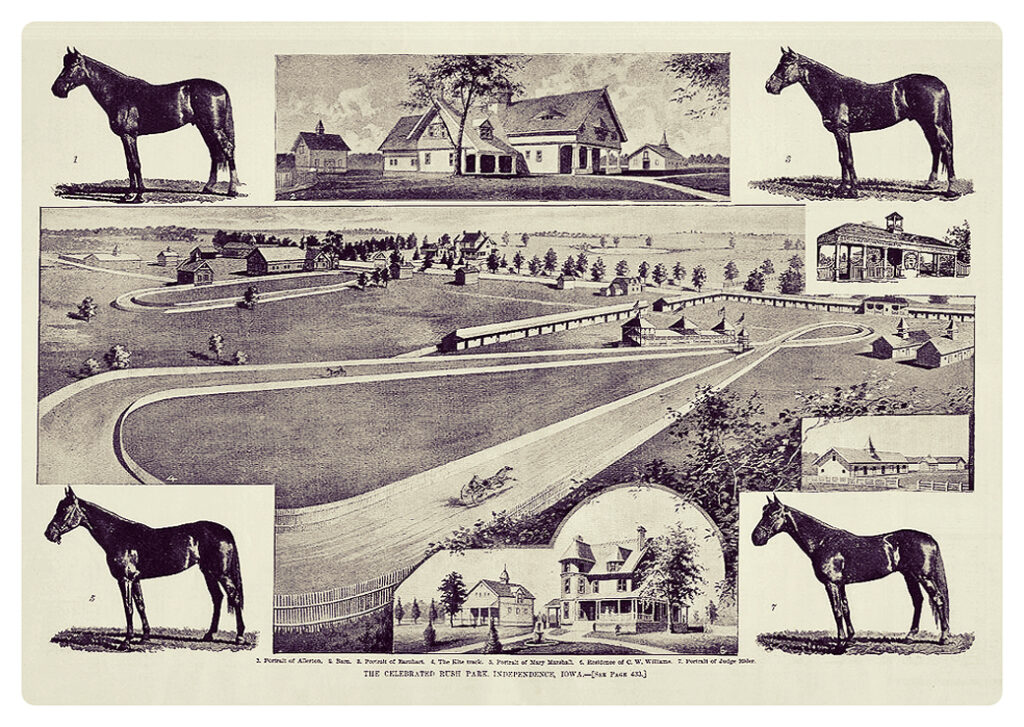

In an issue of The New York Times on February 20, 1899, there was a curious article on an unexpected visitor at a horse sale in that city. The visitor was Charles W. Williams, from Galesburg, Illinois. He was recognized by reporters as a former celebrity in the world of horse racing. It seems he had once been the owner of a world-famous trotting horse, a sire named Axtell, who had set a world record on Williams’s kite-shaped racetrack at Independence, Iowa. But that had been almost a decade before, and Williams’s luck had plummeted.

Indeed, those who spoke to Williams that day were surprised by how oddly he was attired. He “looked like 30 cents,” one person remarked. He was dressed in a “shabby ulster [coat], wearing a sorry looking derby hat, with a week’s growth of beard, and shocking shoes.” Indeed, the writer continued, he “looked rather like a stable attendant” instead of “the one-time Pooh-Bah of Independence, Iowa.”

The article goes on to provide the details of the decline of his career. At the height of the trotting boom, Williams “had ‘all kinds of money,’ . . . spent it liberally, built a kite-shaped race course . . . started a paper devoted to the horse, built a fine hotel [The Gedney], theatre, and bank in Independence, and tried to boom the town. But a pinch came, the boom collapsed, the newspaper suspended, real estate was a drug in the market, and everything, including the kite-shaped track and Independence itself, went by the board.” When the dust had settled, “Williams was at the bottom of the wreck and completely crushed by it.”

Just a few years earlier, when Williams had been at the top of his game, one of his youthful employees had been a boy who loved working with horses, but wanted even more to become an artist. His name was William Edwards Cook, and in time he would leave Iowa to study art at schools in Chicago, New York, and Paris. In Paris he became good friends with the American expatriate writer Gertrude Stein.

The first time that Cook attended a party at the famous apartment of Stein and her brother Leo, at 27 rue de Fleurus, he met another expatriate who was also attending a Stein soiree for the first time. Her name was Alice B. Toklas, and she would soon become Gertrude Stein’s partner. Toklas was terribly nervous that night, and was ever so relieved to meet another American. When she asked Cook where he came from and he replied “Independence, Iowa,” she could hardly contain her excitement. Toklas had grown up in California, but when she was young, Independence had often appeared in the national news, and she and Stein were well aware of the story of Williams’s top stallions, Axtell and Allerton.

