August. Its mere utterance brings a flutter of anxiety. It’s a word that’s been permanently imprinted with the back-to-school scaries.

August was that hot month when, as a kid, you were struck hourly by the urgent need to eke out summer’s remains before they whirlpooled right down the drain. Soon you’d be careening into the sticky spirals of social angst, the endless laundry cycles of an incurably smelly school uniform, and burdensome piles of incoming history homework. In August, the panic of imminent responsibility would rise in your throat as you took careful stock of how many days in a row you’d just wasted playing solitaire on the velour family-room ottoman. With a shaking, sweaty finger, you’d trace a message across the velvety fibers, “End of summer, S-O-S,” but seconds later wipe it away to deal yourself yet another hand.

•••

In 1980-something August, our final opportunities to fart around at the outdoor O.B. Nelson Park public swimming pool felt depressingly near. Close at hand were our last chances to “free swim” in the deep end, a late-afternoon ritual wherein muscular lady lifeguards in high-cut Speedos would allow us—a handful of proudly certified deep-enders (a.k.a. the children who could actually swim)—to test the limits of our curbside diving skills, our strained chlorine-shot eyeballs, and our young lungs as we dove for some other kid’s quarters. A handful of sparkling precious metals teased us from the aquatic depths under a pair of diving boards in waters so deep they remained untainted by the inevitable fog of kid pee and sloughed-off sunscreen. Free swim. An American institution.

•••

In August, the local soft-serve Dairy Bar was threatening to shutter up again for the season. Goodbye to crunch-top twist cones. Goodbye to the sensation of that sweet, sweet Nectar of the Gods trickling down your forearms and dripping off the tips of your elbows. Goodbye to the insects loudly meeting their ends in the zapper above your head as you endeavored to shove the stump of a soggy wafer-cone into your mouth before it entirely lost its integrity and its contents onto your shorts—a factor that would decide whether or not you’d be allowed back into the family car.

In August, the strained and warping tune of the town ice cream truck—our second favorite source for cold sugar—would soon be fading away for what felt like an eternity, akin to a funeral procession headed for the graveyard. A nine-month graveyard, anyway. For our family, it really was best that the truck leave us for the season. Over the course of a hot July, we kids managed to fully deplete my father’s dresser-top stash of spare change. His end-of-day pocket coins mysteriously evaporated in the sun of our desperation; repeated grabs for pairs of quarters were followed by barefoot runs down the block to locate the truck wailing its circusy tune—never out of earshot but always somehow just out of sight. Our kingdom for a 50-cent ice-cream sandwich. Cool vanilla and a cakey chocolate exterior that you’d eventually have to scrape off your fingers with your teeth meant a chance to break up the agony of delicious summertime boredom.

