American novelist Edna Ferber, who was originally from Kalamazoo, Michigan, moved with her family to Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1890, where they lived for seven years. With a population of 14,000, Ottumwa was a rough coal-mining town at the time. Ferber’s Jewish father was a shopkeeper, and she recalled that one evening, she turned a corner and witnessed a lynching. She also remembered anti-Semitic incidents, such as verbal abuse by onlookers as she delivered lunch to her father.

Ferber was undoubtedly acquainted with another Jewish child, a boy of the same age, who also lived in Ottumwa. His name was Carol Mayer Sax. His father, a prosperous downtown merchant named Jacob Sax, had immigrated from Germany. He owned Ottumwa’s finest clothing store, among the largest in the state. Wealthy and civic-minded, Carol’s parents were well-known for their charitable activities. They lived in an opulent residence in what is now known as the Fifth Street Historic District.

After their parents died in the 1920s, Carol Sax and his sister (both of whom had left Iowa years earlier) made an effort to preserve the family’s mansion “as a virtual museum and memorial to their parents, who had filled the home with art treasures, collections of antiques, and rare furnishings.” The garden on its grounds was known as “one of the city’s showplaces.” But in 1945, the property was donated to the church next door, and at some point the house was dismantled.

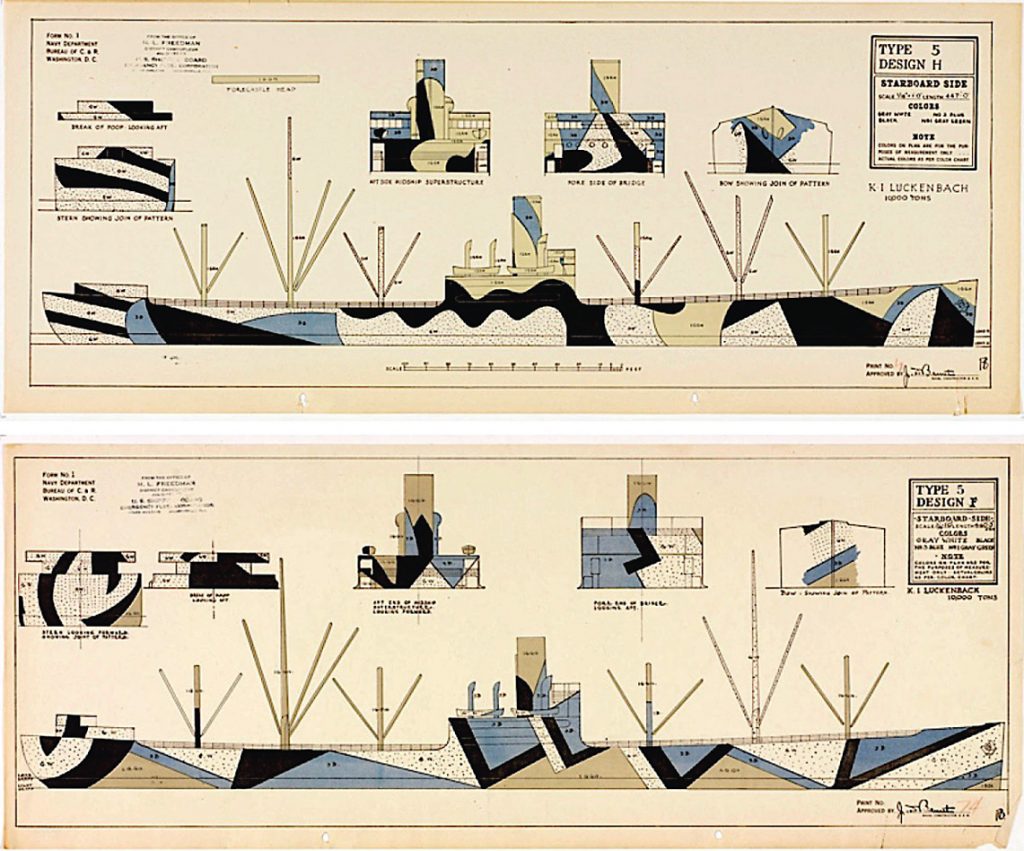

Like Ferber, Carol Sax was destined to have a career in the arts, as a modestly prominent artist and designer in Baltimore and New York (where he designed costumes and theater sets), and as a teacher of art and design at the Maryland Institute of Art and Design and the University of Kentucky. As a cofounder of the Vagabond Theatre in Baltimore, he was an early participant in the Little Theatre Movement (as were Jig Cook and Susan Glaspell from Davenport). And oddly enough, he was briefly notable for his involvement in ship camouflage. During World War I, partly because of his expertise in scenic design (which uses perspective distortions), Sax worked as a camouflage artist (called a “camoufleur”) for the U.S. Shipping Board.

