Franc Johnson Newcomb (née Frances Johnson) was born in 1887 near Tomah, Wisconsin. Her father was an architect, while her mother taught in an area school that included Native American children. Orphaned before she reached her teens, Frances later adopted the professional name of Franc, in tribute to her father. In research publications, she is nearly always cited as Franc Johnson Newcomb.

After high school, Franc remained in Wisconsin, and taught Menominee children for several years at Keshena. In 1912, partly for health reasons, she moved to the Southwest, where she taught Navajo children at a government boarding school at Fort Defiance, Arizona. In one of her books, she remembers the reluctance of the Native American students when she tried to teach them English. The breakthrough came when she asked them to teach her Navajo, a process during which they themselves learned English.

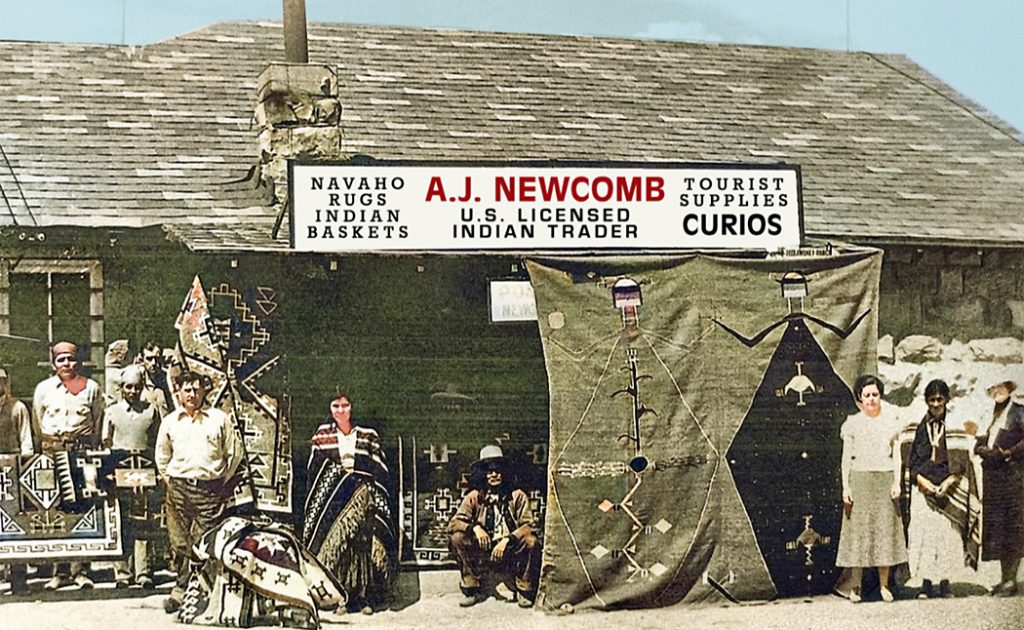

At Fort Defiance, Franc met a young trader named Arthur J. (called A.J.) Newcomb, who was from Manchester, Iowa. They married in 1914, and went on to operate a trading post on the Navajo Reservation in a remote, isolated region of New Mexico halfway between Gallup and Farmington, now known as Newcomb. Their marriage continued for 32 years, during which they raised two daughters.

A.J. had purchased part of the trading post in 1913 and moved there to learn the business. One of the first Navajos to befriend him was Hosteen Klah, a prominent chanter, medicine man, and weaver. When Franc arrived the following year as A.J.’s wife, she too became a close and long-term friend of Klah, and 50 years later, she wrote a book about his life. While respectful of the rituals and traditions of the Navajo, she also helped them cope with the diseases introduced by Whites. Often traveling to remote hogans to provide modern medicines, she became known as Atsay-Ashon or Medicine Woman.

