In 1887, 26-year-old Alice Moore resigned as a primary school teacher in Cedar Falls and returned to the region in which she was raised. She accepted a high school teaching post in East Aurora, New York, just outside of Buffalo.

In later years, until her tragic death in 1915, Alice Moore would become known as a writer, suffragette, and feminist. Of particular impact was her collaborative work with her husband, a writer and ersatz philosopher named Elbert Hubbard. Working together in East Aurora, they headed an artists’ community called Roycroft, a project partly inspired by William Morris and the British Arts and Crafts Movement.

Hubbard himself was a Midwesterner, having grown up near Chicago. As a young man, he had been highly successful as a traveling salesman for the Larkin Soap Company. His innovative sales techniques (premiums, product trials, and mail order sales) were widely adopted, and the company thrived.

As it expanded, the Larkin Company moved east to Buffalo. Hubbard acquired a third of the firm, and became the second in command. But as the years passed, he increasingly felt unchallenged and began to imagine a writing career. In 1893, he retired from the company, with a settlement of about two million dollars (in today’s dollars).

His departure was not entirely smooth, even though two of his sisters were married to Larkin executives. He may have played a backstage role in the choice of Frank Lloyd Wright (whom he had known in Chicago) as the architect for the company’s administrative center, the famous Larkin Building.

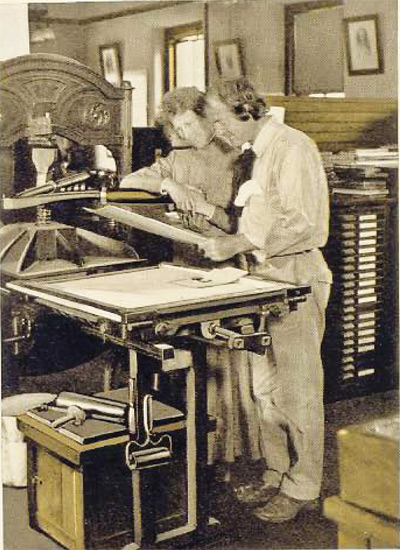

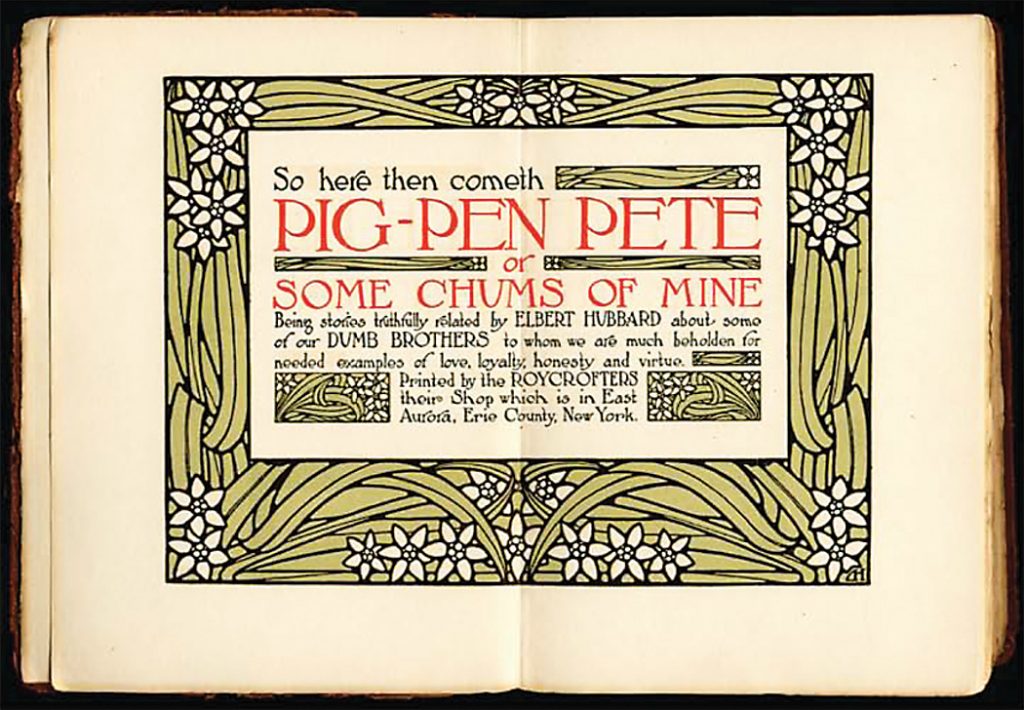

Hubbard’s first wife, Bertha Crawford Hubbard, did not oppose his change of career, and in 1895, they launched a private printing firm, called Roycroft Press (in tribute to Morris’s Kelmscott Press). It was Bertha who designed the title page of their first book, The Song of Songs. That initial endeavor, which resulted in periodicals called The Philistine and The Fra, and a series of biographical essays called Little Journeys, was the first phase in the founding of the Roycroft community.

A phenomenal change of fortune occurred in 1899, when Hubbard published a story in The Philistine about worker initiative and corporate loyalty, titled “A Message to Garcia” (which he claimed he had written in a half hour). When reprinted in book form, millions of copies were sold (possibly as many as 40 million), in part because companies bought them to give out to workers. Elbert Hubbard became a household name and was increasingly in demand as an inspirational speaker.

