I feel guilty. For years I highlighted wonderful new offerings online, such as a new website for buying books (Amazon, at a time when it only sold books); a great new auction site (eBay, before it got swamped with goods direct from China); and an incredible new search engine (Google, at a time when AltaVista was the most popular search engine).

It was fun introducing you to these wonders, and readers were deeply appreciative.

But now you know about all the great online resources, and the wonder has devolved to the point where I tend to write about grave new dangers. I feel guilty for introducing you to these things. But you gotta be aware of them.

This month’s grave danger is “deep fake” videos. There’s now free software available online that anyone can use to create fake videos. This capability created a big stir in April of last year when a one-minute video of former president Obama calling President Trump a profane name went viral. The video was clearly Obama, and the voice clearly his, but the words he was saying were something he didn’t actually say.

You can watch it here.

It was done via artificial intelligence on a powerful computer using free software called FakeApp. It took skill and 56 hours of processing time to accomplish this, but the technology is only going to become more accessible. Many such software tools are being developed, and some professionals even envision a day when such videos can replace actors in movies.

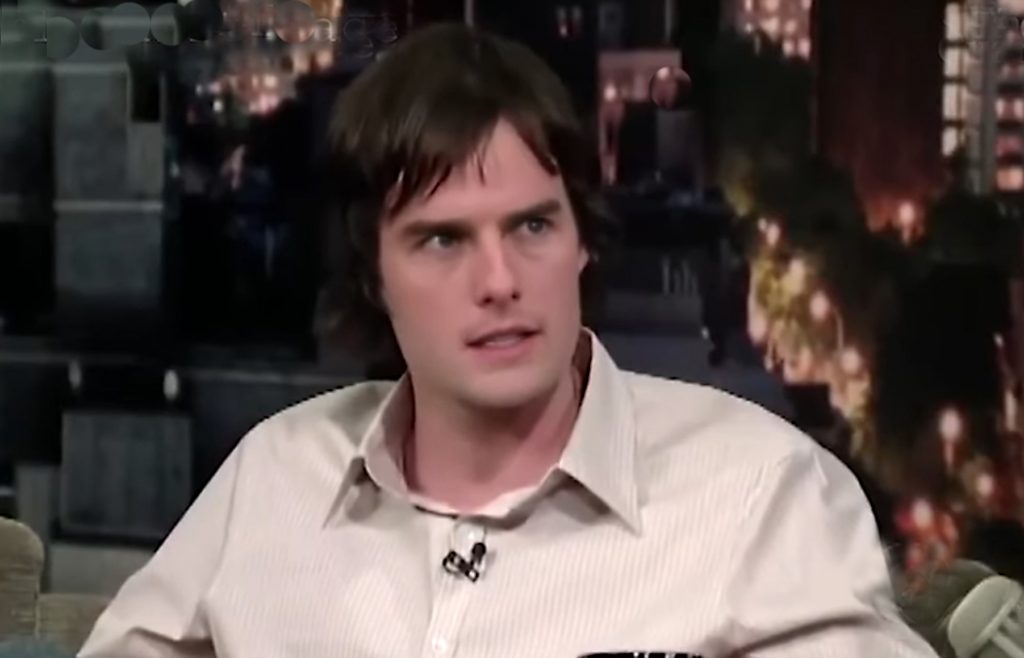

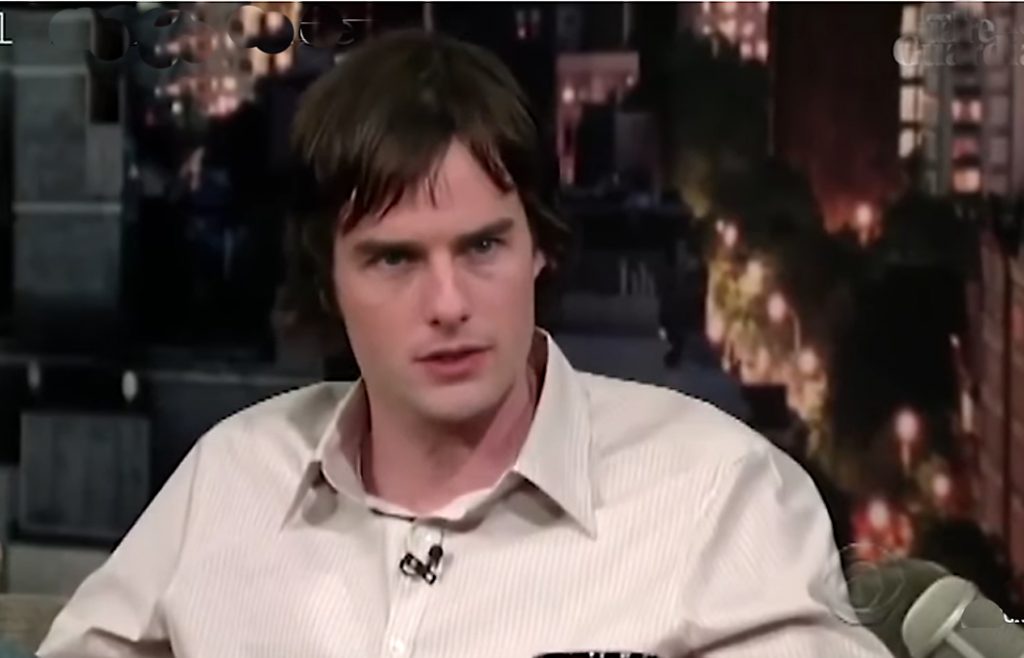

Many more examples online go beyond this early, somewhat rudimentary creation. You can find some entertaining ones in this article by The Guardian. It includes a video of comedian Bill Hader being interviewed by David Letterman. During the interview Hader does an impression of Tom Cruise, and as he does so, his face changes to that of Cruise.

There’s also a video of martial artist Bruce Lee replacing Keanu Reeves in a four-minute segment from The Matrix, along with several other examples.

The point of the article, and of the person in the Czech Republic who has released 20 of these videos, is that you can no longer believe what you see online. The gates are opening, and you can expect to see a flood of deep fake videos that, unlike these demo examples, are intended to deceive.

