From the Iowa Source archives, August 1998. The 50-year-old museum was completed remodeled in 2021.

The Theatre Museum of Repertoire Americana houses one of Iowa’s better kept secrets. The unassuming building at 405 E. Threshers Road, Mt. Pleasant, provides a home for one of the largest collections of memorabilia from an almost-forgotten era of entertainment. Spanning the late 1800s to the mid-1900s, the phenomenon of “Repertoire Theatre,” as it was then called, spread west across rural America, leaving few towns untouched by its magic. Now virtually unknown, these traveling dramas, comedies, mysteries, and farces burgeoned into one of the most unique and popular entertainment forms of its time.

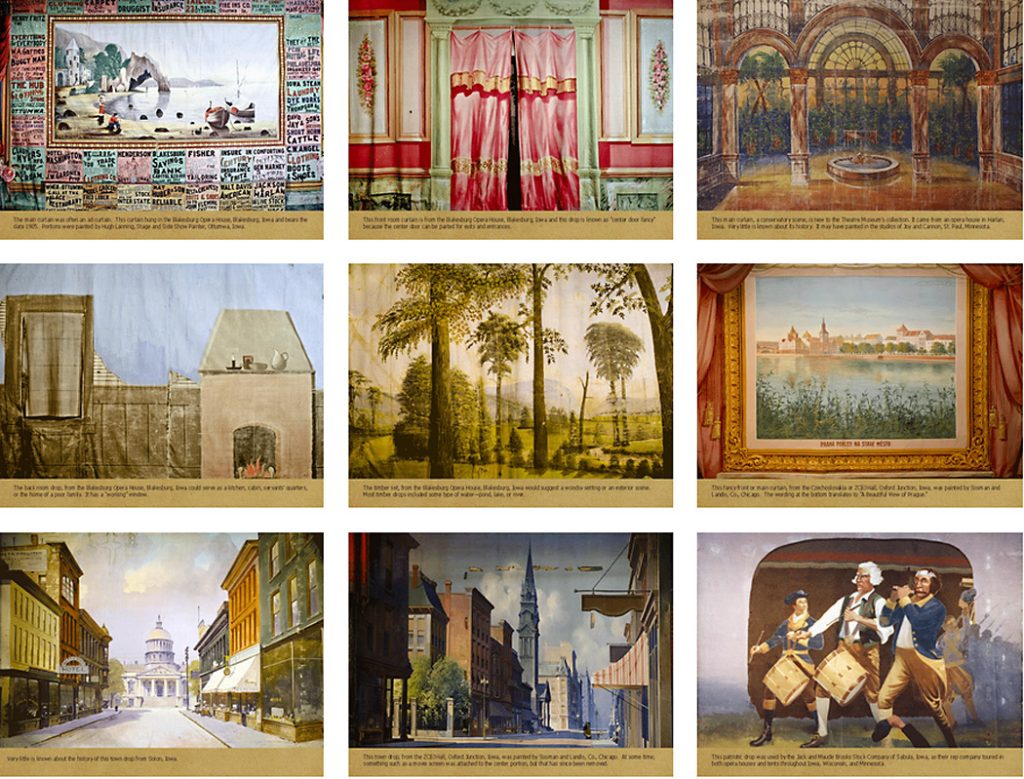

The Theatre Museum of Repertoire Americana invites the visitor to take a deep breath. No moving pictures, no televisions, none of our modern-day technology disturbs the moment. The room encapsulates the life and feelings of an era. A show herald, browned from years of display, advertises an upcoming play, Fine Feathers (“The biggest American play ever written”), set curtains display vivid scenes, and old tintypes and photos capture the image of a soliloquy from long ago and transport the viewer to this era in American Repertoire Theatre.

As Repertoire spread across the frontier, it took a special hold on Iowa, which by the early 1900s had built more theater houses than any other state. Many well-known entertainers passed through; some even made Iowa their home, such entertainers as the Schaffner Players, the Hila Morgan Show, the Jack and Maude Brooks Stock Company, the George Sweet Players, and Jesse Cox. If these are not household names now, 70 years ago they were as familiar as Tom Cruise or Gwyneth Paltrow are today.

