The American writer Gertrude Stein was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, across the river from Pittsburgh. She grew up in Oakland, California, a place about which she famously said, “When you go there, there is no there there.” She never set foot in Iowa. She didn’t even fly over—although she said she wanted to, but a snowstorm put a stop to that.

Nevertheless, as one reads her various books, it is tempting to conclude that she was well-acquainted with Iowa. Not only does she mention the state repeatedly, she also recommends it. In a cryptic observation, Stein describes Iowa as “gentle,” and claims—in ye olde spirit of Iowa nice—that “you are always well taken care of if you come from Iowa.”

The source of her ideas about Iowa are revealed in that very sentence. Having had no direct contact with the state, her opinions had been formed on the basis of what she had learned from her friends, at least two of whom were expatriate Iowans.

Who were those friends?

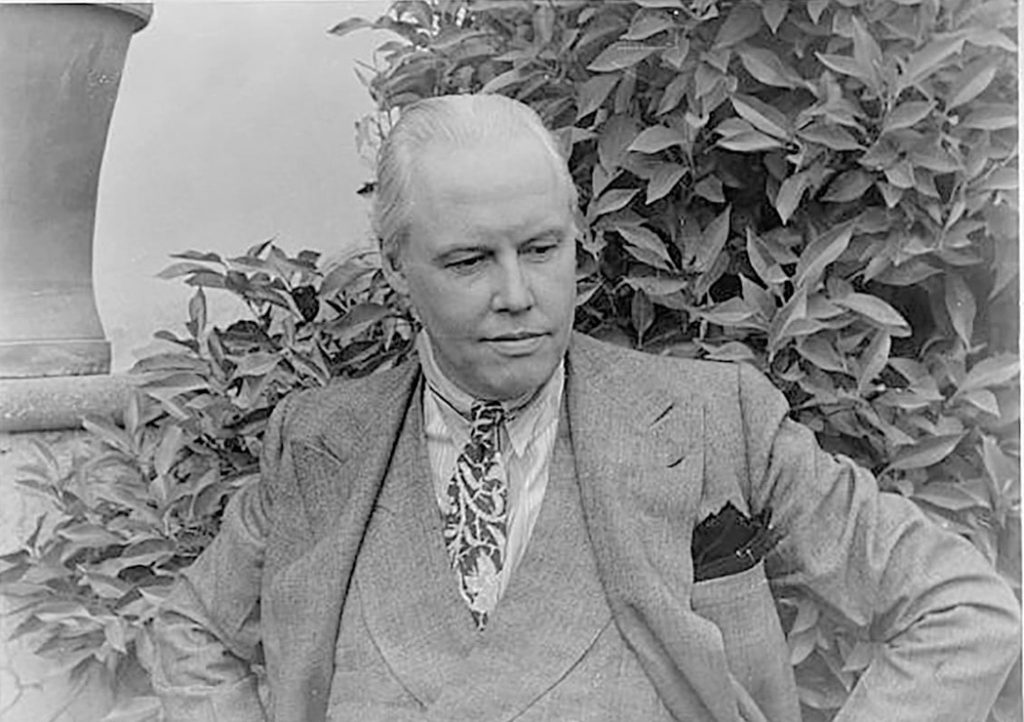

One was Carl Van Vechten, the American novelist, critic, and sometime photographer who grew up in Cedar Rapids. His father, Charles Van Vechten, was a prosperous local banker, and his mother, Ada Van Vechten, was central to the founding of that city’s public library. In southeast Cedar Rapids, one of the city’s largest recreational tracts is Van Vechten Park, which was made possible in part by Carl’s brother, Ralph.

As a young, aspiring writer, Carl Van Vechten grew disenchanted with his home city, a dilemma that was summed up by literary scholar Bruce Kellner (in Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decade) as follows: “Cedar Rapids was like one of its customary midday meals: wholesome and plentiful, unimaginatively but well cooked, on which one might grow. To stick around for second helpings, however, could only induce indigestion: the corn belt had a way of stealthily tightening around the belly.” Kellner concludes: “So he was born in Iowa, and he got out just as soon as possible” in 1899, at age 19, thereby escaping an “alien race.”

Van Vechten fled to Chicago and enrolled at the University of Chicago, where he primarily focused on art, music, and literature. After graduating, he worked as a journalist for the Chicago American, then as a music critic for the New York Times. He developed an interest in opera, and in 1907 he went on a sojourn to Europe, taking a leave from his job in New York.

