A brief, magical time comes each spring when serviceberry, dogwood, hawthorne, apple, plum, cherry, and pear fill our yard with sweet, white blossoms. So it was a shock last year when a friend shared an article stating that, with the exception of wild plums, “All the other white flowering trees in today’s environment are an ecological nightmare, getting worse and worse every year and obliterating our wonderful native trees from the rural landscape.”

The article, “The Curse of the Bradford Pear,” by Durant Ashmore of Greenville News, is an excellent example of the mindset behind the war on invasive species. Like most wars, this one is long on exaggerated threats and short on accurate understanding of the perceived enemy. The Bradford pear, for example, hardly qualifies as an “ecological nightmare” compared to, say, mountaintop removal or clear cutting. About 20 years ago, a local spa planted an allée of these ornamental trees along their entrance drive. If these Bradfords have any intention of taking over the surrounding landscape, they are cleverly biding their time.

Of course, many species of plants, animals, and insects do threaten to take over a new environment. Like the Bradford pear, these so-called “invasives” are often introduced to their new homes intentionally. Kudzu, a.k.a. “the vine that ate the South,” was cultivated as recently as 1953. That’s the year the Department of Agriculture removed kudzu from its list of recommended cover crops. In 1970 it officially became a “weed” and in 1997 a “noxious weed.” All along, kudzu was simply being an opportunist.

When a species like kudzu explodes in the environment, it is easy to see it as an invader and seek weapons to combat it. However, the herbicides, pesticides, and bulldozers that are used to fight “invasives” rarely achieve lasting victory and always create collateral damage. A better approach is to copy the “invasive” plant and become opportunists ourselves. In her book Beyond the War on Invasive Species, Tao Orion describes in detail a kudzu economy where “kudzu provides abundant yields of both human and animal food, fiber, medicine, compost, small business opportunities, and land restoration activities.”

Even without the changes that humans introduce, nature is never static. To work with nature we must become equally flexible. This brings up perhaps the most controversial front in the war on invasives—the restored prairie. Tallgrass prairie was once the dominant ecosystem of Iowa. But before that we were a conifer forest. Before that, a lake. Somehow the tallgrass prairie won out as the state’s unofficial nostalgic ecosystem. Certain plants are designated as “prairie” and all others “invasive,” bringing to mind the current debate on who in this “nation of immigrants” is an immigrant.

Prairie restorations involve seeding and often reseeding desired plants, plus constant weeding of the bad guys. There are, however, two huge changes that have occurred since the tallgrass prairie disappeared: the loss of large, free-roaming buffalo herds and the indigenous humans who had managed the prairie for generations.

Trying to maintain any static state is fighting nature, whether that ecosystem is a prairie, a soybean field, or a lawn. So-called invasives are often playing a role in nature’s own program of restoration. This is the case with tree of heaven, which was immortalized in the book A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Tao Orion points out that this invincible tree could grow in the concrete of New York City because “it thrives in poor, acidic, and salty soils.” Furthermore, this tree, which most gardeners despise, “has been used to revegetate mine tailings and tolerates high levels of atmospheric pollution.” It is simply responding to conditions that humans have created. The same can be said of teasel, which grows well in the depleted fields of Iowa and helps to restore our soil.

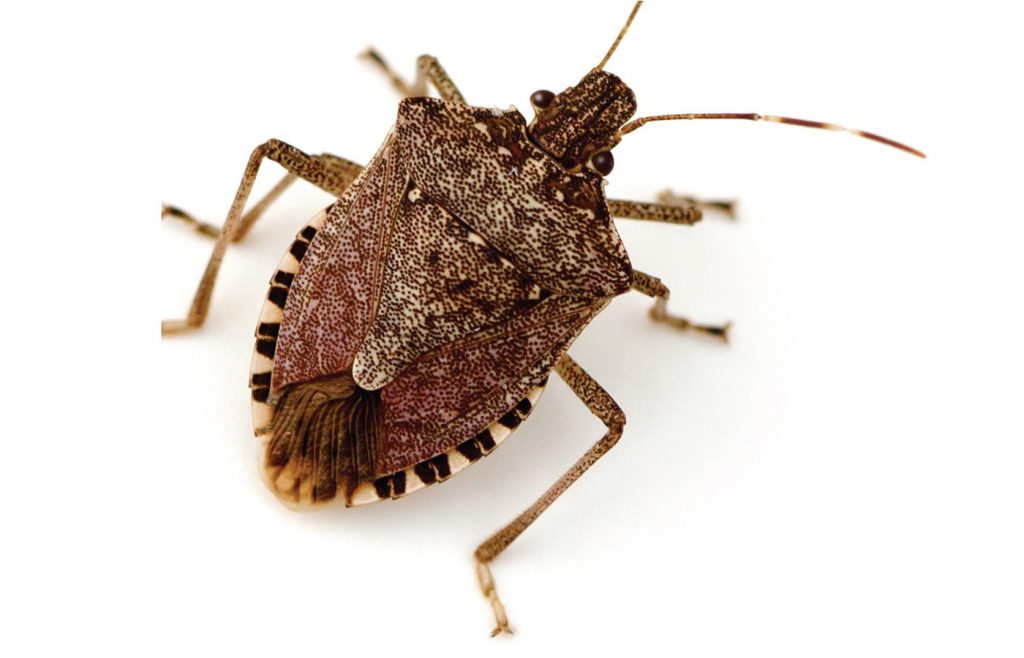

Nature’s addiction to growth and change is the ultimate solution to “invasive species.” Last month The New Yorker published a thorough report on the fast-spreading brown marmorated stinkbug, and it is a classic tale of free trade and opportunism. This particular variety of stinkbug has existed since forever in East Asia. It was kept in check by another opportunist, the samurai wasp, which laid its eggs in the eggs of the stinkbug. The wasp eggs hatched first and had their meal right at hand. Sometime in the last 50 years, this stinkbug made its way across the sea, probably as a stowaway in a shipping container. Like so many immigrants before it, the bug found freedom from persecution on the East Coast of North America and began to move west. If you haven’t found it yet in your crops or curtains, you will.

The article points out that there is no happy ending to this tale because there is no ending at all. Fortunately, there is a positive trend. What goes up must come down, and that includes the local population of stinkbugs. Places that first experienced the stinkbug explosion are now seeing a sharp decline. This may seem like a small consolation when your dog squishes one on the carpet and releases the smell that gives this bug its name.

To hasten the decline of the stinkbug population, entomologists are breeding samurai wasps and hoping they can live up to their name. While no one can predict the impact of these wasps (they don’t sting), theyseem like our best shot at working with nature and not against it. If you know any productive uses for stinkbugs, the world is waiting.