Legendary artist and openly gay activist Keith Haring (1958–1990) is the subject of a new exhibition opening this month in Iowa City. To My Friends at Horn: Keith Haring and Iowa City debuts at the Stanley Museum of Art on Saturday, May 4.

Highlighting Haring’s little-known connection to Iowa, the exhibition was deliberately scheduled to open on what would have been his 66th birthday. Centered around Haring’s 1989 mural, A Book Full of Fun, which he painted at Iowa City’s Ernest Horn Elementary School, the exhibition utilizes art, photographs, and archival materials to celebrate Haring’s community-building visits to Iowa City in the 1980s, while contextualizing those visits within his phenomenally explosive, tragically short career.

“We knew we wanted the exhibition to open in time for Iowa City Pride, and I felt it would be especially festive to open on Keith Haring’s birthday,” explains Diana Tuite, the Stanley’s visiting senior curator of modern and contemporary art and the exhibition curator. “The 35th anniversary of the mural’s creation falls later in the month (May 22) and it’s a busy time of year for visitors, including school groups.”

Born in Pennsylvania and based in New York, Haring was committed to making art accessible to everyone by using public places as canvases. Known for his bold, graphic illustrative style and using now iconic figures such as the barking dog and the radiant crawling baby, Haring’s vibrant murals and popular subway drawings catapulted him into international fame in the 1980s. Haring’s art promoted racial and sexual tolerance while addressing social and political issues such as nuclear arms, environmental destruction, sexual identity, and the AIDS epidemic. The majority of his career was devoted to public works, and he created murals and installations for charities, day-care centers, orphanages, hospitals and schools. Haring produced over 50 public art pieces between 1982 and 1989, and participated in more than one hundred group and solo exhibitions.

A firm believer in the importance of art in education, Haring worked with many schools. Ernest Horn Elementary School art educator Colleen Ernst was actually responsible for bringing Haring to Iowa for his first visit, in 1984. Affectionately known as “Dr. Art,” Ernst had introduced her fifth- and sixth-grade students to Haring’s work, and shared her students’ enthusiasm in a postcard sent to Haring. This began a correspondence involving letters and care packages between the artist and the grade-schoolers.

“This exhibition demonstrates how we all function as keepers of important community histories,” Tuite explains. “Colleen Ernst is an extraordinary and incredibly modest individual; she was the fulcrum for these events 40 years ago. The show revisits an educational culture that is, by and large, gone. In our school systems, energy is expended to exercise control, narrow inquiry, discourage expression, and disallow dialogue.”

She adds, “This exhibition reminds us of what can be possible when creative and collaborative thinkers—and I’m including Keith Haring here—are given the freedom and support they need to realize their vision. As he said in one of his faxes to Colleen, ‘Education is the key.’ Keith Haring lived as an openly gay man and knew how meaningful his presence could be in many communities, particularly as the AIDS epidemic surged.”

Traveling to Iowa City in March 1984, Haring did a three-day residency, organized in partnership with the University of Iowa. Haring conducted workshops with students, completed a painting at the Old Capitol Center while accompanied by the Johnson County Landmark Band, and lectured at the University of Iowa Museum of Art, where he had a small exhibition.