Repertoire’s Enormous Popularity

Despite inconveniences and insurmountable difficulties, Repertoire Theatre spread across the nation like a wildfire. It spread despite the hardships and, often times, the impossibility of travel. It spread despite the inconveniences and discomforts of daily living. And it spread despite repressive, puritanical attitudes.

In the earliest years of Rep Theatre, steamboats floated productions up and down the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Stopping in towns along the way, theater people staged their productions—Shakespeare and the popular minstrel shows. Even circuses performed from these showboats.

“The boats sometimes stopped in wooded areas where there seemed to be no sign of civilization at all,” says Martha Hayes, Collections Supervisor of the Theatre Museum. “Just the river flowing along as it had for hundreds of years, trees lining the banks, and birds singing. Someone on board sounded the calliope, and soon enough, people poured from the woods to see a play.”

Early steamboats were often crude affairs. Boilers exploded, setting fires on board, the vessels snagged and sank along the riverways, but eventually safety improved, and the boats plied the rivers, often in regal style. A 1853 excerpt from Hunt’s Magazine states:

The word “boat” gives a very imperfect idea of this floating palace, which accommodates . . . from five to six hundred American citizens and others of all classes, in a style of splendor that Cleopatra herself might envy . . . . I followed a crowd of 500 up a handsome staircase, through splendidly furnished saloons covered with carpet of velvet pile, to the upper deck. Tea being served, we all adjourned to the gentlemen’s cabin. . . . At the entrance we were met by tall swarthy figures, clothed in white linen of unspotted purity, who conducted us to our seats. There were three tables, the entire length of the room covered with everything that was beautiful.

Enduring Land Travel

But showboats were limited to the rivers. Actors, feeling the call, set foot to the open road. Their endurance, fortitude, and persistence proved heroic. In the early days, a few well-traveled roads, in heavily populated areas, were roughly paved with cobblestones or macadam, if paved at all. However, once out of city limits many thoroughfares were indistinguishable from the terrain. Travelways were seldom marked, or even mapped. Our ancestors would have reveled at a rough-tarred road with a few simple signs, or a map to help find their way. Instead, these trail-blazing thespians resorted to crude yet ingenious methods.

Gil Robinson’s memoirs, as quoted in Jere Mickel’s Footlights on the Prairie (North Star Press), describe a travel technique used after the Civil War until the 1900s. “A wagon sent ahead as a scout. Whenever a crossroad was encountered the driver would get out, pull down a rail from a fence, and lay it on the road pointed in the right direction.”

Wagons often sank wheel deep in rain-soaked mud, organ-crunching stagecoach rides on rutted roads bounced along at a snail-paced nine miles-per-hour, and walking left travelers weary and hungry. If the actors managed to find their way, soaking rains often turned roads into muddy quagmires, which held a new set of perils when a blazing sun baked them into rutted concrete slabs. Traveling over rain-drenched terrain in a horse and wagon could turn into a bivouac that would challenge a fit army. These difficulties lent new meaning to the phrase “the show must go on.”

Toward the end of the 18th century locomotives steamed across the country and actors traveled more extensively and more comfortably by rail. Yet, despite the iron horse, many troupers still relied on the four-legged variety, or they walked.

Other Occupational Hazards

Travel rigors were not the only inconveniences actors endured. Edison, in 1878, began a commercial enterprise with the incandescent lamp, but many towns, well into the 1900s, still used more dangerous forms of lighting—kerosene and gasoline lamps and torches. Actors and audiences took great care not to let a stray hair or piece of fabric too near the torches lighting the stages.

Actors riddled their way across the frontier despite the lack of suitable heating for frozen limbs, electricity to study scripts, or modern plumbing for hot baths. Though on occasion a hot bath might have been available, washing from cold-water basins was more routine, quite a feat for people who adhered to elegant dress codes.

In the Theatre Museum sits a make-up table nailed together with rough wood. Various tubes of Max Factor face creams litter the top. It conjures up a scene from years ago: A cold breeze rustles through the backstage dressing area. An actress dabs her face with cold water, then applies make-up for her first scene. She presses cold fingers to her cheeks and rubs rouge in a rounded motion. She shivers, takes two deep breaths, then rubs her arms before slipping into a silk dress, cold like the room.

