In the Iowa town where I grew up, the city’s public schools were called Washington, Emerson, Lincoln, and Hawthorne. Indeed, throughout the country, it was common for public schools to be named in honor of these individuals. I attended Emerson School for five years, from kindergarten through fourth grade, then spent two years at Washington for the fifth and sixth grades.

Back then I knew little or nothing about the New England poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), who was among the founders of Transcendentalism. I was certainly unaware that he had toured the country in the mid-19th century, giving talks in 20 states, including Iowa. Indeed, few speakers were as popular, as shown by the fact that Emerson gave 1,500 talks in more than 300 American towns.

According to a 1927 article by Iowa historian Hubert H. Hoeltje, titled “Ralph Waldo Emerson in Iowa,” Emerson first saw Iowa in the summer of 1850, but only from a distance. He viewed it from the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, near Galena. It was not until five years later that he set foot on Iowa soil, by which time it had been a state for nearly a decade. In 1855, he was invited to lecture in Davenport, but at that time, there was no bridge. Fortunately, he arrived in very late December, and the river was covered with ice. For the third time (the first two at St. Louis) he walked across “Old Man River” on foot.

On New Year’s Eve that year, Emerson spoke at the Congregational Church in Davenport. The admission price was 50 cents. The event was not well advertised, and the speaker was nonchalantly said to be an “essayist and poet.” We do not know what Emerson said, nor do we know the title of the talk, if there was one. A reporter in the audience said that the presentation confirmed that “[Emerson] writes and reasons well.” At the same time, “he is no orator.” He sauntered from topic to topic, the writer complained, such that his talk was not unlike the Laocoön Group, the famous Greek sculpture in which a man and his two sons are hopelessly entangled in a struggle with sea serpents.

At the time of that first Iowa talk, Emerson may still have been feeling the after-effects of a courageous forthright statement he made some four years earlier. In May of 1851, while speaking in Concord, Massachusetts, he had openly denounced the “fugitive slave law,” which required citizens in the North not to impede but enable the capture of runaway slaves and their return to Southern enslavement.

In that speech, Emerson condemned the law as “one which every one of you will break on the earliest occasion” and “which no man can obey.” It is a “filthy enactment,” he wrote in his diary, “made in the nineteenth century by people who could read and write. I will not obey it.” It is to Emerson’s credit and to others of his time that the law was partly undermined. As those opposed to slavery grew in numbers, personal liberty laws were passed, and there was increased subversion through the Underground Railroad. Iowa was among those states in which there was a network of safe houses for concealing fugitive slaves.

Of those at Emerson’s Davenport talk in 1855, most were probably well aware of his opposition to slavery. Earlier, when Iowa had been granted statehood, its citizens had determined by vote that it should be a “free state,” in which slavery would be banned. In contrast, the bordering state of Missouri was pro-slavery. In 1859, shortly after Emerson’s talk, the abolitionist John Brown and his colleagues (some of whom had secretly trained in Iowa) would mount their fateful failed attack on the Harpers Ferry Armory in Virginia. Soon enough, the bloody Civil War broke out.