Hubbard had grown up in Bloomington, Illinois, but he had never crossed the Mississippi until he lectured at Brown’s Opera House in Waterloo, Iowa, on January 15, 1900. His Iowa tour then continued to Cedar Falls, Fort Dodge, Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, and New Hartford. His talks were inevitably well-received, and in October of the same year, he was invited by a friend (Cedar Falls school superintendent O.J. Laylander) to return as the main attraction at the annual meeting of the Northeastern Iowa Teachers’ Association in Clinton.

Two years later, he spoke in November at the opera house in Algona, Iowa, where the tickets sold out in two hours. The following month, an article in the Waterloo Courier revealed that Elbert and Bertha Hubbard had been living separate lives for more than a year. She had filed for divorce (with adultery as the reason) and negotiations about alimony and child support were ongoing (wed in 1881, the Hubbards had raised three sons).

As the story unfolded, it was revealed that Elbert Hubbard had fallen in love with Alice Moore (the Cedar Falls teacher who had moved back to East Aurora in 1887). They had embarked on a drawn-out secret affair, which continued, off and on, sometimes by trysts, more often by impassioned letters. Surely, for everyone involved, the point of no return occurred in the latter half of the 1890s, when Hubbard fathered one daughter (Miriam) by his mistress, then fathered a second (Katherine) by his wife.

The stigma of being an unwed mother would have ruined Alice Moore’s life. She could never again work as a teacher. As a result, the daughter that Alice gave birth to was quietly raised for the first six years by Alice’s sister and husband in Buffalo, and initially grew up unaware that her “visiting aunt” was actually her birth mother. In 1904, when Elbert Hubbard and Alice Moore were finally able to marry, they settled in East Aurora, along with their reclaimed daughter, who was eight years old by then.

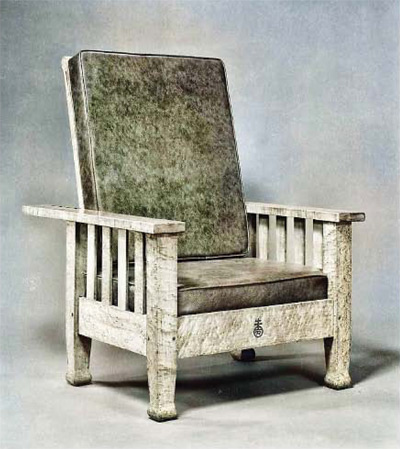

In subsequent years, Alice took over much of the management of the Roycroft community, in part because Elbert continued to tour as a public speaker. The fame of the Roycroft colony grew, thanks to the ubiquity of its publications, but also because its line of products expanded to include not just letterpress printing, but affordable, sturdy Arts and Crafts chairs, lamps, clocks, metalworking, leather craft, and bookbinding. By 1910, the colony had grown to nearly 500 resident workers, with 14 buildings on what was known as the “Roycroft campus.”

As Hubbard continued to travel the country as a “platform speaker,” he returned to Iowa now and then. In 1906, he spoke at the Burtis Opera House in Davenport, at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Bloomfield in 1904, in Waterloo in 1913, and at the Advertising Club in Cedar Rapids in 1914.

At some point, he met and developed a friendship with B.J. Palmer, whose family had established the Palmer School of Chiropractic (PSC) in Davenport. In emulation of Hubbard, Palmer set up his own Palmer Print Shop, made use of marketing techniques that were modeled after Hubbard’s, collected Roycroft books and furniture, and even dressed like “Fra Elbertus,” wearing long hair, a headband, and a flowing Buster Brown cravat (as did Oscar Wilde, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Burley Griffin, and other “aesthetes” of the time).

In 1915, at the height of the popularity of the Roycroft Community, Elbert and Alice tragically died. The United States had not yet entered World War I, and to appeal to all for mutual peace, they boarded the RMS Lusitania at New York to visit England as well as parts of Europe. They were onboard on May 7 when the famous passenger ship was struck by a German torpedo. The Hubbards were among the 1,198 people that perished. They might have survived, but according to witnesses, when last seen, they made no effort to be saved, but instead stood calmly holding hands, resigned to the fate of their drowning.

The Hubbards’ bodies were lost at sea. It is an uncanny addition to note that, five weeks after the Hubbards’ death, the Waterloo Courier published a news article in which a Waterloo resident named George H. Wilson (who until recently had lived and worked at the Roycroft colony) claimed to have Elbert Hubbard’s suitcase, recovered from the ship’s debris. The battered container, the article stated, “is on display in a window on the Fourth Street side of the Black Hawk Building [in Waterloo], and is attracting interested crowds.”

Roy R. Behrens is a writer, graphic designer, and retired university professor. He collects historic design artifacts, including Elbert Hubbard’s books. Examples of Roycroft furniture (purchased from Hubbard by B.J. Palmer), along with correspondence and other items, are housed in the museum of the Palmer School of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa. A major restoration of the Roycroft community buildings in East Aurora NY was completed in 1995, at which time the campus reopened for visiting tourists.

Read more of Roy’s work at ThePoetryOfSight.blogspot.com.