Returning in 1909, he took a new position at the Times as the first modern dance critic in America, an interest that soon enlarged to embrace avant-garde visual art.

Van Vechten was on assignment in Paris in 1913 when he first met Gertrude Stein. She invited him to dinner on May 31, and from that day on, until Stein’s death in 1946, the two of them were steadfast friends. So mutually loyal were they that when she died, she appointed him to serve as her literary executor.

Over the years, they often corresponded, and in 1986, Bruce Kellner edited a two-volume collection of their letters from 1913 to 1946. Among their shared emotions was a qualified affection for the state in which Carl Van Vechten was born. In a 1924 letter to him, Stein wrote: “I have a weakness for Iowa. Iowa is entirely different from the others. It always is . . . I have always felt that about Iowa, even though I did not think of it as having an uplifting effect on American youth.”

In one of her books, a later memoir titled Everybody’s Autobiography, she wrote: “I would like to have seen Iowa. Carl and the painter Cook come from Iowa, you are brilliant and subtle if you come from Iowa and really strange and you live as you live and you are always well taken care of if you come from Iowa.”

The Carl in that passage was of course Carl Van Vechten. And the painter named Cook was another expatriate friend, originally from Independence, Iowa, named William Edwards Cook. Van Vechten was one year older than Cook, and although the two were no doubt aware of each other—and their shared origins—it is unclear if they ever met. Like Van Vechten, Cook also escaped to Chicago, where he studied at the Art Institute. He moved to New York in 1902, and settled in Paris the following year, where he studied with Adolphe-William Bouguereau at the Académie Julian.

Cook’s initial claim to fame took place in Rome in 1907, the year in which Picasso made Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a landmark work in modern art. Cook was invited to become the first American artist to paint a portrait of Pope Pius X. This led to additional portrait requests from the social elite, and in record time, he was condemned to being a dogsbody, when—like Marlon Brando’s character in On the Waterfront—he might have been a contender. Apparently, this was the same year in which Cook met Gertrude Stein, at a soirée at her home.

Alice B. Toklas (whom Stein would later marry) was also there that evening. She made the faux pas of assuming that Georges Braque was an American. But “a real American,” she later wrote, “was William Cook, who had painted the portraits of the English duchesses, and later of the Roman world, including a number of cardinals, but had given this up and betaken himself to etching.”

Carl Van Vechten returned to Cedar Rapids in 1926 to attend his father’s funeral. His brother died the next year, followed by his brother’s wife a year later. With her death, Carl inherited a trust fund worth one million dollars, which supported him and his second wife, Fania, for the remainder of their lives.

William Cook also benefited from an inheritance. His father, a lawyer, owned various farms in Buchanan County, and when he died in 1924, part of his wealth was left to Cook. In 1925, Cook and his wife, Jeanne Moallic, came to the U.S. for six months, a few weeks of which were spent in the town in which he grew up. Shortly after their return to Paris, the Cooks commissioned a little-known architect named Le Corbusier to design for them a “cubic house” in Boulogne-sur-Seine, an architectural treasure known as Villa Cook or Maison Cook.

The last of the three to visit the American Midwest was Stein herself. In 1934, after the publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (which, of course, was Stein’s own autobiography), she agreed to return to her homeland for a seven-month book-promotion tour. She was delighted when she was invited to speak in Iowa City, at the Times Club (on the second floor of what became the Prairie Lights Bookstore). She wrote to Cook that she would “love to speak in Independence” as well, but at the very least perhaps she could see his hometown from the air, if she flew over Iowa during daylight hours.

Alas, it did not happen. On a winter flight from St. Paul to Chicago, where she was scheduled to board a chartered flight to Iowa City, the Midwest was buried by a massive snowstorm, and her plane had to land near Milwaukee. She was taken by train to Chicago, and her Iowa visit was cancelled.

Roy R. Behrens, a writer, designer, and retired professor of graphic design, published a book on William Edwards Cook (Cook Book: Gertrude Stein, William Cook and Le Corbusier) in 2005, and recently produced a 60-minute documentary film on the same subject (Cook: The Man Who Taught Gertrude Stein To Drive) in 2022. See NorthernIowa. Academia.edu/RoyBehrens.Gertrude