Before all that, he left Ottumwa and enrolled not at a university (where studio art was not yet taught) but at the Art Institute of Chicago. As was customary, he went on to study at the Art Students League of New York and the National Academy of Design. He also attended Columbia University, presumably to learn to teach. If so, he certainly knew and possibly was a student of a Columbia artist-educator named Alon Bement. According to Georgia O’Keeffe, who had also been a student there, Bement was a major influence on her. Like Sax, Bement also served as a wartime camoufleur, applying camouflage schemes to ships.

The war ended in November 1918, and soon after, Carol Sax returned home to visit. He was interviewed in Ottumwa by the Des Moines Register, which featured a story about him on February 2, 1919, with the headline “Iowan Aided U.S. as Camoufleur.” He talked about his civilian wartime duties, which involved developing camouflage patterns for American merchant ships to guard against encounters with German submarines, called U-boats.

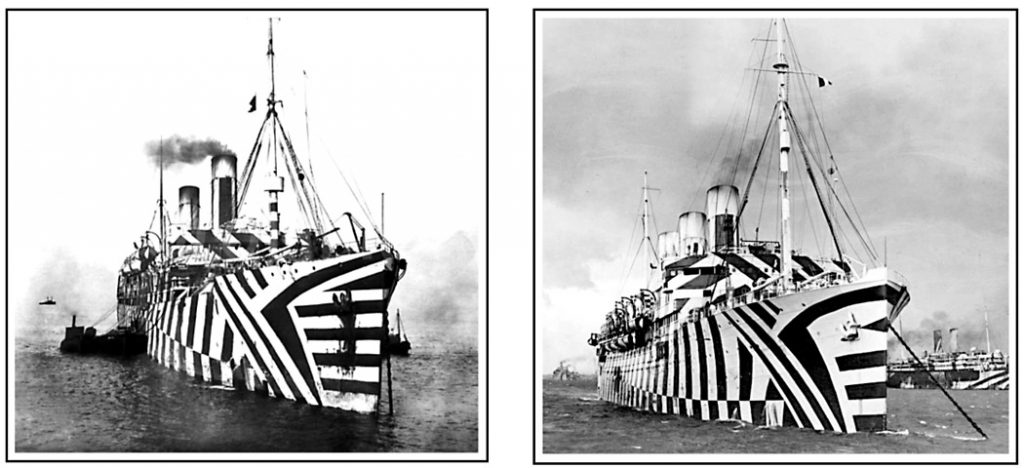

However, these were bewildering camouflage schemes. Unlike ground camouflage, they were not attempts to make a ship invisible, since any vessel was readily detected by the smoke from its stacks as well as the sound of its motors. Instead, this kind of camouflage (known as “dazzle”) was designed to distort the ship’s appearance, as viewed from a distance through a submarine periscope, and to subvert the calculations of the torpedo gunner. In other words, the primary effect of ship camouflage was not to make it hard to see, but to make it hard to hit. Dazzle-camouflaged ships were inevitably lampooned, and described in news stories as “cubist nightmares,” “sea-going Easter eggs,” “a Russian toyshop gone mad,” and even as the delirium tremens.

Following WWI, Sax returned to teaching at the Maryland Institute of Art. But in 1921, he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he served for eight years as Head of the Art Department at the University of Kentucky. There, he founded the Romany Theatre, a “little theatre” that was initially housed inside an abandoned building on the edge of the campus. Its exterior was so dismal that Sax and students came up with a promotional ploy of inviting students, townspeople, and passersby to a “painting party” for the purpose of enlivening the building’s drab appearance. When the party ended, the building was “adorned with gaily colored splotches of paint, campus caricatures, and football scores…” Some people said it reminded them of WWI dazzle ship camouflage, and a magazine described it as “a nightmare, a riot of color, resembling nothing so much as the palette of an artist with delirium tremens.”

Carol Sax left Kentucky in 1929 to work as a theater designer in New York. For the remaining decades of his life, he focused on stage productions and motion pictures, including three brief interludes: one in Paris, in which he tried (unsuccessfully) to acclimate French audiences to American plays; another in Manchester, England, as managing producer of its repertory theater; and in Hollywood, where he was the assistant to film director Alan Crosland (director of The Jazz Singer, the first significant “talkie”). Infrequently, he would return to Ottumwa, to encourage art exhibitions and award scholarships. What may have been his last visit took place in October 1941, when he spoke about “Art and the Theatre” (which turned into a discussion about abstract art) at the community’s art center. Twenty years later, he died in New York at age 76.

Roy R. Behrens is an emeritus professor and distinguished scholar at the University of Northern Iowa. For more information, see BobolinkBooks.com/Ballast.