Recently, I was reading a Slate piece on artificial intelligence. Writers, after all, have been put on notice that our craft will soon be practiced to a greater or lesser extent by AI. Keeping tabs on the competition is always a good idea.

The Slate article included a link to another piece, this one from 2012, titled “The Android Head of Philip K. Dick” by Torie Bosch. The story centered on the book How to Build an Android: The True Story of Philip K. Dick’s Robotic Resurrection, a book by David F. Dufty.

I don’t know how I missed Dufty’s book when it was first published. I am a huge fan of Philip K. Dick’s often odd, frequently thorny (to the point of incoherence), and always fascinating science fiction novels and short stories and their ongoing impact on our culture. Dick’s 1968 work Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is the source material for Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner—which has risen from cult status to an ongoing franchise across comics, animé, and film. Dick penned the short stories that inspired the films Total Recall and Minority Report, and he wrote the novels that underpin the Amazon series The Man in the High Castle and the movie A Scanner Darkly.

I have an entire shelf devoted to beat- up paperback copies of Dick’s work (and books related to his work), and I think of my devotion to his oeuvre as the flipside of my Star Trek fandom. If Star Trek is built around a hopeful future and dreams of utopia, Dick’s work is built around paranoia and predictions of dystopia. Both, I might argue, wrestle with questions of what it means to be human—and both employ androids to good effect to explore this question.

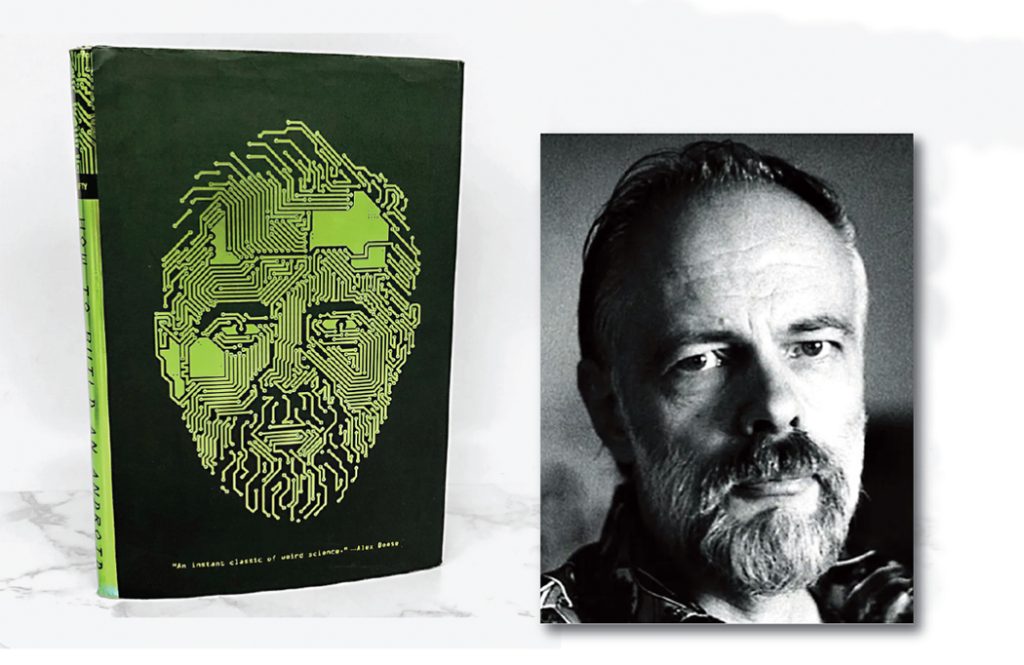

It perhaps goes without saying that I could not possibly resist a book about the creation of an android meant to emulate Philip K. Dick—even if I was a decade late. Within a matter of days, I had tracked down a copy of How to Build an Android, which sports a wonderfully evocative image of Dick’s face rendered in golden circuits and chips on its cover.

At the time of its publication, Dufty was recounting AI research and robotics craft at the cutting edge of both disciplines. Acknowledging the whimsy that undergirded efforts to recreate PKD (a frequently used abbreviation of Dick’s full name) as an android, the project was nevertheless exploring the outer limits of various technologies. Dufty shares this though technological challenges and breakthroughs in an accessible way, and they are fascinating to read now as we consider the recent advances in AI and robotics. Dufty also offers some insights into Dick’s work and why it might appeal to researchers in these areas.

But Dufty’s story isn’t merely one of technological derring-do. It is also a very human story of strong personalities, competing priorities, ambition, collaboration, setbacks (some humorous, some disheartening, and some that are both), and grit. The book also investigates how—or if—humans can be made to feel comfortable interacting with androids. That question is perhaps brought into sharpest relief by the decision (admittedly driven by tight deadlines as much as philosophical inquiry) to leave the back of the PKD android’s head open so visitors could see the inner workings. That peek inside stands in contrast to the painstaking efforts to make the android look, sound, and interact with interlocutors just as the author himself did.

How to Build an Android, like the most engaging and thought-provoking of Dick’s works, invites readers into a pretty far-out dream that reveals more than might be expected about reality.

*Quote from Alex Boese, author of Elephants on Acid and Electrified Sheep