On Thanksgiving Day my family, like many families across the nation, gathers around the dining room table with empty bellies and full hearts. We take a moment to say grace and thanks, and then we turn eager eyes to the crowning masterpiece of our Thanksgiving feast: Grandma’s macaroni and cheese.

This ooey-gooey marvel of melted chunks of Cheddar swimming in elbow macaroni and Velveeta-spiked white sauce has been on our holiday table for as long as I can remember. I never questioned the tradition until I got married and my husband started attending family Thanksgivings. He took in the bubbling hot, cheesy goodness sitting in its place of honor and declared, “More proof your family is weird.”

That got me to thinking. Why am I eating macaroni and cheese for Thanksgiving?

My first thought was that maybe macaroni is an Iowa thing. My husband is from out of state, and Thanksgiving menus vary from state to state when it comes to side dishes. In New England, for example, you’ll find creamed onions and a very historic dish called Indian (cornmeal) pudding on the table. And you’ll find oysters in the stuffing. In the South, the stuffing is cornbread, while in Minnesota the stuffing is wild rice. Bread stuffing is the Iowa favorite, along with green bean casserole and apple Snickers salad. In the Mid-Atlantic they actually serve sauerkraut for Thanksgiving, and in the West and Southwest feasters enjoy Frog Eye Salad, the ingredients of which include pineapple, maraschino cherries, marshmallows, mandarin oranges, egg, and orzo—now that’s weird!

But, as it turns out, while macaroni and cheese is a standard addition to the Southern table, it is not common to the Midwestern spread. Thanksgiving macaroni is apparently not an Iowa thing.

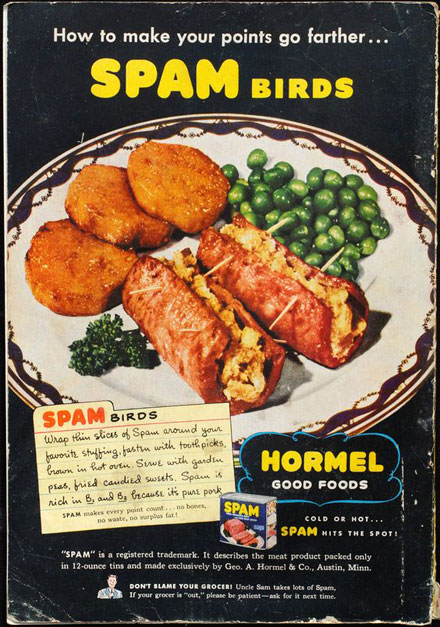

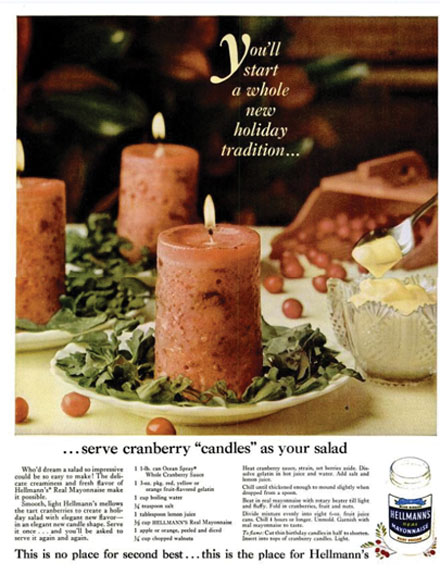

I got to thinking, however, that maybe it was a Velveeta thing. Food manufacturers have long been trying to integrate their particular brands into holiday traditions. A 1944 Hormel ad, for example, proposes you try Spam Birds: “Wrap thin slices of Spam around your favorite stuffing, fasten with toothpicks, brown in hot oven.” In a 1960 ad, Hellman’s mayonnaise suggests starting a whole new tradition by serving cranberry salad “candles.” And in case you’re thirsty, a 1967 ad from Dr Pepper supplies this gem: “Just heat Dr Pepper or Diet Dr Pepper in a saucepan until steaming hot. Then pour over a thin slice of lemon.”

Even nonfood companies have embraced the Thanksgiving spirit. A ’60s-era cigarette ad suggests following Thanksgiving dinner with “the peaceful feeling that comes from good digestion and smoking Camels.” Meanwhile a 1975 aluminum foil cookbook reveals a photograph (with recipe) of an unidentifiable cream-colored gelatinous square dubbed “Frozen Jellied Turkey-Vegetable Salad.”

A quick search of vintage Velveeta marketing, however, did not turn up any Thanksgiving ads featuring macaroni and cheese. Apparently Velveeta advertising had little to do with the macaroni on my family’s table.

So, I hypothesized, maybe I have history to thank for the macaroni. I don’t mean history in the sense of the Pilgrims and Wampanoag in 1621. But I thought the dish may have snuck in somewhere along the evolution of Thanksgiving tradition. So I looked into it.

Guess what! Few of the dishes we enjoy today can be traced back to the Plymouth feast. From the two surviving written accounts (one by Plymouth Governor William Bradford), we know for sure that the first Thanksgiving featured waterfowl, venison, corn, and turkey. Using archeological remains and going by descriptions of early 1600s gardens, we can guess that squash, beans, fish, chestnuts, and onions were also on the table. The Colonists didn’t have butter or wheat flour, which means there was no bread, stuffing, or any kind of pie, including pumpkin pie. The Colonists also had no mashed potatoes or sweet potatoes, since in 1621 potatoes had yet to reach North America. And there probably wasn’t any cranberry sauce, since the Colonists had very little sugar.

If the Pilgrims weren’t eating stuffing, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, pumpkin pie, or cranberry sauce, then how did these dishes make it into our traditional Thanksgiving meals?

The answer rests with Sarah Josepha Hale, a Victorian writer and the person largely responsible for creating Thanksgiving as we know it. In addition to being a prolific writer, Hale was a longtime editor of the popular magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book. In 1846, she began publishing editorials and petitioning U.S. presidents, governors, and senators to establish Thanksgiving as an annual national holiday. Throughout her campaign, which lasted 17 years, she published Thanksgiving recipes and menus. By 1863, when Hale finally persuaded Lincoln to establish a national Thanksgiving holiday (as a way to help unify a country split by Civil War), American cooks were well-armed with the recipes for a “traditional” Thanksgiving meal.

A recipe for macaroni and cheese does appear in an 1861 Godey’s Lady’s Book, and period writings mention macaroni and cheese as a dish on the Victorian-era Thanksgiving table. Aha! Maybe I was finally on to something!

I called my mother to see if I had hit upon the truth. Her explanation, however, was simpler than I expected: “Grandma always used to make macaroni and cheese for family dinners because little kids love macaroni and cheese. The grandkids and then the great-grandkids came, and the macaroni became the staple to have at every family gathering because it’s something that everybody loves.”

Of course! On a holiday of thanks and celebration with loved ones, it makes perfect sense that Grandma first placed macaroni on the Thanksgiving table to make her family a little happier.

Grandma Nyswonger’s Macaroni

Cook 1 box macaroni and place in 9″ by 13″ pan. Cook white sauce: 1 stick butter, 6 Tbsp. flour, and 3 c. milk. Add 3″ chunk Velveeta. Pour over macaroni and add salt and pepper. Cut up a package of Cheddar or Colby Jack cheese and place chunks randomly in macaroni. Bake at 350° until cheese melts, about 30–45 minutes.

Jocelyn and Tim Engman are the proprietors of Pickle Creek Herbs in Fairfield.