Near the end of every July since 2014—the first summer I taught in Beijing—I have had to say goodbye to Master Lu. It’s always hard. I never know for sure if I will ever see him and my other tai chi friends again, not just because Master Lu is in his 90s, but because my university contract is from year to year, my 30-day working visa reissued each summer. Although I have an official Certificate of Merit declaring me an “International Summer School Honorable Teacher,” I never know for certain that I’ll be back next July.

What would I miss if I could not return to my tai chi friends? Here’s the short list: 1) the exhilaration of moving in concert with a group of people on the other side of the planet who call me their friend; 2) ongoing corrections of my tai chi posture and form; 3) many impromptu language lessons.

Posture corrections and language lessons often coincide. After the morning exercises, Liang Hua lifts my arms away from my sides. She pushes her toe against my shoe to position my feet. “Song, song,” she says, with a long oh. Others join in, dropping their shoulders and letting their arms droop.

“Sooohng,” I say with them, and add, “Relax.”

“Relaaaax,” they repeat. We all go limp together.

If I do this—Chen Jinfen shows me on another morning, bending her knees and throwing her shoulders back—instead of this—now she softens the angle of her knees, rounding her shoulders—the result will be “Tong!” She grimaces and points to her knees. “Tong!”

I get it. Pain! If I bend my knees incorrectly, I will feel pain. Luckily, I already know how to say, “I don’t want.” It’s a necessary survival phrase, especially while shopping. “Bu yao!” I say, with feeling. “Bu yao tong!”

Someone asks if I am a teacher. I say in Chinese, “Yes, I am a teacher.” Someone else asks if my husband is a teacher, too. I have no idea how to say “laboratory coordinator” or “musician” or, for that matter, “retired,” so I say “Wo airen shi airen.” My husband is the husband. All the women laugh pretty hard.

Smartphone translation apps are useful—one saved us from ordering a bowl of small intestines one time in Japan—but they are no substitute for looking a person in the eye while speaking from your heart, your brain, to theirs. This past July, when I found that Sun Ruxin, whom I first met in 2014, had cut her long hair into a chin-length style, I delighted both of us by saying, “Wo xihuan ni de tou fa!” I like your hair!

In 2018, my relationship with my tai chi friends took a great leap forward. My wonderful teaching assistant Tao Huiling agreed to serve as translator and help me interview them. Here’s some of what we learned one Sunday morning:

Sun Ruxin, the graceful one with the new haircut, told us her interest in tai chi began five years ago; she saw Master Lu in the park and simply joined him one day. Chen Jinfen turned to tai chi after mountain climbing, swimming, and dancing, all of which were a great burden to her knees, she said. No wonder she warned me of “tong.” Liu Renrong, a former accountant now retired, has been playing for four years (in Chinese, you play tai chi) to keep fit. Sixty-four-year-old Yang Guilan began when she was 23. She credits tai chi with allowing her to manage diabetes without medication. Liang Hua, who works at the campus hotel, told us that her father was a great proponent of tai chi and acupuncture.

Their stories reminded me of the reason my friend Sarah Lamb and I took up tai chi in Iowa City back in 1997. Sarah had been diagnosed with ALS and hoped tai chi would help her stay active longer. Perhaps it did.

Liu You, the young man who hits trees, told us he works in an optometry shop and does ba chi for health and fitness. He wore a t-shirt that said:

Dream what you want to dream.

Go where you want to go.

Be what you want to be.

That afternoon, Tao Huiling and I met Master Lu in the Park of Family Names. Master Lu brought the red leather-covered notebook I had given him as a good-bye gift and asked me to sign the first page. He gave us some things he had written, a two-page autobiography and a list of “luckinesses” numbered one through ten. Among them: his career as an engineer and his “happy and harmonious family.”

The night before we left Beijing, Tao Huiling emailed me. Master Lu had called to ask her what time we were leaving. He was coming to the hotel to see us off!

In the morning, I come down the hallway from the elevators, rolling my two suitcases into the hotel lobby in front of me, and there he is, standing at the marble counter of the front desk, writing a note on hotel stationery. He’s got a button-front shirt over his white t-shirt and the white baseball cap on his head. He doesn’t look up as I come around the end of the counter. I have to say, “Master Lu!” before he turns and reaches for my hand with the same little exclamation of discovery and welcome he gives me every morning when I show up in the park.

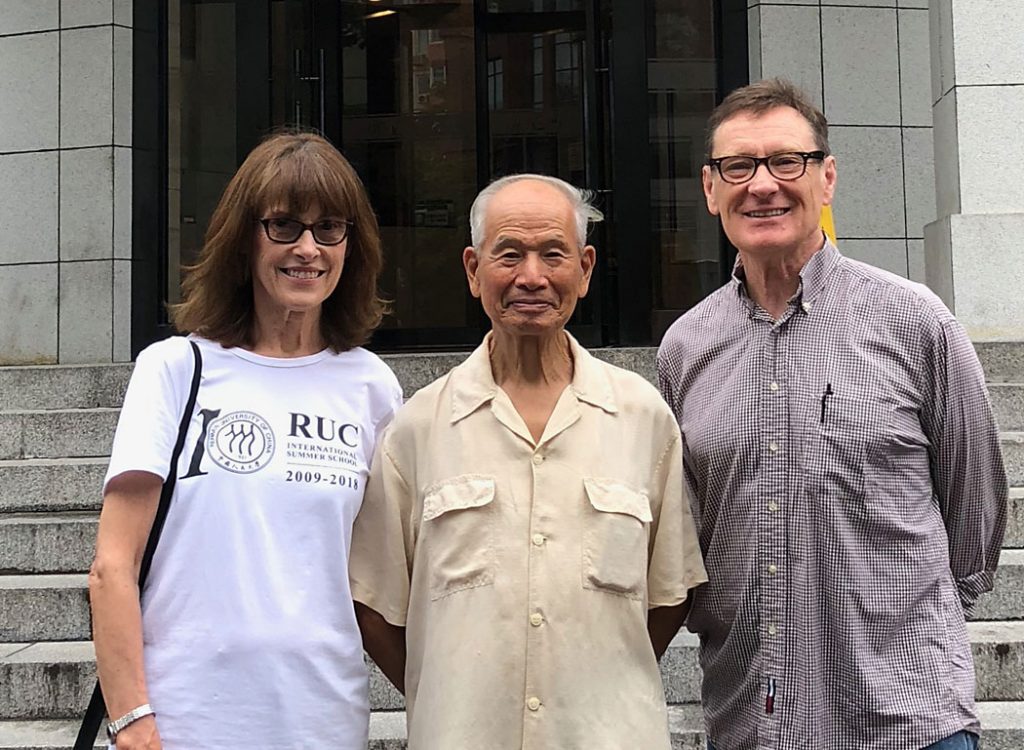

Master Lu carries two of our suitcases down the steps to the street, brushing off the young man in uniform outside the door who tries to help the old guy with the suitcases. The friendly hotel concierge takes several photos of my husband John, Master Lu, and me. Then Master Lu helps us roll our suitcases out to the waiting taxi.

Now we are in the taxi and he is on the sidewalk, smiling and waving. John thinks Master Lu is looking a little misty around the eyes. I’m too misty myself to tell.

Read Part I here: Tai Chi in Beijing. with Friends

Mary Helen Stefaniak is the award-winning author of The Cailiffs of Baghdad, Georgia. She teaches fiction writing in the MFA program at Pacific University and in the International Summer School at Renmin University in Beijing.