Moral Opposition

Perhaps most significant, traveling theater burgeoned despite puritan attitudes, convictions that affected the ethical and moral codes of many settlers, and should have stopped the thespians in their tracks. The colonies had attracted people seeking religious freedom—Puritans and Calvinists whose tenets settled in the nation’s consciousness. These attitudes spread west along with the Protestant faiths.

Early Puritans felt theater held no place in the scheme of things, and though their numbers were diluted by later settlers, the attitude prevailed that theater was disreputable. From a certain perspective it might have seemed that way. Actors roved from town to town as they pursued their trade, they held “no good, steady work,” and, it was felt, they held a loose rein on their morals. While now and then this may have been the case, soon enough Repertoire managers became very conscious of the company’s image.

By the late 19th century the religious taboos of the early settlers had relaxed. The country attracted more and more settlers, no longer immigrating strictly for religious reasons. Pioneers moved steadily westward, settling in isolated hamlets with little entertainment other than the Sunday service, spelling bee, or what was self-furnished. People were eager for some diversion from the monotony and grind of daily chores and an often solitary, lonely existence. This 1915 United States Department of Agriculture report relates the following heartfelt request:

“The only thing in which I see much room for improvement (in farm living) is in a social way, and just how this is to be accomplished is a question. With the disappearance of the spelling bees and literary society, it seems that all social affairs have practically ceased, and the farmers have not been together as in former years. The average farm homes in the . . . valley (even granting such homes have modern conveniences, pianos, etc.) are prisons: the women, prisoners—“trustees,” of course, but nevertheless prisoners—made by such circumstances over which they have no control, or better perhaps by environment. We are starving for social conditions, pleasurable hours. . . . We want entertainment and life just the same as city dwellers.”

And the Troupers Brought Entertainment

A bowler hat sits on a shelf in the Theatre Museum, looking as trim and neat as when an actor tipped it at a passing admirer 90 years ago. The troupe arrives at the station. It’s been a long, sweltering train ride, but they parade through the dusty streets, the men dressed in their best suits and the ladies in their finest silks and frills, not showing a wrinkle.

Many town folk dressed in rough, country clothing, suitable for long hours at the till and the cooking stove, but Repertoire managers, well aware of delicate public opinions, often insisted on an impeccable dress code. Actors dressed elegantly, assembling extensive wardrobes that none but the rich could afford. Society women and men, much as today, often retired their apparel after a single wearing. These once-worn items were often turned in to second-hand shops, then sold to the actors at a reduced price.

Since Repertoire Theatre was dependent on its acceptance and popularity, certain codes of dress and especially behavior were required by the managers. A small slip or transgression could have dire consequences for a company dependent on its good image. Managers often preferred hiring families; they held less potential risk than a handsome single man or an enchanting leading lady.

The actors’ elegant and romantic appeal certainly aided their popularity, but these thespians needed more. Repertoire actors required numerous skills. They memorized five to six scripts a week, a talent which required a rare, photographic mind; they danced and sang in the between-scenes variety acts or vaudeville sketches; they played in the band prior to the performance. Explains Martha Hayes, “A question usually asked in stage interviews, ‘Can you double in brass?’ meant, ‘Are you a jack of all trades? Can you play an instrument, sing, dance, and, most important of all, can you memorize six scripts a week or portray two or three characters in a play?’ And when labor was in short supply, during the world wars and hard times, the actors, both men and women, frequently helped out with production set-ups.”

Town people came to know and idolize the actors for their talent and appeal, but there were other reasons for Repertoire Theatre’s popularity. The companies, first and foremost, held a careful finger on the public’s pulse. Repertoire companies performed for the rural communities, which had little in common with big-city folk and in turn with the kinds of dramas and comedies produced in Boston or New York.