•••

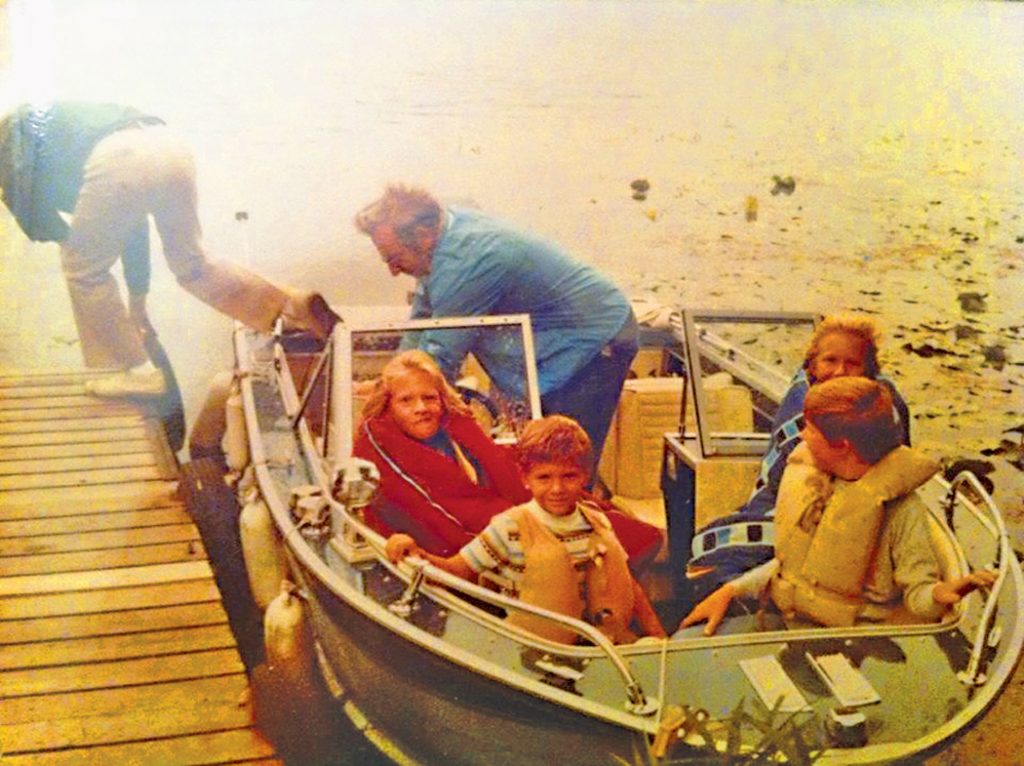

In August, final vacation days would be occasionally siphoned off for a family trip to see relatives in Wisconsin, the state in which we’d bury our cousins, to the neck, in the sands of some lazy northern lake, or relearn how to not choke on brown water while being pulled behind Grandpa’s motorboat via various user-unfriendly crafts. Only once did I almost lose a finger in the tightening tangles of a quickly tautening rope behind a boat. Only once did Dad break his ribs crashing down from Uncle Dean’s skis onto rock-hard water. Only once was I allowed to steer a motorized boat on Black Bear Lake.

In my defense, I was trying to create an amusement park of waves for us to ride by cruising back through a jungle of my own wake waters, like I’d seen Grandpa do countless times for cheap thrills. And family fun. But I took it too far. We almost lost Ma that day over the bow. I was not allowed anywhere near the tiller after that.

•••

There were Augusts so hot in my memories that Dad, broke as he was, finally turned on the air conditioning. Augusts so hot that all we could do was rent a VCR for the day, eat ice cream out of a box all afternoon, and watch the entire series of Poltergeist movies. “Runnnn to the light, Carol Annnnne!”

On steamy August nights, after our enforced family “lights out” time, I’d sneak a book to the screen window of my bedroom and decipher a whole chapter or two by the light of the crazy-bright softball field across Filmore Avenue. Always a mournful moment when the game wrapped up and they cut the power on Emily of New Moon.

•••

There were also Augusts my younger-by-two-years brother Noah and I spent playing board games in a hand-me-down camper tent on wheels, parked in our own backyard. We’d actually be allowed to spend the night in that mildewy thing, though it was by no means to be trusted in a thunderstorm. Out there, hidden from parental view behind a thick hedge, I burned through Little House on the Prairie via flashlight. Scandalous.

•••

One August night when we were a bit older, Noah and I snuck out of that same camper to roam the town. A wasted opportunity perhaps, but upon our clean exit from the neighborhood under the cover of night, the only thing we could think to do was visit the apartment of our own college-age sibling, Abram, who was and still is just as bad as we were at thinking up ways to get into trouble. The three of us parked ourselves under a large tree on the Fairfield town square and sat and talked, about nothing and about everything, until we got tired and just went home to bed. I like to think our parents might be proud at how little mischief we actually got up to even at the very pinnacle of our rebellious years.

•••

My favorite August memory drifts back to me from the night before I left for college. Back-to-school dread was replaced that evening by the buoyancy of impending semi-adulthood, by happy crickets singing their lungs out under the stars, and by the intoxicating attention of a boy. Thomas Garvey picked me up down the block from my parents’ house at the appointed hour—midnight—and drove me wordlessly down dark gravel roads to the local quarry, where he proceeded to not lay a single finger on me. Instead, he respectfully showed me how to not kill myself leaping off a rope swing into water by the light of the August moon.