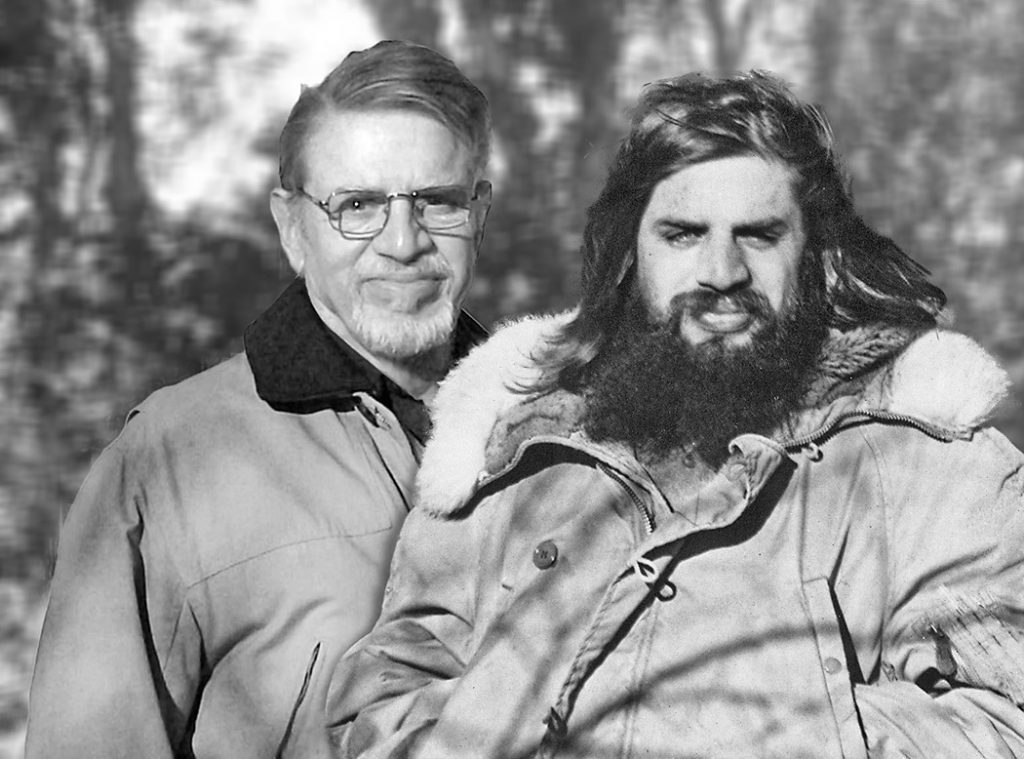

In his new novel Headfirst, indie author Tim Pelton invites readers back to the 1960s as he follows a group of college friends on their (mis)adventures involving sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. The novel is striking for its deep dive into this unique cultural moment, even when the novel struggles to find forward momentum. Pelton, who lives in Fairfield, answered questions via email.

Tell me about the origin of Headfirst. Is the book semi-autobiographical? If not, what led to this collection of characters and their adventures?

Much of Headfirst is a fictionalized version of what happened among a group of friends. In fact, the story is more about what happened among two separate groups of friends as I left one and joined another. Since those days, I have become the unofficial chronicler and storyteller of both. When we’d get together years later, someone might ask, “Hey, Tim, do you remember when those hitchhikers from New York came through?” And I’d be off and running, never letting the facts get in the way of a good story. After an hour or so of were-we-crazy-then-or-what, someone would say, “You should write all these stories down in a book.” But the stories were just stories. They had no spine to give them continuity.

Then one day, one of the old crowd asked me, “What did we do that for? Why did we dress up in funny clothes, let our hair grow out, get high, and mock our parents’ generation?” It was a good question. After a lot of thought, I realized that although I still didn’t know the answer, I had the spine I needed. I began to write, and ten years later, here we are. I’d say what happens in the book is one third the truth, one third the embroidered truth, and one third completely imagined.

Do you plan to write more about these characters?

When I finished the first draft of Headfirst, it was a whopping 145,000 words. I sharpened up my meat cleaver and began hacking away. By the time I had a second draft, it was a much more svelte 113,000 words. But among the trimmings, three sections were demanding a life of their own. So I rewrote each one as a short story and collected them into a slim book called 3 Orphan Stories.

If Headfirst is a decorative tree, then these stories are not budding branches showing new growth, but rather some ornamental cuttings that have been brought in and arranged in a vase. There is still a bucketload of the old stories, but what I’m looking for is a new dramatic through line to hang them on. I do think that Jamie Shipman’s story has been told. Quentin Rickman would probably be the main character of a sequel

Did you always intend to self-publish or did you shop Headfirst around first? What do you like about being an indie author? What do you find most challenging?

