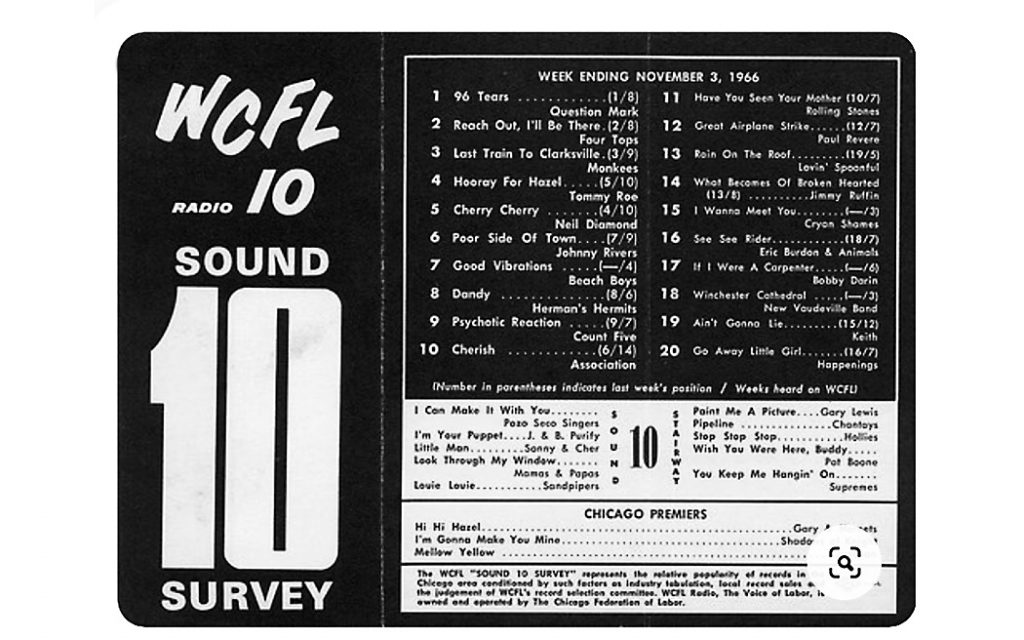

The first music that I ever bought was a 45 rpm record—the 7-inch disc with the big hole. I think it was Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet.” My favorite Chicago deejay, Dick Biondi, would play the latest hits on local AM radio station WCFL, and we’d rush down to the record store to buy the 45 and pick up their latest top 40 list.

As I entered my teens, AM evolved into FM, and I graduated to 12-inch LPs. The 1960s were a wonderful time for long-play records; Dylan started the move toward “concept” albums. No longer was an LP just a collection of unrelated songs. All the best groups created whole stories told in song from start to finish. The move to the LP also gave us higher sound quality than the 45.

When I first got into the audio business, receivers had flashy, oversized FM tuners and phono preamps, as LP records were our prime sources of music. The radio gave us portable music. FM had recently replaced AM radio as the more musical way to listen to broadcast music, which made local FM stations more important as promoters of local music styles. And radios sounded just as good as an LP, as long as the station was strong and close.

Recording a record onto tape was always a good way to avoid wearing out our records. The big reel-to-reel tape decks were the best fidelity choice, but they were a pain to operate. The 8-track tape was already more convenient, but it didn’t have the best reputation for reliability or fidelity.

What looked promising was the new compact cassette, which had recently been upgraded to stereo sound. Advent and Wollensak had just come out with models that were good enough to copy our LPs with decent fidelity, in spite of their skinny tape and insanely slow tape speed. For the sake of casual listening, our records were copied well enough to keep us from wearing out our records. Before long, higher tech companies like Nakamichi came out with cassette decks that were amazing in their ability to come close to LP sound.

Then the boomboxes and car cassette decks showed up. The world of portable music had come of age.

The cassettes that we made from our own record albums sounded sweet, but the convenience of pre-recorded cassettes soon caused great change—their sales soon far surpassed that of vinyl. You no longer had to make your own recording, but there was a big cost—sound quality. Why? For the best sound, they must be recorded in real time. However, that would have made cassettes too expensive for mass production. Instead, they were recorded at super-fast speeds, which made them sound terrible compared to our home recordings or vinyl records.

Convenience kept the cassette selling, however, and it gained momentum with the introduction of Sony’s Walkman and all of the personal portables to follow. Small enough to put into a pocket, with higher fidelity due to decent headphones replacing the cheap speakers, the pre-recorded cassettes sounded BTB (the dreaded “better than before”). Sales surged, leaving the superior sound of the LP in the dust.

Phonograph records had their own cycle of evolution and devolution. The early recordings were pressed onto thick vinyl, and recordings had few tracks to mix—not much for the engineer to mess up. This created full, smooth sound, with simple mic techniques that captured the concert hall beautifully. By the ’70s, record companies had many tracks to mix and they also moved to thinner, cheaper pressings. To fit onto that cheap plastic, they compressed the music, making records with more distortion and less fullness.

Fortunately, pianist and arranger Lincoln Mayorga and recording engineer Doug Sax knew that the old recordings sounded much better. In 1968, they got the idea to skip tape altogether and record straight to the mastering lathe, producing some of the best musical recordings ever made. Direct-to-disc recordings, and the remastered records to follow, gave us new music with incredible fidelity. Some of these recordings are worth hundreds, even thousands today. Perhaps these recordings are the reason why so many continue to be seduced by vinyl.

The recording industry soon saw a new kid on the block: digital recording. It had far less hiss in the background and it had limitless bass—two serious shortcomings of even the best LPs in the world. Using digital tape recording technology, record companies created records off those digital tapes. The grooves were spaced farther apart for the killer bass passages, so the records got much more dynamic. This also made them harder to track. My favorite experience was playing Telarc’s recording of Tchaikovski’s “1812 Overture” recorded with real cannons. Playing it on our best record player, with an expensive tonearm and cartridge, we hardly paid attention to how strident the bells and the strings sounded—we were there for the cannons.

The first cannon made the needle and tonearm jump two inches off the record surface! Then it crashed back onto the record. You can’t imagine how many emotions we felt—hilarity, terror, anger, disappointment, all at once. After a few attempts at adding enough weight to get the needle to stay snugly in the groove, we were happy that we had big Klipsch speakers that could mimic a good cannon shot. We did some loud demos on our most powerful audio systems, but it never compared to the live performance. After all, when the recording was made, that cannon actually blew out some windows 200 feet away!

Paul Squillo is a trumpet player, an audio-video specialist, and CEO of Golden Ears, Inc., in Fairfield, Iowa. He welcomes your feedback at paul@paulsquillo.com.