Two fabulists—both in translation for English readers—offer captivating novels arising from expansive imaginations and filled with enigmatic events. Whether the organizing year is 1962 or 1984, each book offers contemporary readers an immersive experience.

CoDex 1962, by Sjón

It’s reasonably easy to describe the structure of CoDex 1962, which is the overarching title given to a collection of three linked novels written by the Icelandic author Sjón and translated by Victoria Cribb.

The first book, Thine Eyes Did See My Substance, is a story of love blossoming in the face of extreme danger. The second, Iceland’s Thousand Years, is a story of murder and mayhem in service of mysterious goals. And the third, I’m a Sleeping Door, is a science-fiction story set in contemporary times blending the mythic aspects of the earlier entries with modern-day science.

But this synopsis is woefully inadequate. CoDex 1962 is a book of wonders. From its narrator—a person fashioned of clay in book one, brought to life in book two, and examining his existence in book three—to its narrative structure—a whirligig of genre, tone, style, magic, science, and more—CoDex 1962 is startlingly inventive and original. It is filled with allusions, but it is never derivative. It explores conventional forms, but merrily and simultaneously undermines those forms. It is concerned with serious issues and ideas, but it is never weighed down by overt seriousness.

Each zig and zag of the trilogy is surefooted, and that is perhaps Sjón’s greatest accomplishment in CoDex 1962. The reader consistently and wholly trusts the narrator (and by extension, the author) no matter how outlandish the story becomes or how circuitous the route from beginning to end turns out to be. This is a book to be both devoured and savored.

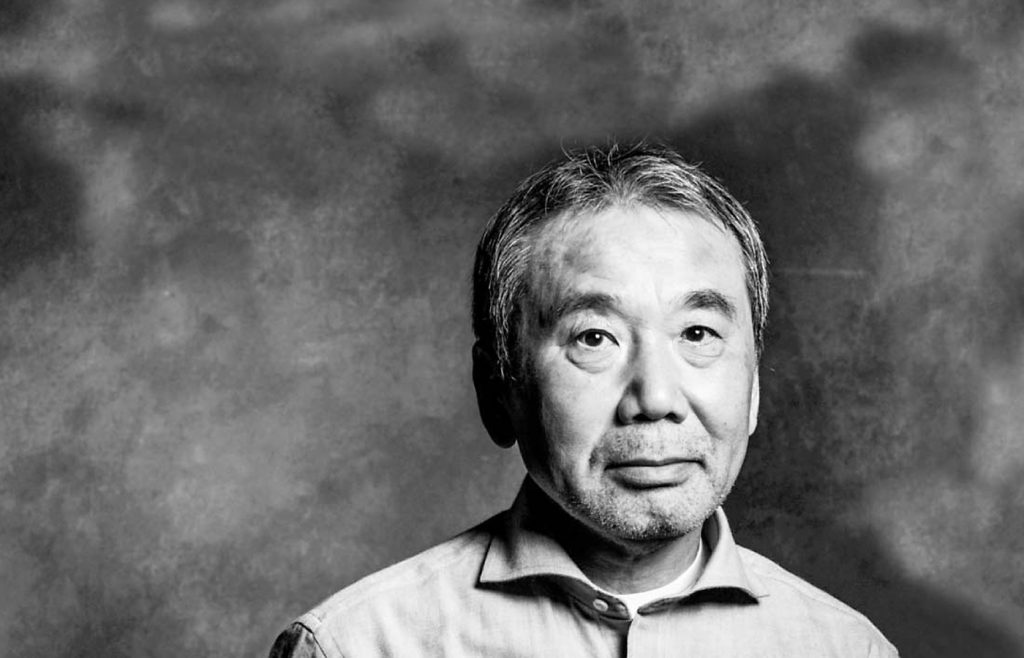

1Q84, by Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, first published in English in 2011, is also a three-volume work. The first two portions of the novel were translated into English from Japanese by Jay Rubin; Philip Gabriel translated the third section. The title is an allusion to George Orwell’s 1984, taking advantage of the fact that “q” and “9” are homophones in Japanese.

Over its more than 900 pages, 1Q84 relates the story of Aomame, an adept killer of men who commits domestic violence, and Tengo Kawana, a writer who finds himself employed to secretly improve a novel by a teenager so that it might be worthy of a major award. Both characters, who knew one another as children, are mysteriously transported to an alternate version of 1984 and embroiled in a battle with a religious organization and the supernatural beings at its heart.

While Murakami is often thought of in connection to Kafka—in part because of his themes, but also because he has won the Kafka Prize and the Czech author is the namesake of a protagonist in Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore—I found that 1Q84 put me in mind of the work of Philip K. Dick. Readers of Dick’s alternate history masterwork, The Man in the High Castle (or indeed any of Dick’s many explorations of undermined realities), will find much to enjoy in 1Q84.

That said, Murakami seems, to this reader at least, to have a firmer hand on the tiller of his novel; part of what makes Dick’s prose so captivating is the sense that the whole framework could fall apart at any moment. Murakami’s novel imagines a tentatively stable reality, but the author seems sure of its foundation throughout.