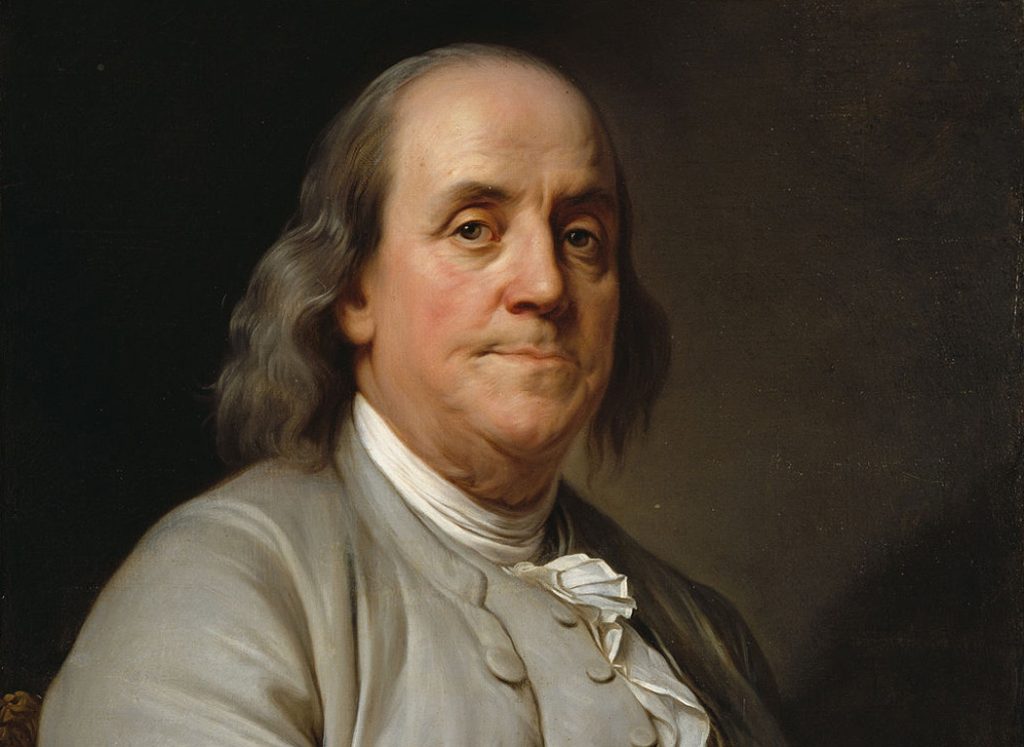

Our new Constitution is now established, everything seems to promise it will be durable; but in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes. —Benjamin Franklin

As Americans, we remember Benjamin Franklin as a Founding Father, a face on the $100 bill, and the man who flew his kite in a lightning storm. But as demonstrated by Ken Burns, documentary filmmaker extraordinaire, Benjamin Franklin was so much more. Burns reminds us that Franklin’s prominent political career developed in his later years, following a lifetime of lasting achievements that made him a worldwide celebrity.

Peter Coyote narrates this two-part, four-hour bounty of food for thought that aired on PBS and is now streaming on several platforms. Like all Burns documentaries, the lavish presentation immerses us in the social and historical perspective that brings the past back to life, while informing and entertaining even the indifferent viewer.

Since the camera wasn’t invented until after the 1700s (one of the few innovations Franklin didn’t create), Burns illustrates with richly detailed paintings. And Franklin shares some of his story through his own quotes (read by Mandy Patinkin), all seasoned with wisdom and humor. Several historians offer some added perspective, including Walter Isaacson, author of the 500-page biography Benjamin Franklin: An American Life. We follow Franklin’s amazing life from his Boston birth in 1706, as the 15th of 17 children, to his death in 1790 in Philadelphia, the city he mostly called home. All inseparably embedded in the context of America’s history, from British colonies to independence, of which Franklin was a crucial part.

Though his formal education was fleeting, Franklin proved to be his own best teacher, driven by his passion for books and research. He documented experiments with electricity; he charted temperature patterns of the Gulf Stream. He made practical inventions that improved or enriched people’s lives, like upgrading the printing press and creating the armonica, a musical instrument made of glass.