The Plays

Shakespeare, Chekov, or Racine might not have provided plots, characters, or language rural audiences could readily identify with. As a result, many plays were written or adapted with rural audiences in mind, the faster writers turning out absorbing scripts by the numbers. Jere Mickel, in Footlights on the Prairie, relates:

The characters seem to be two types: the greedy and dishonest banker, and his sycophant, the old maid gossip of the town; the minister, and his wife, too much possessed by her importance as the minister’s wife; his brother who has seen something of the world, and the two young people, the sister-in-law and her sweetheart. All of them have the elements of real characterization. They seem so convincing that even sophisticated audience members leave the theater saying, “You know, I know somebody just exactly like that!”

To draw their audiences, writers sometimes used suggestive titles (Natalie Needs a Nightie, Three to a Bed, or Right Bed Wrong Husband), an odd and somewhat quirky twist, but the play’s content had to be squeaky clean, beyond reproach. “The writing and acting of Repertoire Theatre had to provide good, clean family fun,” says Donna Stender, the Museum’s Public Relations Coordinator, “and it had to grab and hold audience attention.”

Of one popular play, Saintly Hypocrites and Honest Sinners, Jere Mickel commented, “When read, the play seems to be written in diction too stilted, flowery, and old-fashioned to be spoken in any kind of conversational style. When played, one sits back in honest wonder at how well the play works its effect on the audience.”

Out of the effort to produce plays reflecting the audience’s likes and dislikes, two widely popular folk heroes appeared—Toby, possibly originally a Shakespearean character, and later Susie, his counterpart. Toby, who appeared as a freckle-faced, redheaded farm boy in the Midwest and as a cowboy in the Southwest, bungled in and out of comic situations, but in most cases he was endowed with an honest heart and a native wisdom that always won out over the villain—often a corrupt rich person or big-city type.

Opera Houses That Never Housed an Opera

Developing appealing characters and riveting plays, the troupers worked hard to bring their productions to the frontier. The pioneers worked just as eagerly to accommodate them. Almost as soon as a group of people called themselves a town, they built a structure for entertainment.

A photo of an ornate theater hangs on the Theatre Museum wall. It brings to mind some grand Florentine opera house. Three tiered balconies decorated with flourishes and flounces appear to float in mid-air, nestling throngs of people listening attentively. The photo conjures up images of a Mozart or Verdi opera in a European city. But this is no Italian or Austrian opera house. This photo depicts an opera house very much like the theaters that cropped up in rural and prairie towns across the U.S. frontier.

Most surprising of all is the sheer number of opera houses built in rural America. In their book, The Opera Houses of Iowa, authors George D. Glenn and Richard Poole state that in Iowa alone “more than 300 such structures still stand and we estimate that four times that many originally existed.”

Opera houses sprang up one or two to a village. These structures provided a place for quilting bees, meetings, graduations, dances, and musical events, but ultimately they provided a stage for the Repertoire companies. The houses added a sense of prestige and civilization to the town’s self-image.

“The buildings sprang up in a variety of styles and sizes,” says Donna Stender. “Many were simple halls constructed over a town business—just a long room with a platform built to accommodate theater productions.”

Towns eager to commit more cash built theaters with varying degrees of grandeur, depending on the town’s needs or desires, and apparently not having anything to do with the town’s size. Some of the smallest towns in Iowa built the largest houses. As early as 1893, What Cheer erected a grand, three-story opera house with dressing rooms and a 24-foot proscenium. Like today, in 1893 What Cheer was a town of just a few hundred folks, yet the theater seated 850 people!

A Clever Euphemism

Grand or modest, opera houses spread across the nation as fast as the troupers. Though religious taboos had relaxed enough for this growth spurt, the word “theater” still left a bitter taste in the mouths of religious leaders. The Opera Houses of Iowa states the following about early American opinions:

“Although theatre was welcomed in some parts of America in the 18th century, particularly in the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies (and states), authorities in other areas such as New England and Quaker-dominated Philadelphia frowned on theatre as an immoral activity, and prohibited it whenever they could. Theatre managers and performers cleverly circumvented the restrictions with a number of subterfuges. Plays were disguised as something else: A performance of Othello, for example, would be advertised as a ‘Moral Dialogue on the Effects of Jealousy, in Five Parts.’ And the performance space was disguised by calling it a ‘Museum,,’ an ‘Academy of Music,’ an ‘Athenaeum, ‘or ultimately, an ‘Opera House.'”