My original intention was to follow the traditional publishing path. . . . It didn’t quite work out that way. After being rejected by nearly 30 different agents, I did some serious self-assessment and realized there were three very good reasons I wasn’t making headway, all of them having to do with the fact that the whole traditional publishing system is there to make money. They are not there to discover new voices or to help entertain the masses. They are only there to sell books. And I had three strikes against me before I even stepped up to the plate.

Strike one: I was a debut writer with no name or following. Strike two: Headfirst is too long. . . If a customer is browsing and picks up two books of equal interest but one is thicker, she’ll buy the thin one—80,000 to 100,00 words is the preferred range. Strike three: I had written a book with no genre. If your book doesn’t fit neatly into a well-worn cubbyhole like “cozy mystery,” “urban fantasy,” or “Regency romance,” agents and publicists have no idea what to do with it. And I had written a sort-of historical novel with comic and romantic facets.

It wasn’t so much that I chose self-pub, but that Headfirst chose it for me. Rather than immediately run off to Amazon with my manuscript, I spent a year researching the process—how to build a platform, how to edit it yourself before giving it to an editor, how to publish with little or no money —before I made the plunge.

Do I like it? To continue the metaphor, it’s like jumping into a swiftly moving river for the first time. I’m excited, I’m still afloat, and so far the scenery is fine.

Do you think of yourself as an Iowa writer?

I’m not sure what that is. I have lived in Iowa for a total of about 13 years. Folks I know whose families have lived here for generations probably consider me a tourist. But there is something in the air or drinking water here that inspires a square-shouldered devotion to simplicity, to a confidence that things that were uprooted will grow again. And if someone should notice these qualities in my writing, then I would proudly say, “Yes, I am an Iowa writer.”

Do you have other writing projects on the front burner (or even the back burner)? What should readers expect from you next?

Two projects have been waiting for a long while for me to get to them—The Braided River and The Streeterville War.

The majority of The Braided River was written by my mother, Helen Pelton. In 1981, she began exploring worlds that she had not known even existed before. Starting with the help of professionals, then on her own, she took on the exploration of a multitude of past lives. She found, through almost nightly self-hypnotic regressions, that over the centuries she had reincarnated over and over—sometimes as a man, sometimes a woman, sometimes a hero, a victim, or a villain, but each time with trials to overcome and lessons to learn. For 11 years she made these explorations, keeping detailed notes. Then she wrote the stories of the two most dramatic and interesting lives she had led and collected them into a book. Once it was done, she put the book up on a shelf and never published it.

In 2018, 13 years after my mother had passed away, I took her book down off that shelf. When I remembered how well the stories were told—like little mystery tales—and how the lessons of each life were universally applicable, I took on the task of preparing the work for publication. This meant digitizing, editing, rewriting, updating, and adding a couple of chapters of new material.

One of the most surprising things she discovered is that in nearly every life she recognized the same familiar entities around her that had appeared before but in many different roles. Over the years, this group tried to teach each other the great lessons of life in the only way they are truly learned—in the School of Hard Knocks. The cold-hearted slave owner who works one of his captives to death finds himself in a later life to be a desperately unhappy slave who is raped by her owner. And that owner is, this time, the entity who was once that doomed slave. It is one thing to say, “As you sow, so shall you reap,” but it is quite another to see this law, time after time, playing itself out.

The other project, The Streeterville War, is based on the true story of Cap Streeter. In 1890, Cap ran his old wreck of a boat aground on a sandbar in Lake Michigan a hundred yards from the downtown Chicago beach. He lived on the wrecked boat and began to make a living selling bootleg whiskey that his wife, Ma, made with the still she had built using parts from the boat’s boiler. A year passed and he found that the boat was sitting on an island. The old hulk had changed the currents of the lake, and sand was being deposited like snowdrifts behind a board fence. Cap began to scavenge the city for wagonloads of trash that he could dump into the water. It took nearly eight years, but finally, Cap could walk from his home to Chicago and not get his boots wet. He named the new land Streeterville.

About this time the moneybags and robber barons of Chicago, among them N.K. Fairbank, Potter Palmer, and Marshall Field, decided to remove Cap Streeter from this land, level the ramshackle impromptu settlement of saloons, whorehouses, and shacks, and divide the whole thing up among themselves.

Getting wind of the plot, Cap loaded up his shotgun, dug in his heels, and got ready for the fight of his life.

For several years I have maintained a blog called The Pelton Chronicles, consisting of gently humorous stories about growing up in a small town in Wyoming. Once Headfirst was published, I decided I needed a landing site for all my writing endeavors, so I built the Tim Pelton Author Headquarters (TimPeltonAuthorHQ.com). The Chronicles are all there, as well as Headfirst, and a biweekly newsletter on writing called UpWord. I am also offering a free-for-the-asking digital download of 3 Orphan Stories.