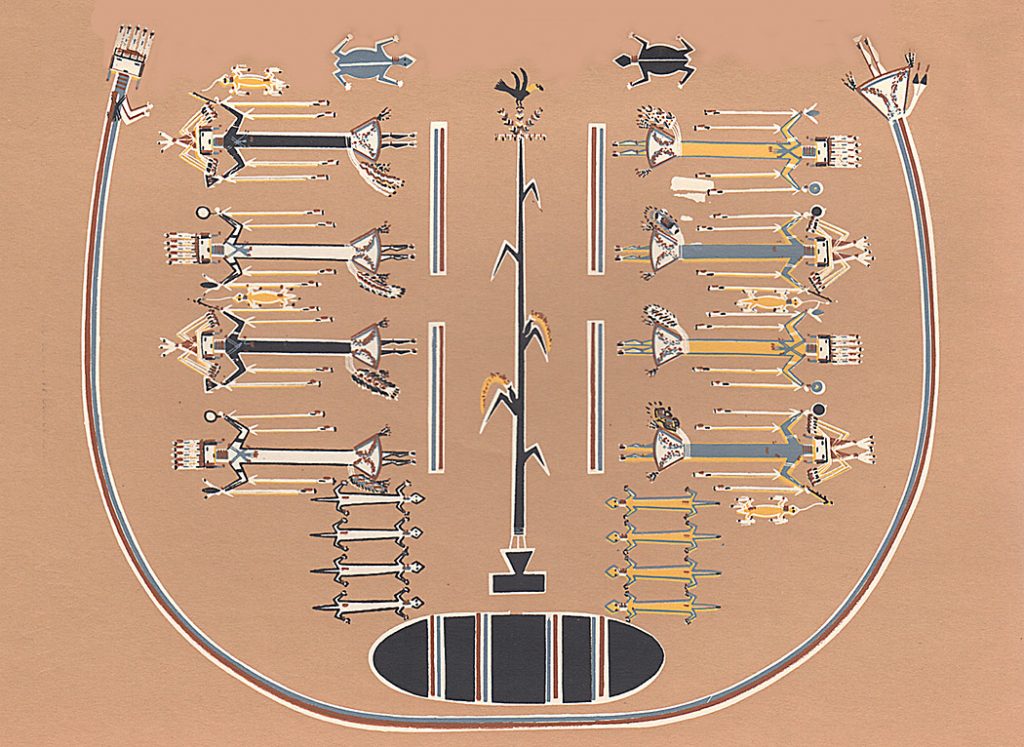

Having gradually earned the trust of Klah and others, Franc was allowed to observe rituals that non-Indians had been strictly excluded from. These included sandpainting ceremonies in which complex, colored patterns were painstakingly rendered in sand, then promptly destroyed at the end of the ceremony.

At first, as a silent observer, she memorized features of the sandpaintings, then made drawings afterwards. “Since pencil, paper, or camera were not allowed in the lodge, I had only my memory to depend on,” she later wrote. “. . . In later years I trained myself to concentrate, and if allowed to remain in a ceremonial hogan for a half-hour, I could reproduce the painting without an error.”

With Klah’s and others’ approval, she gained increasing access and was eventually permitted to record about 500 sandpaintings, which she recreated in paint on board. Some Navajos opposed this, condemning it as sacrilege, but Klah consented cautiously. Forty-four of these were reproduced in her first book, Sandpaintings of the Navajo Shooting Chant (1937), while other paintings by her were preserved and are now exhibited at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe.

Although she replicated scores of Navajo sandpaintings, Franc did not regard herself as an “artist” in the usual sense. She was a writer and amateur ethno-anthropologist for whom paintings were a reliable means of preserving the sandpainting tradition.

She did this in other ways as well. For example, Hosteen Klah had been a weaver of Navajo rugs since the late 1880s. She asked if he might consider weaving monumental rugs (as large as 12-foot square) that would replicate ceremonial sandpaintings. While reluctant at first, he eventually agreed, providing that they would be displayed respectfully as wall tapestries, not as rugs to be walked on.

Klah’s first such tapestry was purchased by the wife of King Gillette, who had made a fortune from his invention of a razor with disposable blades, the iconic Gillette razor.

Klah’s second tapestry was purchased by a wealthy heiress named Mary Cabot Wheelwright of Boston, who would establish the Wheelwright Museum in 1937. By the time of his death in that same year, Klah had woven 25 large tapestries, based on ceremonial sandpaintings.

A few years later, Franc Johnson Newcomb published a book on Navajo Omens & Taboos (1940), and later co-authored A Study of Navajo Symbolism (1956). In 1964, when she authored a biography of Hosteen Klah, she dedicated it to the memory of her former husband, Arthur John Newcomb, who had died in 1948. They had divorced two years earlier.

A decade prior to their divorce, A.J. was living at the trading post, while Franc was in Albuquerque, where their daughters were attending school. A news article described the devastating fire that destroyed their Newcomb compound (their home, the trading post, the manager’s house, the camp cottages, and the garage) and most of their finest possessions. Insurance made it possible to rebuild part of the post, but the psychological damage was irreparable. According to one biographical source, “When fire destroyed their trading post in 1936, her husband’s alcoholism became acute, straining [Franc] Newcomb to the breaking point.” She moved permanently to Albuquerque, where she established a day-care center for children and a visiting nursing service.

At the same time, she was an active participant in the founding of the Wheelwright Museum (where much of her sandpainting research is housed). Funded by Mary Cabot Wheelwright, with Klah’s consent, the hogan-like museum was designed by well-known Southwest painter, designer, and architect William Penhallow Henderson, who had designed murals for Frank Lloyd Wright for the Midway Gardens in Chicago.

Of Franc Johnson Newcomb’s books, perhaps the finest is Navajo Neighbors, published in 1966, when she was nearly 80 years old. This fascinating memoir, as Helen M. Bannon has noted, is “nonfiction prose blending history, autobiography, and folklore.” While some have dismissed Franc’s research as amateur, Bannon concludes that others (such as Native American author N. Scott Momady) have “applauded her realistic portrayals of Navajo life. To Newcomb, Navajos were people, not objects for study. This basic assumption permeates Newcomb’s works, enhancing their value as a record of the personal dimension of intercultural communication.”

Roy R. Behrens is emeritus professor and distinguished scholar at the University of Northern Iowa. His grandmother was Claire Pentony Stewart from Manchester, and two of her sisters, Madge and Isabel Pentony, married A. J. Newcomb’s brothers, who were also traders in New Mexico and lived among the Navajo in the vicinity of Gallup.