The term “theater” was not acceptable, but, as Jere Mickel relates, music was acceptable: “Music had for centuries been a respectable art as it had always been associated with the worship of God. Opera is music.” Since music was performed in opera houses, that term was selected as a euphemism for theater, though neither Mozart nor Verdi may ever have been heard in their halls.

Portable Tent Theaters

Just as the term “opera house” suggests an opera, a large tent conjures up images of a circus or revival. A tent probably would not conjure up images of a full-scale theater production. Many may never have heard the term “tent theater,” yet these huge canvas structures crisscrossed the frontier, traveling from town to town throughout much of the year.

Originally used primarily for revival meetings, tent shows sprang up in the late 19th century in the warm-weather South, then spread north in spring and summer months. Tent Repertoire experienced a growth of popularity when silent films and sweltering summers invaded the opera houses. In a stroke of ingenuity, the production companies brought theater to the townfolk—large canvas tents erected and taken apart, usually in the span of a week. The companies traveled by train, sometimes by horse and wagon, carting along everything from the strapping canvas tents to props, curtains, wardrobes, scripts, and the family—Repertoire Theatre companies were often family affairs.

These tents were another testament to the popularity of Repertoire Theatre, and another aspect of our ancestors’ flexibility and ingenuity. Tents proved, on the one hand, arduously portable, yet portable. The productions drew huge crowds, seating 200 to 2,000 people, larger audiences than many opera houses packed in. The New York Times in 1927 estimated that 400 tent theater companies had visited 16,000 communities and played to 76,800,000 people.

These overflowing crowds generated large profits, but large crowds were never guaranteed, so production companies hired and relied on savvy advance people. Pre-show ad preparations rivaled the work of any Madison Avenue executive. These agents traveled ahead of the production crew, scouted their area, found a lot for the show, mixed with local business people, and plastered the town with ads, often hiring a young boy to do the job in exchange for tickets to the play. Any ploy that worked and was accepted by the audience became a successful means of advertising. Candy box sales, with prizes and coupons inserted, became a favorite gimmick, and hawking the confection became an art form that evolved some very unique pitches. Harley Sadler, a well-known Repertoire actor and manager from the Southwest, used this pitch (from Footlights):

“You never can tell what you will get out of this candy. Two years ago, a boy and a girl found prize coupons in their candy. The boy’s called for a pair of ladies’ hose, and the girl’s for a safety razor. I suggested they exchange prizes, and they did. That was how they met. They got married, and last night, they came to the show. With them was a bouncing baby boy. As I said, you never can tell what you will get out of this candy.”

Props, Scenes, Curtains, and Other Cumbersome Things to Cart Around

In addition to hauling around stadium-sized tents, Repertoire Theatre companies also transported their own props and scenery. Early stages relied on painted backdrops or curtains and wings. The wings, canvas-covered flats, were painted in keeping with the stage scene and positioned along the stage sides, closing off the actors’ dressing area. “This is where the actors changed and waited for their cues, or often with a difficult script, sneaked back stage to have a quick look,” says Martha Hayes, “thus the familiar expressions ‘waiting in the wings’ and ‘winging it.’ ”

At the back of the stage hung a wall-sized curtain, (about 12 by 25 feet) depicting the appropriate scene for the performance. This backdrop provided the all-important main focal point. It drew audience attention into the show. In one picture, the curtain scene conveyed the mood and tone of the play. It was the best means available. However, this important stage prop caused its share of problems, too. The painting methods left coats on the canvas which cracked and peeled easily. When transported in railroad baggage cars, the wings alone required large spaces, but the curtains proved even more problematic. Since they couldn’t be folded, they were packed flat in large crates. These crates were difficult to handle during shipping and moving, and they took up more than their share of the freight storage areas. While larger, wealthier companies transported their own scenery and curtains, many companies simply couldn’t afford the extra expense.

