It’s somewhat of a cliché to say that a certain artist is the best musician you’ve never heard. But it is clear that Darrin Bradbury is an original and imaginative performer most Iowans have not yet had the privilege of hearing. That’s why I decided to interview him during this Covid-19 crisis. Bradbury deserves the exposure, and Iowans would benefit from knowing about the man and his music.

In the past, critics have dubbed Bradbury the new John Prine because of their shared empathy and humor in writing about ordinary events and people. Indeed, both mix the commonplace with the absurd to show the deeper meanings of everyday events, such as eating breakfast or watching squirrels at play. When I asked Bradbury if he could take the late Prine’s place, he bristled.

“John Prine was amazing and one of a kind,” he said from his Nashville residence. “No one is an heir to his throne. Think of Prine as sort of a songwriting Johnny Appleseed planting seeds that bloomed.” Bradbury noted that Prine was a big influence and also inspired many other musicians.

“The most valuable thing Prine taught us was to write in our own voices in a language that anyone from any socioeconomic class could understand,” Bradbury continued. “That requires hard work.” He compared learning from Prine’s music to taking out a car engine and rebuilding it for yourself.

For Bradbury, Prine also demonstrated the importance of brevity. “He could say in 3 minutes what would take Bob Dylan 16.”

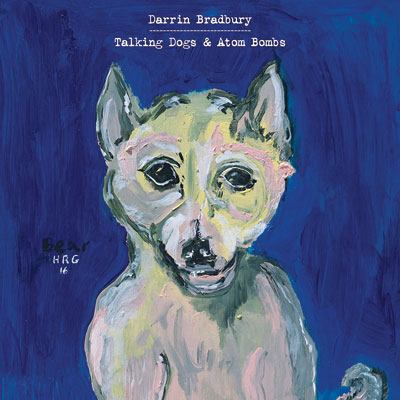

The 11 songs from Bradbury’s latest album, Talking Dogs & Atom Bombs, are short. The longest one is less than three and a half minutes and the quickest just over one minute in length. “I don’t like to push a song. When it’s over, it’s over,” Bradbury said glibly. The tracks concern, as one song title put it, “The American Life.” The lyrics to this piece present our common experiences—French fries, the 4th of July fireworks, and heading to the mall. But then it gets deeper:

The American life is franchised fear and cow milk

The American life is the presumption that people are dumb

The American life is fried chicken taking a political stance

It’s a church built like a stadium

Bradbury’s observations move from the superficial to the profound without making a judgment. The implications are left for the listener to decipher. He doesn’t feel the need to explain, but the lyrics are strongly resonant.

Bradbury just released a video of the last song on the album, “Dallas 1963,” in which he dreamt he was Lee Harvey Oswald and had just assassinated President John F. Kennedy. The song ends up with him wondering what the dream meant. Bradbury’s too young to remember the actual event.

“That was an actual dream,” Bradbury said. “After talking with my girlfriend about it, I realized it was a way for me to talk about 9/11 without mentioning 9/11.” He was in high school in New Jersey, about six miles from the center of Manhattan, when the planes hit the buildings. “I was putting on my gym shorts when I saw it happen on the small black and white TV above the lockers. It had a profound impact on me.” Bradbury explained that he had always been obsessed with the Kennedys (John and Bobby) and the promise of America they stood for. The two things fused in his mind, because they represented the death of one America and the birth of a new one.

“Things got better after 9/11. The nation came together and healed,” Bradbury said. He presumes the same will be true after the Covid-19 epidemic. Bradbury knows these are dark times, but he believes that the American people will do more than just get through these troubled days. They will prevail. “It’s the ebb and flow of history. The new normal might not be the same as the old one, but we will work through it,” he said. Bradbury admits to being a fervent patriot and nostalgically mines the nation’s past as a way of shedding light on the present.

Besides JFK, Bradbury’s songs also mention people like Lenny Bruce and Jack Kerouac as iconic American symbols, even though they were dead before he and most of his listeners were born. “It would seem disingenuous for me to write about hopping trains or working with coal miners to make a point. I see these people as modern American mythic figures like Paul Bunyon that can be used to set the stage for my musings.” His songs are populated by actual people and places, presented with a twist.

For the past six years, Bradbury has been living in Nashville. He moved from the Garden State because he couldn’t find places to work with like-minded musicians. Bradbury said he was not intimated by all the talent he found in Music City—instead, he was motivated.

“I didn’t feel threatened by it,” he said. “I saw Nashville as the Ellis Island of songwriting: the place where if you try your best and work hard, you will succeed. The music business is not a pyramid with a few people on the top and most people on the bottom. Instead, it is like a choir. Everybody has a place. You sing your note to the best of your ability, and we all win.”

He mentioned that nobody stays in the spotlight forever and being famous has never been his goal.

“I know it may sound corny, but I believe in the sovereignty of art. My job as a songwriter is to tell truths.” He quickly added, “In these times, we know who is important—the doctors, nurses, and those that put their lives on the line for the rest of us. Music helps us get through the dark days, but we always need to remember its place in the larger scheme of things.”