Frank Lloyd Wright and Grant Wood differed in significant ways. And yet, as artists and designers, they had enough in common that—metaphorically speaking—they might be mistaken for cousins.

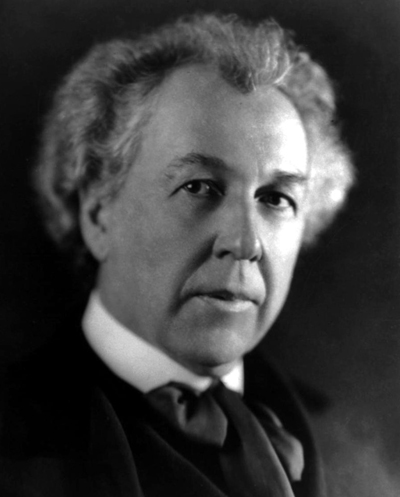

Wright was born in Wisconsin in 1867, two years after the terrible death of Abraham Lincoln. The name that he was given at birth was Frank Lincoln Wright, and he later changed it to Frank Lloyd Wright, to honor his mother’s ancestral name.

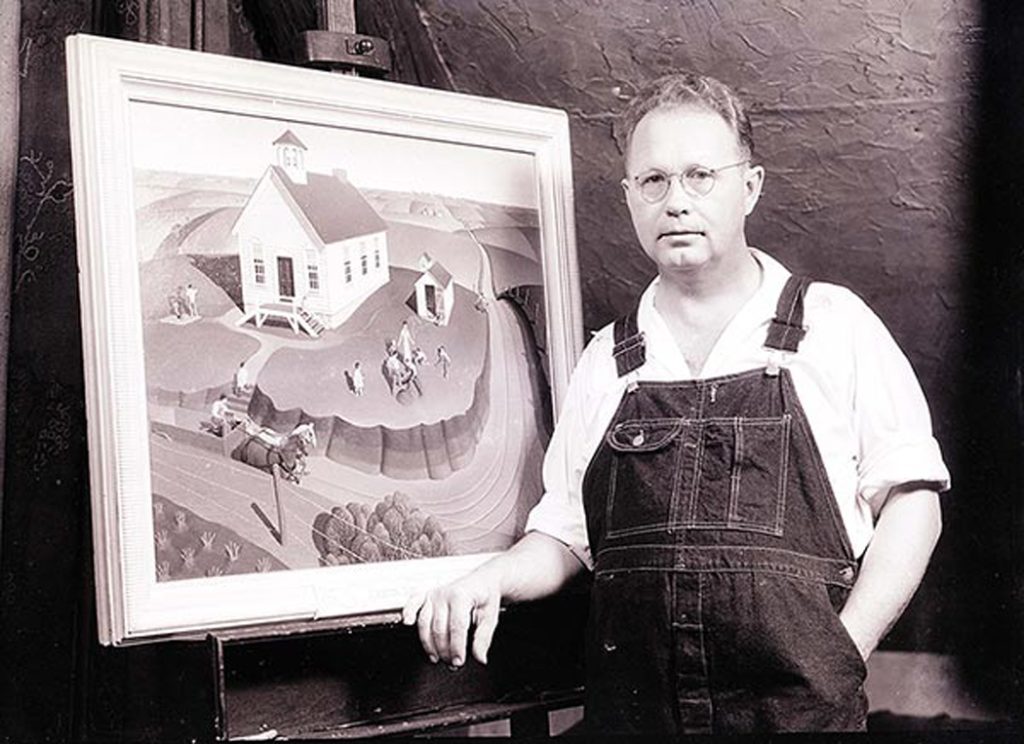

Grant Wood was also a Midwesterner. Born near Anamosa, Iowa, in 1891, he too may have been named in honor of a hero, Union Army commander and American president U.S. Grant.

Wood was substantially younger than Wright. At the time of Grant Wood’s birth, Wright was already well on his way to becoming a prominent young architect in Chicago, where he was the primary draftsman for Louis H. Sullivan, whom he considered his mentor.

Grant Wood’s life ended early when he died of cancer one day short of age 51 in 1942. Frank Lloyd Wright lived on for many years. He was 91 when he died in 1959. All told, the two co-existed in time for a half century, and for a dozen or so of those mutual years, they were both well-known Americans. Surely, they were aware of each other’s celebrity, and yet, it is not clear if they actually met.

