Clemens Gretter was the (unheralded) artist who drew the newspaper cartoons for Robert Ripley’s Believe It or Not. He did lots of other things as well. It might even be said that he left a large footprint during his lifetime. And yet, he is a challenge to track, mostly because when signing his work, he used so many different names.

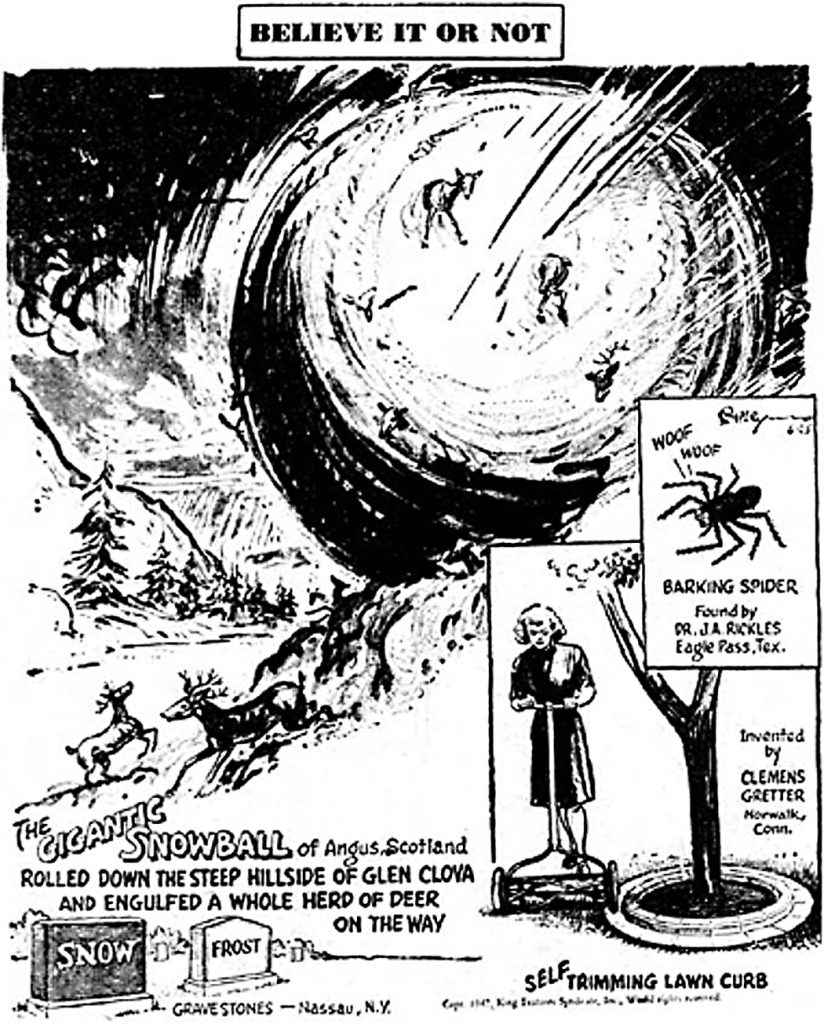

When he was born, he was Joseph Clemens Gretter. As a “ghost artist,” he was not allowed to sign his name to the Believe It or Not cartoons, since Ripley took sole credit for those. But when his other illustrations were published, they were variously credited to J. Clemens Gretter, Clemens J. Gretter, Clemens Gretter, Clem Gretter, Clem Gretta, Clem, and Gretta.

Gretter was an Iowan at heart, but he wasn’t born in Iowa. He was born in Earl Park, Indiana (just south of Chicago, near Lafayette), in 1904, the firstborn of ten offspring of dirt-poor Catholic farmers. His family led a daunting life. When he was a child, they left Indiana and moved to Nampa, Idaho, where Gretter first attended school.

At some point the family moved back to the Midwest and settled on a farm near Crookston, Minnesota. In 1918, when Clem was 14, they traded that property for a farm of equivalent size in south central Iowa, near Avery, which is on the railroad line. It is six miles from the mining community of Albia, and twenty miles west of Ottumwa. The ensuing years were important for him, and in later life he considered himself an Iowan. Some published accounts mistakenly claim that he was born in Iowa.

While still in middle school, Gretter was an altar boy at the Catholic Church in Albia, and admired the parish priest. When that priest was reassigned to Davenport, Gretter expressed interest in going with him, with the intent of studying for the priesthood. His parents objected, and Gretter instead entered high school in Avery.

The day that his parents refused his request was both traumatic and pivotal, as he later described in a strangely confessional memoir about dream interpretation. He recalls that in response to their refusal, he left the house terribly dejected and walked out to a creek on the farm. There he found a familiar deposit of white clay and, sitting down, began to wedge and shape it. He soon became preoccupied, and completely forgot about the disagreement with his parents. Instead, he grew increasingly interested in the process of working with clay. Always responsible for farm chores, he had never been permitted to engage in such useless activities as making clay sculptures. He became all but ecstatic when he found that he was able to make the likeness of a human face (it was a bust of Socrates). It was late afternoon when he gathered up his “artwork,” and ran back to the house to proudly show his parents.

