The technique of sandpainting is as old as the hills, in the sense that it has long been practiced by Navajo artists (using various colors of sand from their Southwest surroundings), Tibetan and Buddhist monks, and indigenous Australians.

In the second half of the 19th century, a curious variation emerged in eastern Iowa, in which designs with astonishing detail were made by arranging grains of colored sand from the bluffs of the Mississippi River. To construct anything using only grains of sand is painstaking—but in this case, the images were composed and tightly packed within glass jars designed for chemists. In ways, it was comparable to constructing a ship in a bottle, when building the ship would be challenge enough.

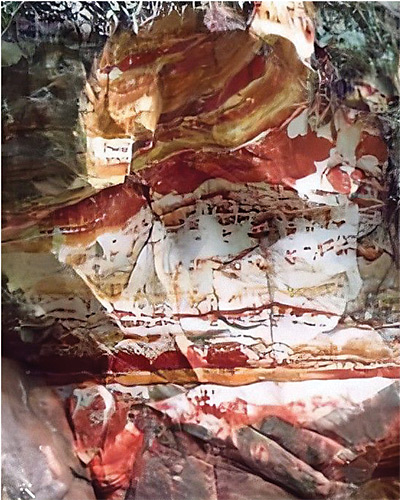

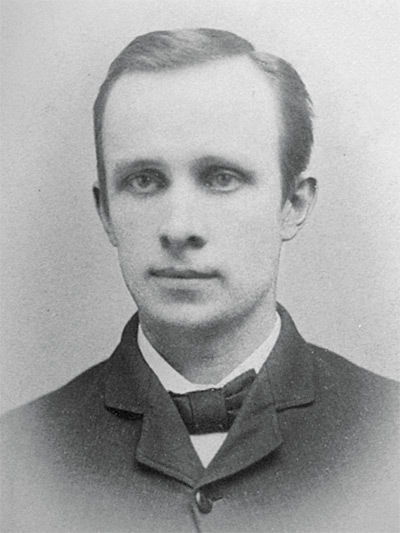

These sand art bottles were created between 1860 and 1894 by a self-taught folk artist from Iowa named Andrew Clemens. Born in 1857 in Dubuque, Clemens grew up in McGregor, Iowa, in the vicinity of Pikes Peak State Park, where there are breathtaking overlooks of the Mississippi River. At that site, there is a region of sandstone called Pictured Rocks, where the sand has been naturally colored by the slow, moist seepage of iron and other minerals. In some places, the colors have settled in one-color layers, while in others, they are (as described in a news story) “mottled and variegated most fantastically.”

As a youngster, Clemens was stricken with encephalitis, which impaired his speech and hearing. In keeping with terminology then, he was described as “deaf and dumb.” As a result, he spent his teenage years at the Iowa School for the Deaf in Council Bluffs, while returning home for summer breaks. It was during those summers that he became intensely interested in the colored sand deposits near McGregor. In 1877, when the school was closed because of a fire, he returned to his hometown and remained there for the rest of his life. The only exception was a brief period around 1889, when he worked in Chicago as a “curiosity” at a popular museum. There, he made sand bottle paintings while museum visitors looked on.

Clemens is usually said to have made hundreds of sand bottle paintings in the years before his early death in 1894. But those that survive are considerably fewer in number. To prevent any sand grains from shifting, the contents were extremely tightly packed and sealed at the top with a stopper and wax. Thus sealed, care was required in viewing the art. A bottle might easily shatter if dropped, or break if two bottles butted—in which case the sand streamed out, and the pattern inside was completely destroyed.

Clemens’s sandpaintings were sought after while he was still living and are even more coveted now (in a 2018 auction, one of his bottles sold for a record-breaking $132,000). They are rare in part because a complex commission might require as long as a year to complete. He was typically asked to make paintings that bore particular loved ones’ names or played up themes at a client’s request.

He was also beset by imitators, a few of whom had some success. But apparently no other artist was able to achieve Clemens’s accuracy, detail, and intricacy. Whereas his paintings might contain patriotic emblems, typographic components, ships, detailed architectural scenes, or even George Washington on horseback, those by other sand artists might be restricted to simple shapes.

One final bit of trivia: When you next find yourself engaged in conversation at a cocktail party, and the subject of sand art in bottles comes up, you will no doubt amaze your friends if you mention that its technical name is “potichomanie.” Good luck in pronouncing that: a double martini might actually help.

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, designer, and retired professor of graphic design. He teaches online courses for OLLI Drake at Drake University. For more information, see NorthernIowa.Academia.edu/RoyBehrens.