Millions of people were deceived by videos of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that went viral in May, purporting to show her being drunk or babbling incoherently. In fact, an analysis of one of the manipulated videos showed that it was slowed to 75 percent and her voice manipulated to conceal the fact that the video wasn’t playing at the normal speed. Another manipulated video made her speech sound slurred. Both President Trump and his personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, linked to these videos on Twitter.

It was easy to verify that the videos were manipulated because the original videos, in which Pelosi was completely normal, were available online.

The bottom line: you are going to be encountering deep-fake videos, with some meant to entertain—but many meant to influence your perspective.

And this will create an additional problem. Suppose a politician does indeed make a controversial, bigoted statement and gets a lot of criticism. In the era of deep fakes, the person will be able to claim, “I didn’t say that. It’s a fake video.”

Expect a lot more of fake everything. Software programs that use artificial intelligence to generate natural language are sometimes referred to as chatbots. These are being used extensively to influence opinion, with an estimated 20 percent of the political posts on Twitter during the 2016 presidential election being the work of chatbots. In addition, chatbots are estimated to be the source of 60 percent of posts on Twitter that discuss “the caravan” of Central American migrants.

On Instagram you’ll find fake influencers. For two years, Lil Miquela was very popular on that website, building up 1.6 million followers, who assumed she was a real person. Instead, she was a “virtual influencer” created digitally by a Los Angeles company, which last year finally revealed that she was computer generated. There are many more like her.

If you want to see something really creepy, look at the photos on the website This Person Does Not Exist (https://thispersondoesnotexist.com). The realistic photo that appears is computer generated, and each time you refresh your browser, it creates a new one.

The web was born with a vision of democratizing information—removing the barriers to publication and access, and making information available to all. It has done that. But it has also created a situation where we need to be wary of everything we see.

Okay, now an admission: I’m fake. Just kidding!

Find column archives at JimKarpen.com.