In his memoir, he recalls that as he neared the house, he was met by his mother, who had been frantically searching for him. She said, “Where in the world have you been? We’ve been looking for you all afternoon.” And then, looking down at his sculpture, she said, “And where did you find that?”

“Breathless with excitement,” he recalled in his memoir, “I exclaimed, ‘I made it, mom. I made it!’” He had been “called”—but not to the priesthood. That afternoon, he knew that he was going to be an artist.

Soon after, Gretter entered high school and apparently had a glorious time, since for years he spoke of it glowingly. While attending Avery High School, he wrote, “[I] fell in love with my teacher, and by the time I graduated, every room in the school was decorated with one or more of my statuary.” In his memoir, he published a photograph of her, as well as a postcard she sent him 20 years earlier.

Also in his memoir is a photograph of what is described as “the author’s first sculpture,” a bust of U.S. President Warren G. Harding, with the description that it was “carved by a local farm boy with his cornhusking peg.” It was made of that white Monroe County clay and had never been kiln-fired. When Gretter and his wife returned to visit his Iowa hometown in 1958, he found that all of his sculptures had fallen apart or had been dropped and shattered.

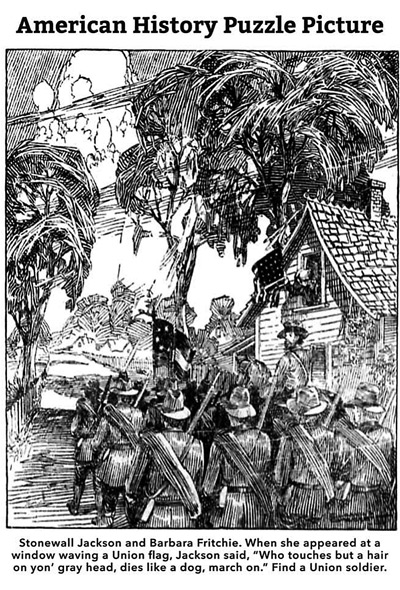

Following his completion of high school, when Gretter’s family lost their farm, they returned to Indiana, where his parents were both originally from. At age 19, he moved to Chicago, where he took art courses at night at the Art Institute of Chicago, while working as a bus boy and clothing salesman during the day. He was subsequently hired by the Chicago Tribune as an illustrator and cartoonist, for which he made hidden-figure cartoons called Hippity Skip Puzzles.

In time, Gretter became adept at drawing and painting, the two skills that enabled him to move to New York City during the Depression and pursue a productive career as a designer and illustrator.

Gretter was prolific. He illustrated magazine stories and provided illustrations for serial novels (such as The Hardy Boys), newspapers, and comic books (including Weird Tales and Fun Comics). As a syndicated newspaper cartoonist, he continued to produce “picture puzzles,” with hidden figures for readers to find.

His claim to fame (of sorts) began in 1941, when he “ghosted” as the artist for the syndicated newspaper feature Ripley’s Believe It or Not, which continued for eight years until Robert Ripley died. Soon after, Gretter and his wife moved to southwestern Connecticut, where they raised four children while he continued to work in Manhattan. He died in 1988.

So far, so good. Or not so good if you read his memoir, Chain of Reasoning (1978), as I did recently. In that book, he claims that in 1964, a system for “deciphering dreams” was revealed to him in a ten-volume set of encyclopedias (published in 1899) that he bought used at a furniture store. It enabled him to unravel arcane encrypted secrets about the universe, none of which I have been able to parse. So compelling were these revelations that Gretter began to send registered letters to Dwight Eisenhower, Pope John XXII, Nikita Khrushchev, and Lyndon Johnson, which are included in his memoir along with their courteous, if cautious, replies.

To confirm his insights, his loyal wife accompanied him on a nonstop cross-continental tour of the Canadian Shield, a large area of exposed rock that forms the ancient crust of the North American continent. And in 1975, in advance of the U.S. Bicentennial, he petitioned his local city council to sanction his proposal to build two “antipodal cairns” (ten-foot pyramids), one in Connecticut (which was actually constructed) and the other on an island near Tasmania, directly opposite on the globe.

That’s all I know—believe it or not.

Note: An internet search for Avery, Iowa, will provide links to online postings about three sandstone and cement pyramid-shaped tombs that are in a cemetery, two miles north of town. They were constructed in 1939 by an eccentric local resident named Axel Peterson, who wanted to be buried in a pyramid. Clemens Gretter, also from Avery, was himself interested in pyramids, but I have yet to find a connection between Gretter and Peterson.

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, graphic designer, and retired university professor. More information can be found at BobolinkBooks. com/Ballast/.