In the spring of 1891, a 72-year-old woman was mailing a letter at the post office in San Jose, California, when a man—who was exceptionally large, unsteady, and walking at a frantic pace—suddenly collided with her.

His head struck hers so forcefully that she fell against a nearby wall, leaving a gash on her forehead. She regained her composure and appeared to recover in a few moments. But several days later, she began to experience swelling, bleeding, weakness, and other effects.

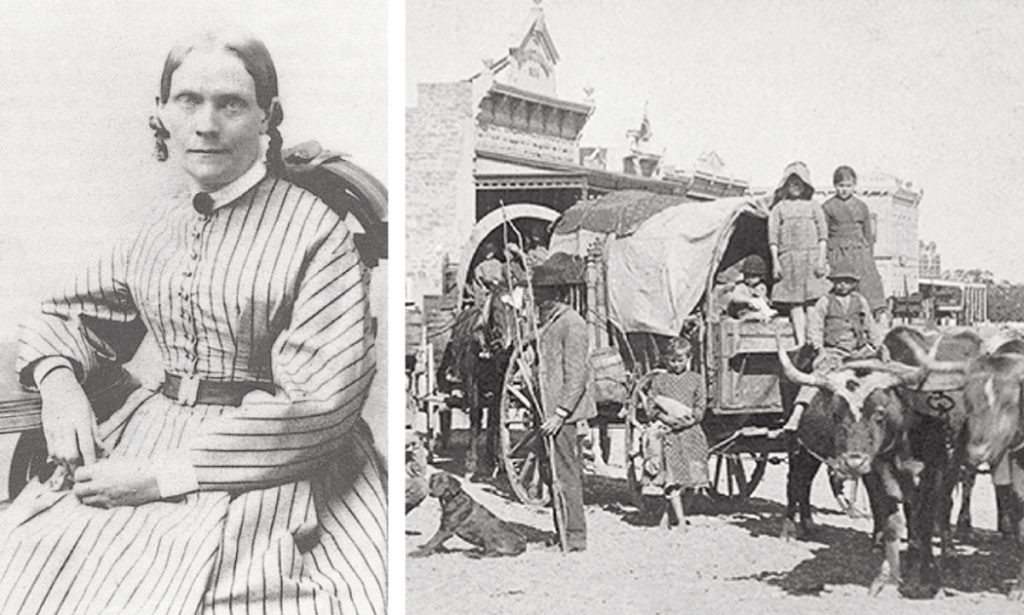

In the months that followed, her health continued to decline, and she died at home of “nervous shock” on the evening of Tuesday, November 24, 1891. Her married name was Sarah Royce, while her parents’ family name was Bayliss. Originally from England, she had been born in 1819 in Stratford-upon-Avon, William Shakespeare’s birthplace. When she was only six weeks old, her family immigrated to America and settled in Rochester, New York.

The Bayliss family was reasonably well-off, and Sarah was fortunate to be among the few women at the time who became well-educated and went to college. She became Sarah Royce in May of 1845, when she married a slightly older man, who was also British-born. They remained in Rochester for three years, but then decided to set out for more sparsely settled Western land. That land, of course, had long been claimed by Native Americans, whose concepts of “land ownership” and “settlement” were more than a little at odds with the ideas of Euro-American whites.

By early 1849, Sarah Royce and her husband Josiah were living in a small community about three miles from Tipton, Iowa, 60 miles west of the Mississippi River. There had been a flurry of rumors about the abundance of unclaimed land in California. The Royces had also heard that gold was found at Sutter’s Creek (now Sutter Creek), about 45 miles east of Sacramento. They soon joined the ranks of those who were called the “Forty-Niners” because in 1849 they packed their essential belongings in covered wagons and all but blindly headed west.

The Royces left Iowa on the last day of April that year. They traveled with other wagons as a rule. But it was difficult to keep up, in part because Sarah was unwaveringly religious, a strict adherent of a sect called the Disciples of Christ. She insisted on resting on the Sabbath, with the result that she and her husband (with a two-year-old daughter) sometimes lost sight of the wagons ahead.

The immensity of their journey from Iowa to California, powered by three yokes of oxen, soon became apparent. It took them an entire day to reach the town of Tipton, having traveled only three miles. It then required another week (including inert Sundays) to reach Iowa City, from where they headed further west. While passing through Fort Des Moines, they were warned of an outbreak of cholera in Council Bluffs, but they pressed on regardless.

Arriving at Council Bluffs by early June, they found a “city of wagons,” all of which were waiting in line to be ferried across the “turbid and unfriendly” Missouri River. It was there that they also encountered Native Americans: “You could not give them anything—giving a thing to one would bring a dozen more to you. You had to keep them at a distance—not be friendly.” They would have later encounters with such “hostiles,” but the real threats to their lives would come from the diseases that they themselves were transporting in their bodies: scarlet fever, cholera, small pox, measles, tuberculosis, and others.

It was late in the travel season, and the Royces were among the last to cross the Missouri River. They would need to travel doggedly in order to pass through the mountains before the winter snows began. Still, Sarah insisted on resting on Sundays, while the other wagons moved ahead. They succeeded in crossing the Rockies, and soon after reached the Great Salt Lake. But hazardous travel loomed ahead. Fresh water was scarce, and the desert heat was so intense that they rested in shade during daylight, and traveled in the dark of night.

The pace of the near-starving oxen (some of whom perished) was so ponderous that Sarah walked alone ahead. In the darkness, she and the rest of her party failed to see a turn-off for a shortcut that would ensure their survival. At last, in desperation, having seen roadside evidence of victims of the same mistake, they turned back and retraced their steps. They succeeded in crossing the desert, the Carson River, and the Sierra Nevada mountains with the help of government scouts. At last, they reached Weaverville, in north central California (about 100 miles east of Eureka) in October 1849.

How do we know all this? I confess that I myself did not, until recently. But then I remembered a book I had read many years ago. Titled The James Family, by F.O. Matthiessen, it is a wonderfully rich account of the various interactions among the brothers William and Henry James, along with their parents and siblings.

William James is my favorite philosopher, and on page 422 of that book is an unforgettable pair of photographs. They show in sequence two snapshots of James, seated on an old stone wall at his summer farm in the White Mountains, near Chocorua, New Hampshire. Conversing, while seated beside him, is his likeable, younger friend, a philosophy colleague at Harvard, named Josiah Royce. As the camera clicked, the ever-joking James exclaimed, “Royce, you’re being photographed! Look out! I say Damn the Absolute!”

That Harvard professor, Josiah Royce, was the son of Sarah (Bayliss) Royce, who walked from Tipton, Iowa, to Weaverville, California. His father was Josiah Royce, Sr., of course. The younger Royce was born in 1855, and grew up in California. At some point, it was that same admiring son who persuaded his aging mother to share her candid diaries from that astonishing journey. Readily available now, they were published in 1932 as A Frontier Lady: Recollections of the Gold Rush and Early California (Yale University Press).

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, graphic designer, and retired university professor. Of late, he has been making short films on subjects related to art and design.