“Smaller companies relied on the scenery provided by the local opera houses,” says Donna Stender. “These facilities often supplied standard curtain scenes, so standard they became commonly known in the trade as ‘front room,’ ‘back room,’ ‘timber,’ and ‘town.’ A front room curtain might represent a posh parlor or living area used for palace, mansion, or wealthy settings. A back room scene might represent a kitchen, cabin, servants’ quarters, or poor family home. Timber curtains depicted a bucolic or wooded setting used for outside scenes and often included a body of water—river, lake, or stream. The town curtain represented a city street or square.”

While the backdrop scenes may have been fresh and interesting when new, these curtains probably grew tiresome when viewed year after year, especially when the paint cracked and flaked.

An Ingenious Iowan to the Rescue

If the logistics of theater proved difficult over the years, technology came to the rescue in a few cases. Railroad mileage aided the troupers’ travel, but another leg-up came from an unlikely source. It came from an Esterville, Iowan who revolutionized theater production in a unique way.

Born in Illinois, Jesse Cox moved to Iowa in 1891. Enamored with theater at an early age, Cox began his career as a prop boy, and as a teen he joined the Warren G. Noble Dramatic Shows of Chariton. The young man subsequently worked with a number of companies, and like many actors of his time, developed numerous theater skills. He worked with scenery and props, acted, and played in the band. He later owned, edited, and published The Opera House Reporter, a weekly show business newspaper. Cox also painted scenery and curtains for a local opera house. This skill in particular left him thoroughly familiar with their cracking and flaking problems. Cox experimented and, as a result, revolutionized theater production in the process.

He developed a technique called Diamond Dye painting, which used dyes instead of paints to change the color of the cloth. This approach involved using a household dye called Diamond Dye, commonly used by women to color clothing. Cox developed a method of heating a glue and applying it as a kind of sizing that accepted his dyes. He used unique short-haired, soft bristle brushes, which gave him more control over the dye application.

In a corner of the Theatre Museum sits a sturdy, wooden work table covered with paint drops and smudges. The table is lined with enamel containers, each one filled with vibrant dyes—bright sun yellow, ruby red, violet, green, ocean blue. A faint paint smell hangs over the work table, and it almost seems that Cox works nearby.

Cox’s special technique meant the curtains could be easily folded and transported without cracking the paint. With this advanced technology at his fingertips, Cox was also able to produce far more brilliant, colorful curtains than the four standard scenes. At its peak, his business sold thousands of yards each month, nationally and internationally.

The End of Repertoire

It is perhaps a little sad that Repertoire Theatre is no longer a household word. Once popular, widespread, and personal, these plays represented their times. Today’s actors might actually meet very few fans, but Repertoire Theatre people knew their audiences well enough to reflect their emotions, character, and tastes. Now theater historians are rediscovering these plays as a body of literature worthy of study. Not profound, earthshaking, or epic in nature, the literature, nevertheless, tells the story of an age and of a people, whose likes and dislikes were scribed so neatly in the scripts played for them.

The period spans roughly 100 years. Monumental innovations and changes occurred: a depression, two world wars, electricity, the car, and an industrial revolution. All of these changes made each Rep Theatre decade somewhat unique, but none of the changes proved as drastic as the advent of celluloid and television, which laid this period to rest in museums.

As we glide into the year 2000 and turn over yet another century, with all our attendant technology, with our cell phones, computers, and cyberspace, we move closer to the characters in an Asimov novel, whose only contact with humanity is through holograms. We seem so distant from our 19th century ancestors who interacted only with live audiences. Through a long telescope, we peer beyond at the actors, at the characters they created, at their scripts, but can only view them minutely through the photos, memorabilia, scrapbooks, and stories left behind in this Theatre Museum. We can only piece together their existence.

Their lives obeyed rules different from ours. They intrigue us with the difficulties and inconveniences they surmounted and the ingenuity they mustered to reach for their goals. They intrigue us with their personal touch. We often wonder, how did they do it?

These Repertoire Theatre people were actors, who wanted above all else to act for audiences who craved entertainment. This bond formed a mutual attraction or symbiosis. Perhaps more than any other ingredient, it was this bond which generated the traveling theater phenomenon, despite the difficulties and seeming impossibility of it all.