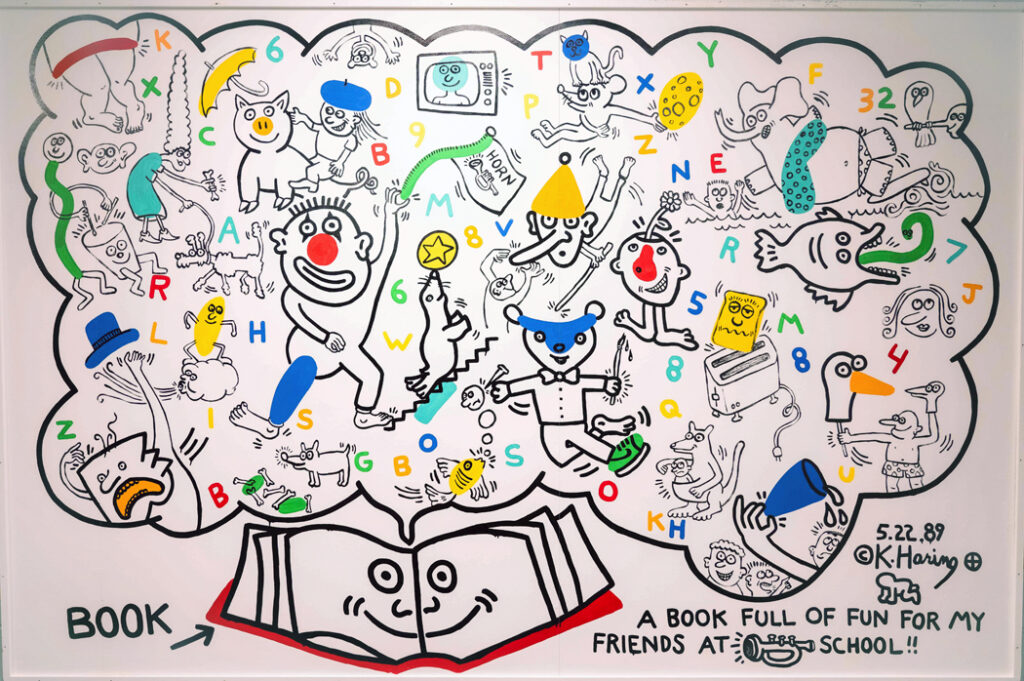

After returning home, Haring continued corresponding with students, frequently using the salutation “To All My Friends at Horn,” which inspired the current exhibition title. He returned to Iowa City for one day in 1989. On May 22, dubbed “Keith Haring Day,” he painted a tribute to literary imagination: the mural A Book Full of Fun. Now on loan to the Stanley, this mural depicts an open book with a thought bubble above it swirling with whimsical characters, letters, and numbers.

Haring, who was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, died at age 31 from AIDS-related complications, less than a year after painting this mural. Before his death, he established the Keith Haring Foundation, which provides funding and imagery to AIDS organizations and children’s programs. The Foundation, still very active today, partnered with the Stanley Museum of Art and Horn Elementary School to preserve A Book Full of Fun, which was carefully removed from the Horn and transported to the Stanley. Documentation of its innovative conservation and restoration progress is featured in the exhibition.

“The original plan was to just exhibit the mural—which is on loan from the school—at the museum,” Tuite says. But as she looked deeper into Haring’s two visits, she saw “the potential for an exhibition here because these two encounters bracket the mature years of Haring’s tragically short career. There are many places he visited once, but few that he sustained this kind of relationship with and returned to again, especially in the final year of his life.”

Once the decision was made for a full exhibition, Tuite says, “things happened very quickly,” adding, “We recognized early on that this show should crowdsource memories, knowledge, and artifacts from members of the community. I conducted interviews with folks that will eventually be featured in a video in the exhibition and borrowed items from individuals kind enough to share them with us.”

Tuite “set out to design a focused but rich show that would encapsulate the breadth of Haring’s career.” Three pieces borrowed from the Keith Haring Foundation “help visitors appreciate the fullness of his body of work and will stimulate dialogue with other art in the collection.” One piece is a 1979 video Haring made as a student at the School of Visual Arts. “He filmed himself making a giant painting on the floor,” Tuite explains. “This will help audiences appreciate how he was thinking about his artwork as environmental, performative, and public-facing from the outset. It’s also a fantastic way to draw a connection to a work like Jackson Pollock’s Mural, perhaps the best-known work of art in the Stanley collection.”

Tuite hopes visiting the exhibition will help “people reflect on the ways that artists and teachers have impacted their lives as they consider the values that Keith Haring’s life as an artist-activist embodied.”

For more information, visit Stanley Museum of Art.