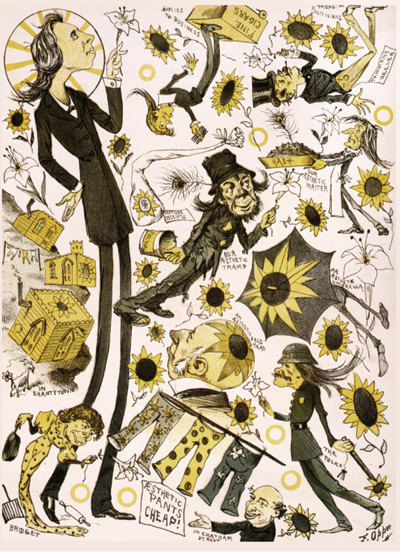

In the final decades of the 19th century, the Aesthetic Movement was regarded by some as offensive. Famously tied to the slogan “Art for Art’s Sake,” it was especially abhorrent to men, who considered it a challenge to the virtues of brazen machismo.

People mercilessly made fun of its male proponents, its aesthetes, including such artists and writers as James A.M. Whistler, Oscar Wilde, Algernon Charles Swinburne (nicknamed Swine-born by critics), and Aubrey Beardsley (known as Awfully Weirdly). They and others were said to promote “unmanly manhood.” They were “preening peacocks,” who by “squandering virility for beauty” were diluting the rough-and-ready identity of men.

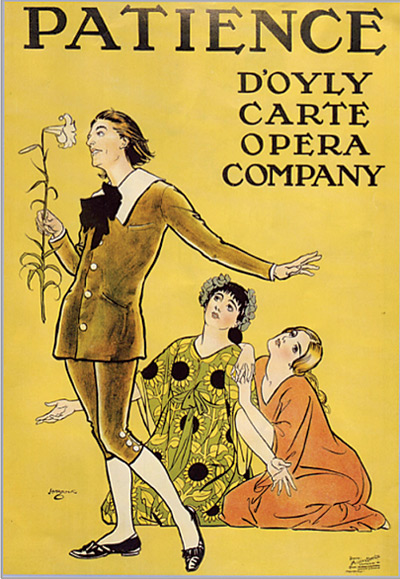

In 1881, the British comic-opera team Gilbert and Sullivan (dramatist W.S. Gilbert and composer Arthur Sullivan) joined the ranks of dissenters who delighted in lampooning aesthetes. They wrote a comic opera (one of their most successful) titled Patience; or, Bunthorne’s Bride. Central to the story are two poetic characters named Reginald Bunthorne and Archibald Grosvenor. Both wore Buster Brown costumes comprised of items matching those of Wilde, Swinborne, and Whistler, including Whistler’s monocle. The production was a resounding success, and continued for 578 performances.

The popularity of Patience in England prompted the idea of taking it on a traveling tour to North America. But for that to succeed, the American public would need to be better acquainted with the Aesthetic Movement, as well as its leading adherents. As a result, Oscar Wilde, who was in need of income, agreed to serve as a de facto publicist who would prepare the way for the opera by touring and talking about Aestheticism in the U.S. and Canada. His tour, which was expected to last four months, began in New York in January of 1882. Sometimes well-received, sometimes not, his stay was extended for nearly a year.

He spent the first six weeks traveling and giving talks about “The English Renaissance” on the East Coast, in New York State, and in parts of New England. Over a period of almost 11 months, he lectured 141 times, the last of which occurred in New York on November 27. Twenty-one of his appearances took place in Canada, while the remaining 120 were given as he toured the rest of the U.S., including the Midwest.

In Iowa, he was featured in programs at Dubuque, Sioux City, Des Moines, Iowa City, Cedar Rapids, and the Quad Cities. When interviewed in Sioux City, he was described by a news reporter as “ladylike.” The article continued: “He occasionally moistened his wrists in a preoccupied way with perfume from a tiny flat vial. His large, liquid eyes rolled upwards at times as he became interested, something as a schoolgirl’s when she speaks to an intimate friend of her latest love affair.” Wilde himself recalled that his Sioux City audience was no less “interested and sympathetic” than others to whom he had spoken, while the newspaper described the audience as “common people, farmers, mechanics, and others of a simple grade of life.”

Cedar Rapids was somewhat less accomodating. In anticipation of Wilde’s arrival, the newspaper asked what the city had done “to be thus afflicted? We thought the scarlet fever was scourge enough for one season. . . . Have your sunflower seeds planted and your statuary well covered with dust.”

Yet, that was far more welcoming than the disingenuous invitation in the Cincinnati Enquirer: “If Mr. Oscar Wilde will leave his lilies and daffodils and come to Cincinnati, we will undertake to show him how to deprive thirty hogs of their intestines in one minute.” Perhaps the most fabled event on his tour was his appearance at the Tabor Opera House in Leadville, Colorado, on April 13, 1882, where he lectured on the subject of “The Decorative Arts.” Leadville was a gnarly mining town, and Wilde had been forewarned that he might be shot if he visited there. It had also been rumored “that an attempt would be made by a number of young men to ridicule him by coming to the lecture in exaggerated aesthetic costumes, with enormous sunflowers and lilies, and to introduce a number of hard characters in the traditional costume of the Western ‘Bad Men.’”

But quite the opposite occurred. The miners lowered him down the shaft to the bottom of the silver mine (perhaps he was on their “bucket list”), where they treated him to a sham banquet, which Wilde recalled as follows: “The first course was whiskey, the second course was whiskey, and the third course was whiskey!” Astonished that a namby-pamby aesthete could imbibe as much as a raucous miner, they invited him to use a ceremonial drill to open a new source of silver, which was then christened “Oscar.” He was given the drill as a keepsake.

So what is all this other stuff about peacocks, sunflowers, and lilies? Reporters often asked just that, because those items had been prominent in Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera. Wilde replied that, as an aesthete, he was fond of sunflowers and lilies because, “of all our flowers in England, [they are] the most perfect models of design.”

As for peacocks, when they unfurl their tail feathers, the pattern of the “eyespots” match the spiral patterns (based on the Fibonacci number series) in sunflowers, pinecones, and the rose-themed stained glass windows in Gothic cathedrals. Given all its mystical qualities, the peacock had long been a common motif in Chinese and Japanese art.

Six years in advance of Wilde’s American tour, Whistler had been commissioned to design a room in the home of a wealthy British art collector, for the purpose of housing his plunder of Asian ceramics. Because Whistler chose to use the peacock as a repeated motif in that project, it is called Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room.

The Peacock Room was purchased in 1904 by the American industrialist Charles Lang Freer. Dismantled, its components were brought to this country, and, in 1919, the room was permanently reconstructed at the Freer Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where it awaits your in-person visit. It is a monument to the Aesthetic Movement, to the genius of Whistler—and Oscar Wilde—and proof of an aesthete’s acumen.

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, designer, and emeritus professor of graphic design. More of his work can be accessed at Northern Iowa.academia.edu/RoyBehrens.