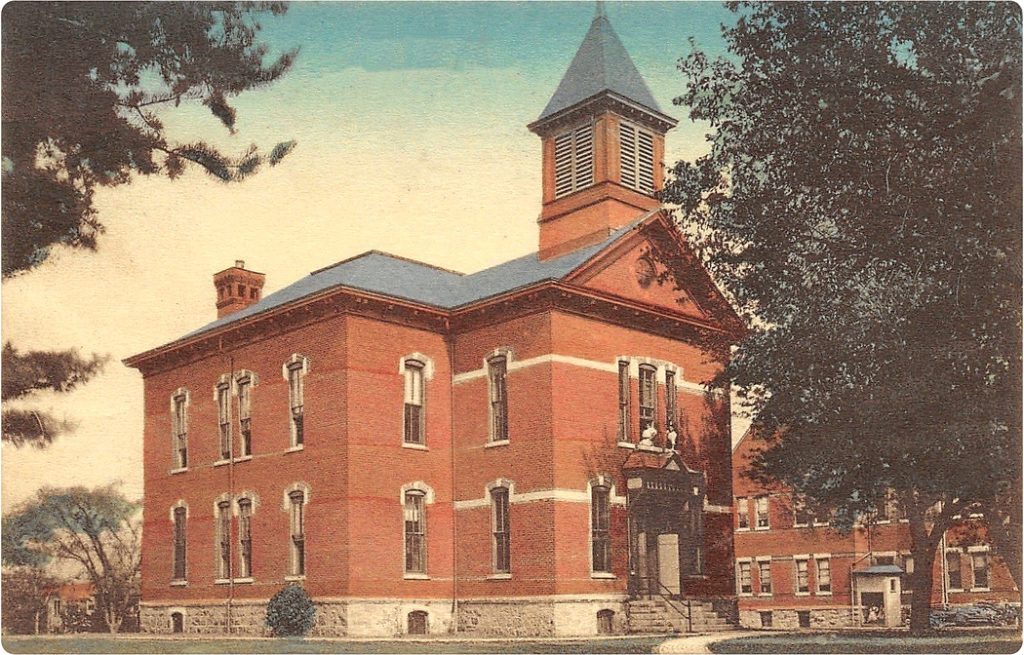

Given those circumstances, Emerson did not return to Iowa until the war had ended. He was once again invited to Davenport on January 19, 1866. His talk this time was well received and respectfully well attended, but the number was less than expected. Because of bitter cold and winds, it was an “inauspicious night.” From there, he traveled to Lyons (now part of Clinton) to speak, then took a train to nearby DeWitt, where he was slated to appear at the Methodist Church at 7:30 p.m. on January 23.

He reached DeWitt in ample time, but he was soon in a panic. He had not known the starting time of his talk, and he had reason to be concerned because his next appearance was scheduled for the following day in Dubuque. In order to get there that evening, he would have to rush through his talk at DeWitt, so as not to miss the evening train. It was an awkward arrangement, as soon became apparent to the speaker and those in attendance. Later, a DeWitt news report was blunt: Emerson was so openly worried about “making the train” that “he consulted his watch so frequently that it became a bore” to the audience. Worse yet, “he thumbed over at least one half his manuscript unread,” such that one might be led to suspect that his talk was a “genteel way of swindling people.”

In the end, he did catch the train to Dubuque, where his talk was well-received. “Every sentence was a gem,” a newspaper claimed. “When he had finished, one’s brains felt like a tooth just filled—the gold crowded in and hammered down.”

Emerson returned to Iowa in February of 1867 for appearances at the Methodist Church in Washington and the Baptist Church in Independence (reached by stage coach), where he spoke as a substitute for Horace Greeley (as in “Go West, young man!”), and from there to Cedar Falls. His remaining Iowa talks that trip were at Keokuk, Des Moines, and Burlington.

He returned at the close of the same year to speak at Keokuk again. To get there from the Illinois side, he again crossed the Mississippi, but since it was not reliably frozen, he was transported in a skiff that was rowed across on the surface of the ice. He traveled west to speak again in Des Moines, and, on the return trip, he spoke in Davenport for the second time as well. Emerson’s last talks in Iowa took place at the Athenaeum Theatre in Dubuque, on December 8, 1871, and on the following Sunday at the Unitarian Universalist Church.

Emerson was 68 that year, and his public talks, as Hoeltje notes, were increasingly “a visible strain, for he seemed to hesitate more than formerly, as though he were overburdened with solicitude in his choice of words.” He was experiencing memory loss and aphasia, and today, we might suspect that these were early indications of Alzheimer’s or other dementia.

Retiring to his Concord home, the decline of his memory hastened. In his last years, there were times when he could not remember his name, and when asked how he was feeling, he would say, “I have lost my mental faculties, but I am perfectly well.” When he died of pneumonia in 1882, he was buried on “author’s hill” in Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (not the earlier one in New York), near the graves of various friends, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Louisa May Alcott.

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, graphic designer, and artist who taught in art schools and universities for more than 45 years. Find more information at BobolinkBooks.com/ballast.