Wood was reputed to be soft-spoken, affable, and modest. Wright was notoriously irascible, prone to making offensive remarks. There is no doubt that Grant Wood was interested in architecture—after all, his best-known painting (American Gothic) pays homage to an architectural style. But if he had any opinions about Wright’s architecture, they were apparently never recorded.

There was at least one occasion when Wood and Wright were in the same place at the same time—or at least in the same city. In July 1939, both were invited to speak in Iowa City at a weeklong Fine Arts Festival at the University of Iowa. At the time, Wood was on the faculty there, where he taught painting. During the festival, he was scheduled to appear at a luncheon on Monday (the first event of the week). In addition, a dozen of his paintings, including American Gothic (never before shown in Iowa City), along with the work of other artists, were exhibited in the Iowa Union.

Frank Lloyd Wright was invited to give the final address at the close of the festival. On Friday evening, he spoke to an outdoor crowd of about 1,500 people on the west lawn of the Old Capitol building (which he tactlessly described as “a little old court house”).

The following day, on Saturday morning, when he spoke again at a round table talk in the same building, he was introduced by the festival’s organizer, who included an awkward disclaimer: “Our visitor today said to me that he came to us as a physician comes to a patient. He did not come to praise, unless he found valid reason. . . . And, as nearly as I can judge, he has found little. . . . My own wish yesterday [in time spent with] this physician was that he would occasionally administer at least a mild anesthetic.”

One wonders if Grant Wood attended Wright’s presentations. If so, he surely must have been dismayed by Wright’s injurious comments. According to Zella White Stewart (an actual physician), who witnessed both events, Wright “took a crack at [just] about everything.” He dismissed the paintings on display as “art without a soul…[and thus evidence of] a lack of soul within the people.” In a news report that followed, he was quoted as describing the artworks as “painting—not art.” Wright was, Stewart continued, “the first visitor to tell us that Grant Wood’s paintings were not a high form of art.”

It is of interest that this Iowa City event took place about five weeks in advance of the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, an event that prompted World War II. As Fascism gained the upper hand in Europe, Grant Wood was also under threat in Iowa, for other reasons. Several members of the university community, who had been sowing suspicions about Grant Wood’s sexual leanings, were also ardent advocates of Modern-era painting trends, and they were intent on discrediting Wood. He had studied art in Germany in the 1920s, and it was implied that his folksy Regionalist painting approach was somehow in lockstep with propagandistic figurative art, as championed by the Nazis.

Over the years, quite a lot has been written about Wood’s paintings in relation to his private life. They have been heavily harvested for hidden meanings. At the moment, it is common to peruse his work in search of repressed erotic content, in which case pointy things are said to be sexual symbols, whereas other aspects are evidence of something else. Such speculation is engaging to a degree, but it can also be tenuous, as when camels and weasels appear in the clouds in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Like those who see veiled implications in Grant Wood’s compositions, Frank Lloyd Wright was himself adept at unearthing latent structures in otherwise seemingly innocent plans. Among the best examples of this is a story that was told by one of Wright’s associates, the architect Edgar Tafel, in About Wright. He recalled that a committee from a certain church once met with Wright to discuss their requirements for a new worship facility. Wright agreed to produce a building plan, which he would present in a couple of weeks.

But Wright’s studio staff was overwhelmed by other commissions, and they never found time to work on the church. As the deadline approached, Wright was advised by his staff to postpone the meeting with the church group, since the plans had not even been started.

Instead, at the very last minute, Wright pulled out of storage a set of abandoned building plans that he had drawn up for a small shopping center, a project that had fallen through. According to Tafel, Wright changed the labels for the shopping center spaces to comply with the needs of the church: “the [shopping center] bank became the [church] sanctuary, the supermarket became the Fellowship Hall, the [retail] stores [were repurposed as] classrooms, and on and on.”

By the time the church committee arrived, the set of plans had been renamed, “and Mr. Wright showed them the drawings, with accustomed gusto and aplomb.” At the end of Wright’s presentation, “the pastor said: ‘Lord, we thank thee for leading us to a great architect, who has designed, in your honor, an edifice we will use and enjoy. Amen.’”

Roy R. Behrens is an artist, designer, and teacher. In 2016, he published a book on Frank Lloyd Wright and Mason City: Architectural Heart of the Prairie. For more information, see BobolinkBookscom/ballast.