It seems that nearly everyone knew about Charles (known as C.W.) Williams, his horses, and his kite-shaped track. As noted by a writer then, “Independence is a world-famed little city. . . . [There is] No need now, when speaking of Independence, to add Iowa; everyone knows what is meant.” Williams sold Axtell to a syndicate for $105,000, equal to multimillions now, the most ever paid for a racehorse. Later, despite his and others’ losses from an economic crash in 1892, he did not sell Allerton, but quietly rebuilt his wealth from the stallion’s lucrative breeding fees.

Williams left Iowa in 1894, transported in 18 railroad cars that carried his earthly belongings and a string of 54 horses. He had been persuaded to move to Galesburg, Illinois (the site of the Lincoln-Douglas debate), where his success in horse racing and breeding continued. He organized the Galesburg District Association, designed a brand-new racetrack, and featured a new black mare named Alix, who was owned by a couple from Muscatine. Alix held the world trotting championship for six years, from 1894 to 1900, having acquired that distinction at Williams’s Galesburg track, which was not kite-shaped, but looked like a railroad coupling pin, with “dead level” parallel prongs.

During Williams’s first year at Galesburg, among those working at the track was a stable hand and water boy, the son of Swedish immigrants, named Carl Sandburg. He was not well-paid, but, as he recalled in his memoirs, “I had a pass to come in at any time and I saw up close the most famous trotting and pacing horses in the world, how they ran, and what the men were like who handled and drove them.” He also got to be around Charles Williams, if from a polite distance. “He was a medium-sized man with an interesting face,” Sandburg remembered. “I thought his face looked like he had secrets about handling horses, yet past that there was a solemn look that bordered on the blank—I couldn’t make it out.”

In 1914, Williams was referred to in a news account as a “reformed race horse man,” who had been converted to “old-time religion” after he settled in Galesburg. At some point, he traded all his horses in exchange for more than 33,000 acres of farmland in Saskatchewan in Canada. Once there, to visit all the farms he owned, he had to drive 350 miles. At the time, he was believed to be the largest individual grain farmer in North America.

He was now free to travel more, and he soon took up the part-time role of an itinerate evangelist—as Sandburg put it, he had hit “the sawdust trail”—speaking at churches in Galesburg and surrounding towns, while also returning to Iowa where he held revival meetings at Waterloo, Jesup, Independence, Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, and Mount Pleasant. In 1925, three decades after moving from Independence to Galesburg, Williams moved to Aurora, Illinois, where he established a small stock farm for breeding registered cattle, which he called Axtell Herefords. He died there eleven years later, in February 1936.

In his autobiography, Carl Sandburg recalled the last time he saw Williams. It was on a passenger train from Chicago to Galesburg. “He sat quiet in a seat by himself,” remembered the poet, “and I could no more read his face than I could twenty years earlier. I like to think about him as I saw him once on an October morning, a little frost still on the ground, in a sulky jogging around the only dead level racetrack in the world, driving at a slow trot the stallion Allerton, being kind and easy with Allerton, whose speed was gone but whose seed were proud to call him grandsire.”

More About C. W. Williams

Additional information about Williams’s career can be found in W.J. Petersen’s “The Lexington of the North,” a special issue of The Palimpsest (State Historical Society of Iowa), October 1965. Williams and Cook are also discussed in Roy Behrens’s documentary film, COOK: The Man Who Taught Gertrude Stein to Drive (Youtu.be/oph7fCHHHNI), as well as in his book, COOK BOOK: Gertrude Stein, William Cook and Le Corbusier (Bobolink Books, 2005). Carl Sandburg’s memories of Williams are in his autobiography, Always the Young Strangers (Harcourt Brace, 1953).

Roy R. Behrens is an Iowa-based writer, designer, and artist. Find more information at Bobolinkbooks.com/ballast/sitemap.html.

4) Steel engraving portrait of Williams, showing what may be the “ulster coat” and “derby hat” (still in good condition) that The New York Times described in 1899.

<https://youtu.be/oph7fCHHHNI>,

http://www.bobolinkbooks.com/BALLAST/sitemap.html>

Main text is 1,100 words

.

Roy R. Behrens is a designer, writer, and retired university professor. His most recent book is Frank Lloyd Wright and Mason City: Architectural Heart of the Prairie (2015). For more information, see BobolinkBooks.com/ BALLAST.

<http://www.bobolinkbooks.com/BALLAST/>.