The Role of The Schaffners

That this period of Repertoire Theatre is remembered, brought to the spotlight again, and studied in Mt. Pleasant’s Iowa Theatre Museum is a tribute to Neil and Caroline Schaffner. Respected and popular entertainers for years, the Schaffners began their career at the turn of the century. They were born at the right time to fit neatly into the golden days of American Repertoire Theatre.

Neil Schaffner began his theater days as a young boy in Fort Dodge, Iowa. In his book, Toby and Me, Schaffner wrote that he loved anything to do with theater. He met Caroline Helen Hannah while she was touring with Al Russell and His Sizzling Cuties in Schaffner’s hometown. Though they began life separately, it seems these two stars were literally crossed; they were destined to meet and become not only partners in marriage, but partners in acting, and partners in one of the most successful and long-lasting production companies, which they passed on to the late Jimmy Davis in 1962. No mean feat when most companies had been replaced by movies and television.

Many older Iowans may remember the Schaffners’ Toby and Susie portrayals and radio show. “But there was much more to the Schaffners,” says Martha Hayes, as she pulls up information on her computer screen. Martha reads aloud, “The Schaffners appeared together in over 300 plays, giving around 5,000 performances, playing to 100,000 paid admissions per summer season. That’s probably more acting than a roomful of popular movie stars put together. Not only did they act in and manage their own company, the Schaffner Players, they also wrote over 40 plays and adapted over 100 others.”

Toward the end of their career, the Schaffners recognized something that few others saw; they recognized that the opera houses and tents were no longer filling up. When they realized audiences no longer flocked to tent productions, they began collecting and saving theater memorabilia, whenever there was an opportunity.

New Beginnings

The seed idea for a museum sprang to life when Neil and Caroline Schaffner began collecting artifacts. The Theatre Museum of Repertoire Americana itself sprang to life when the Mt. Pleasant community, one of the few communities in the U.S. to do so, worked together to organize funds for a permanent home and building for these precious artifacts. A recent grant from the Iowa Community Cultural Grant program, administered by the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, provides funding for five part-time staffers. The Theatre Museum may still be one of Iowa’s better kept secrets, but the subject matter is a carefully tended treasure, nurtured by the staff and volunteers. Twenty-five years ago, this dedicated group launched an effort to bring this fascinating period to light. To date they’ve worked tirelessly, building and maintaining one of the largest Repertoire Theatre museums.

Their success is demonstrated in the museum building. It houses a rich and diverse collection of artifacts: stage drops, many from Iowa opera houses; scripts written during the Rep Theatre golden days; music scores; show heralds and playbills; costumes and scenery; photos, scrapbooks, diaries, and letters donated by troupers and their families; not to mention a sophisticated computer-catalogued library that stores, organizes, and cross-references reams of theater history data. These materials share this golden era of entertainment with visitors as well as dedicated scholars.

The Theatre Museum not only provides an extensive collection of exhibits, it also provides a number of educational and research opportunities. Scholars from around the country use the museum as a research resource. It also provides an outreach program for schools.

Annual Theatre History Seminar

Those interested in theater history and scholars alike are welcome to attend the Theatre Museum’s annual seminar. The weekend offers a wide variety of talks and papers from doctoral candidates and professors, as well as play excerpts. The event also provides an opportunity to hear former troupers share their times and experiences. For more information about the museum, the plays, or the seminar, call the Theatre Museum (319) 385-9432,.

Thanks to all the Theatre Museum staff and to Lennis Moore, Administrator and CEO, Midwest Old Settlers and Threshers, for offering time and information about this fascinating period. Thanks and credit goes to Richard Poole, who filled me in on details and graciously allowed me to use quotes from the book he and George D. Glenn authored, The Opera Houses of Iowa, published by Iowa State University Press; to Corinne Dwyer at North Star Press for allowing me to use quotes from Jere Mickel’s book, Footlights on the Prairie. And thank you, Karen Bates Chabel, for photos of the museum interior. My apologies for any information or details I might have inadvertently misconstrued about this vast, intriguing topic.