Talented, driven, curious, gracious, entertaining, wise, and financially successful, Franklin retired at age 42, when he decided to live “usefully” rather than being remembered as “a man who died rich.” He plunged into reading and research. And in Philadelphia and London, he thrived in the company of learned people, whose formal educations in the finest institutions did not dwarf Franklin’s intelligence, book knowledge, sophistication, and worldliness.

Franklin was so many people rolled into one: a scientist, an author and a humorist, a printer and publisher, a gifted communicator, and a successful businessman. He served as an ambassador and Postmaster General. He founded the first public library, and the nonsectarian Publik Academy of Philadelphia, which became the University of Pennsylvania. Franklin’s entire resumé reads like the accomplishments of a dozen gifted people.

And a remembrance of America’s most quoted statesman is incomplete without reviewing some axioms for all occasions: “There never was a good war or a bad peace.” “Love your enemies, for they tell you your faults.” “Three may keep a secret if two of them are dead.”

Franklin’s exclusive inventions include his world-famous lightning rod—inspired by his kite experiment—that continues to protect buildings and save lives. His understanding of positive and negative electrical charge led to his invention of the battery. And then there were his personal projects, like his unreachably high bookshelves that inspired the “Long Arm” grabber, a pole with a movable jaw. As well as his brother’s painful catheter that Franklin remade with a flexible tube, which is still the standard design.

Franklin’s love of practicality inspired him to optimize the function of existing systems. His famous Franklin stove re-framed the common wood stove in iron to generate more heat from less wood and with less smoke. As Postmaster General, he rerouted domestic mail within the colonies, eliminating the detour through London’s postal system and thereby shortening delivery time to one day. In his Ambassador years in Paris, he modified his spectacles to sharpen his vision both near and far. Bifocals are still popular today.

In a transcribed interview with Ken Burns on the PBS website, Burns says Franklin would have grasped the concept of our online public platforms because he was the one-man social media of his day. Franklin was the printer, the newspaper publisher, the producer of Poor Richard’s Almanac, and Philadelphia’s ground zero for news, ads, entertainment, and gossip. “He was Apple and Google and Twitter and Facebook, all in one.”

Here are some final takeaways. First: credit where credit is due. As ambassador to France during the war for independence, Franklin was a diplomatic maestro, patiently and persistently inspiring donations of desperately needed financial and military support for America’s military. Without the contributions of France and Franklin, the Patriots (Americans for independence) would have lost the war, and the 13 colonies would have remained the overtaxed, underserved subjects of the British Crown. And we would all be drinking tea instead of lattes and saying “ta-taa” instead of goodbye.

Second: did Franklin have flaws? I read somewhere that we all have them. And Franklin wouldn’t hesitate to show us his daily chart that tracked his shortcomings, which, he lamented, always surprised him. But would his fault list match ours? Well… Franklin owned several slaves. And he never considered freeing them, at least not until the drafting of the Constitution that emphasized equality and human rights. However, he and his wife sponsored the education of several slaves. And witnessing their strong academic growth made Franklin confront his racial biases and question where his assumptions came from. And what to do about them.

Another personal failure was that he abandoned his wife and daughter for years at a time, living a cultured life in London. Even when his wife got sick and died, Franklin failed to return for her funeral. These incongruities are impossible to reconcile in a social being who savored his relationships and improving people’s lives. Can one man be a beloved national hero as well as a disappointment? Apparently, yes. Confirming once again that people are complex, multifaceted, unfathomable creatures. The only closure is to surrender to the lack of closure and accept that human life is full of contradiction. Who will cast the first stone?

A final thought: the American victory freed us from an uncaring monarchy that was supposed to be serving all its subjects. So we designed our own government to represent and serve all its people. And now, 270 years later, how are we doing with that? Do our public servants put all their citizens first? It depends on who you ask. When socialite Elizabeth Willing Powel approached Franklin about the structure of our new government, she asked, “What did we get, a republic or a monarchy?” He replied: “A republic, if you can keep it.”