In 1919, Iowa-based writer Woodworth Clum was touring the state as director of the Greater Iowa Association. Given his father’s background as an Indian agent and his own interest in the history between Native Americans and Euro-American immigrants, he drove south from Decorah with the intention of locating a bygone U.S. Army post called Fort Atkinson.

Clum’s father was a newspaper publisher who had been a Western hero of sorts. In the 1870s, as the Indian agent at the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, John P. Clum achieved acclaim when he captured Geronimo without firing a shot. In 1936, Woodworth produced a book about his father’s life, titled Apache Agent. It later became a Hollywood film called Walking the Proud Land (1956), with Audie Murphy playing the role of the elder Clum.

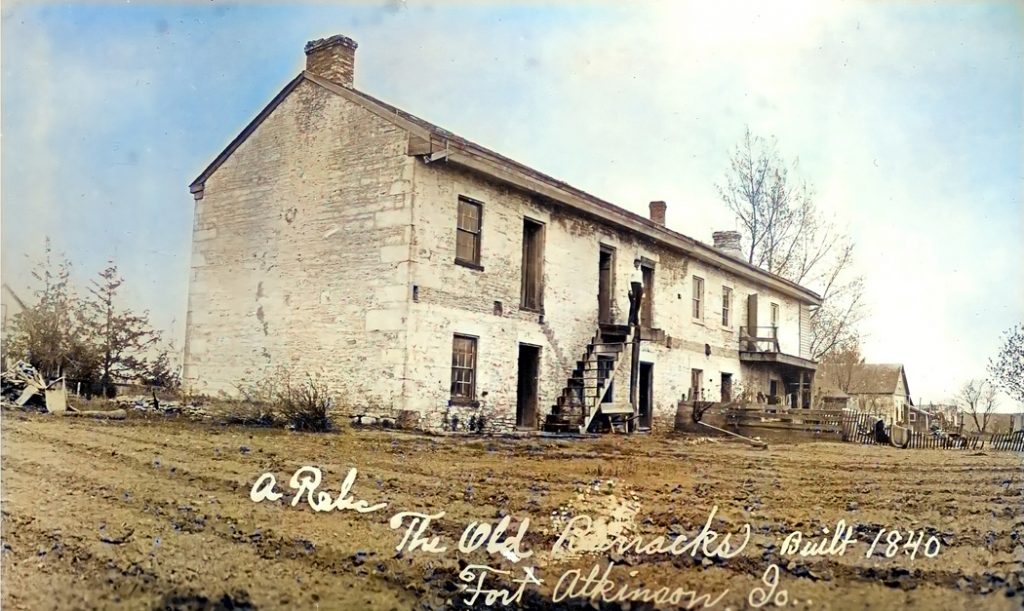

Fort Atkinson must have been easy for Clum to locate, since an adjacent small community had adopted the same name. The historic fort’s buildings, constructed in 1841, consisted of barracks for enlisted men, officers’ quarters, two block houses (with gun and cannon ports), a powder house, a supply warehouse, and a chapel. Made of stone walls two feet thick, these buildings lined the perimeter of a parade ground and were additionally shielded by log stockade walls, from the top of which the soldiers could view the Turkey River, which flows through the scenic valley below.

It is commonly claimed that Fort Atkinson was the only U.S. Army fort that was built for the primary purpose of protecting one Native American group (the Winnebago or Ho-Chunk) from aggressive encroachments by others—including whites—by monitoring a neutral zone. But five years after the fort was built, its soldiers were transferred to fight in the Mexican War. The fort was briefly maintained by Iowa troops, but when the Winnebago were relocated in 1849, it no longer had a purpose. Four years later, the land and its buildings were auctioned off to the public for $3,500.

When Woodworth Clum drove up the hill from the town of Fort Atkinson in search of that historic fort, he was dismayed by what he found. “At the top of the hill,” he remembered, “we turned to the left and came alongside an old stone building, half crumbled away.” This was the remains of the barracks.

Half of the barracks was in ruins, but the remaining half was occupied by what Clum described as “a farmer’s family.” He later wrote, “I asked the wife, as she stood over the washtub in the yard, to tell me where I could find old Fort Atkinson.” She answered that this was all that was left. As he walked the property with his camera, he found that one of the buildings was shelter for the family’s pigs. The place was a literal “pigsty,” he wrote. A cow grazed in the central square. The storehouse was used as a hen house, and chickens were running freely in the ruins of the powder magazine.

Clum was more than just dismayed that day—he was distraught. Weeks later, he published an article in the September issue of Iowa Magazine with the provocative title, “Fort Atkinson, A Pigsty.”

“Oh, Iowa!” his article pleads. “Have material needs gotten the better of us? Have we not gone overboard in sacrificing our history in favor of pork, eggs, milk, and rental fees? Who is the man—or woman—of the hour who will lead a campaign to have old Fort Atkinson restored: to have a good road built to it, and make of it what it should be—a mecca for those who love Iowa, and her history?”

I learned about Woodworth Clum only recently. He died the same year I was born. On the day he toured the ruins of Fort Atkinson, he could not have known that the farmer’s wife was my grandmother, Christina Brandt Behrens. She was my father’s mother, and my father (who was then 18) might have been present that day. Clum took photographs during his visit, and in a view of the barracks, there is a young man at the top of the stairs, who may have been my father, or possibly his brother George. Other children can be seen, not clear enough to recognize, in other photographs by Clum.

When he spoke to the wife of “the farmer” that day, Clum was apparently oblivious of the absence of the farmer. That man in absentia was my grandfather, Diedrich Joseph Behrens. In August of the previous year, while harvesting crops with his neighbors, his shirt sleeve became caught up in a threshing machine, and he had been pulled into it. I cannot describe the death he endured, since I don’t entirely know the facts—but also because it horrifies me to begin to imagine the scene. Help was summoned, but he died within a half hour.

In my brother’s family research files, there is a harrowing photograph of our grandmother as a young widow, a few days after our grandfather’s death. She is standing behind the youngest three of the couple’s seven children. Beside them in the photograph is Aunt Helena, my grandfather’s sister, who had come to console her sister-in-law and help care for the children. Relatives and friends stepped in to offer to adopt the youngest children. But my grandmother insisted on keeping them all, even though repeated crop failures kept them penniless. Unable to stay on the farm they leased, they were soon without a place to live.

Following my grandfather’s death, my grandmother was able to live temporarily in the ruins of the fort, which was privately owned at the time. They lived there until 1920, and they were no doubt the family that was belittled in Woodworth Clum’s appeal to restore an Iowa landmark.

All’s well that ends well. Or so we say. My grandmother and her children (my father, aunts, and uncles) were eventually able to relocate to a more conventional dwelling in the town of Fort Atkinson.

After Clum launched a preservation campaign, the historic fort was purchased by the State of Iowa in 1921. Its formal restoration began in 1958, and it was given the status of a State Preserve. Over the years, extensive restoration occurred. Today, it is once again respectable, and is now the popular site of a festival for reenactments of pioneer life.

Roy R. Behrens is emeritus professor and distinguished scholar at the University of Northern Iowa. For more of his work, see Bobolinkbooks.com. This article is indebted to the work of his brother, Richard H. Behrens, who has extensively researched the history of their family.

Note: All photographs are courtesy of Richard H. Behrens