A lifetime of “why nots” has led Chuck Mitchell down a variety of paths and created a man with a remarkable reservoir of knowledge and an endless supply of stories he’s quick to share.

His is a positive, adventurous attitude. For Chuck, most every situation presents wonderful possibilities—whether he’s drafted into the army, meets an intriguing woman, or discovers a deteriorating gem of a building.

Born in New York City, Chuck grew up in farm country north of Detroit. A rather sickly child, his free time was spent exploring the woods and cultivating a strong love of nature that he maintains to this day. The Mitchell family had a fondness for musical comedies—he wistfully recalls as a boy seeing Finian’s Rainbow and Carousel at theaters in a vibrant downtown Detroit. Singing became a part of his life.

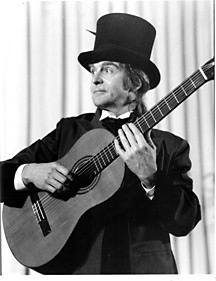

At Principia College, on the Mississippi River bluffs just north of St. Louis, Chuck majored in English and drama. When he graduated, like so many others he headed off to New York to make it big in theater. He got a job (and a room) at the Henry Street Settlement House, went to auditions, and took guitar lessons. “When I left college, there was no one to play while I sang, so I had to learn to play something. A guitar was more portable than a piano.”

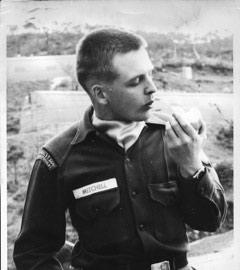

Four lessons later, having almost mastered “The Streets of Laredo,” Chuck was drafted. Guitar in hand, he went off to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he learned to drive a tank and use an assortment of weapons. Then he spent a peaceful year in Korea as a reporter for Stars & Stripes and as a hoofer in musical comedy reviews, entertaining the troops.

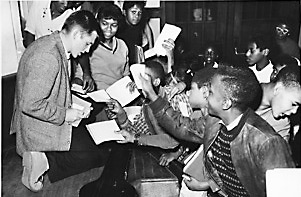

Chuck returned to Detroit and became staff writer for the Great Cities project, a public school experiment bankrolled by the Ford Foundation to develop programs for educating “culturally deprived” children. A program called Head Start was one.

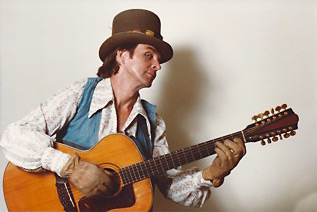

The folk music scene in Detroit was taking off, and nights found him singing in saloons and coffeehouses. By 1965, he was performing at Detroit clubs like the Chessmate and The Retort, bumping shoulders with the likes of Mama Cass, Jose Feliciano, Tom Rush, Gordon Lightfoot, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Odetta, and Buffy St. Marie. He quit his day job and focused on music.

In Toronto, on his first out of town gig, Chuck met Canadian songwriter Joni Anderson from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. He found work for her on his circuit of Michigan clubs, and Joni made the magic journey (it was by train, actually) to the U.S. folk scene.

After a whirlwind romance and little more than 36 hours spent together, Chuck said, “Why not?” and proposed. Joni said yes. So Chuck and Joni Mitchell played the folk club circuit and gin rummy until they divorced in 1968. Some time later, Joni ended up at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, and Chuck ended up in Keokuk.

As the nation’s taste in music changed and the folk clubs closed, Chuck moved on to house concerts and residencies (as a singer and guest lecturer) at various colleges around the country, one being Western Illinois University in Macomb. After his third visit to WIU, when it came time to head home to Greeley, Chuck decided to trade the tedium of Interstate 80 for the leisurely byways of the Heartland. Why not?

So it was that on a golden afternoon in September 1979, Chuck found himself headed west on US 136, waiting in line at the Hamilton-Keokuk bridge while a barge locked through on its way downriver. Curious about the houses he saw clustered along the Keokuk bluffs, Chuck rumbled across the old metal bridge and took the first right up the hill to the foot of Concert Street. Concert Street appealed to the musician in him, so he turned left, climbed another block, and came upon a tall brick house with a “for sale” sign in its yard.

He jotted down the realtor’s phone number. Had he backtracked and headed out of town on Main Street, that probably would have been the end of his Keokuk adventure. Instead, he zigzagged his way along the bluff to Grand Avenue, around Rand Park, then on up River Road. By the time he’d reached Montrose, he was thoroughly intrigued by what he’d seen.

And it hit, again. Why not? He didn’t know a soul, but he felt drawn to this place. Why not buy a tall brick house overlooking the Mississippi. He’d never owned a house before. Three visits and three months later, he did.

With Keokuk his new base, Chuck continued to travel and perform. He made several appearances on Prairie Home Companion, including one when he arrived in St. Paul by speedboat from La Crosse, Wisconsin, after three nights camping along the Mississippi River, and took a taxi from the marina to the theater just in time for the show. “Garrison really liked that,” Chuck says.

Chuck’s stage credits include Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man (twice), Woody Guthrie in Woody Guthrie’s American Song, Carl Sandburg, Bertolt Brecht, and repertory theater in the U.S. and the U.K. He’s also sung countless public school concerts and shows for seniors at meal sites and nursing homes around the country.

In Keokuk, he’s sung for Grand Theatre fundraisers, for bus tours and school kids, and the 2000 Gore/Lieberman Presidential Campaign when Al and Joe came through town.

For the 1990 edition of “Rollin’ On The River,” Keokuk’s annual blues fest, Keokuk Junction Railroad brought up the beautifully restored Chief Keokuck Club Car from St. Louis. Jim Wells, ROTR’s show organizer, invited Chuck to team up with Keokuk native David Marion to do a club car show of Mark Twain stories and Stephen Foster songs. On the spot, the two concocted the first rough and ready version of what became Mr. Foster & Mr. Twain. Their club car audience loved it. And it grew into a full-length performance of Stories and Songs in The Great American Tradition. Chuck and David have performed their homemade show in theaters across the Midwest for the last twenty years.

A few years ago, with the help of owners Terry and Karen Sparrow, Chuck tried to start a weekend folk club at the 4th Street Café. It didn’t work. “You need a critical mass of folks who like folk music,” Chuck says “Keokuk doesn’t quite have it.”

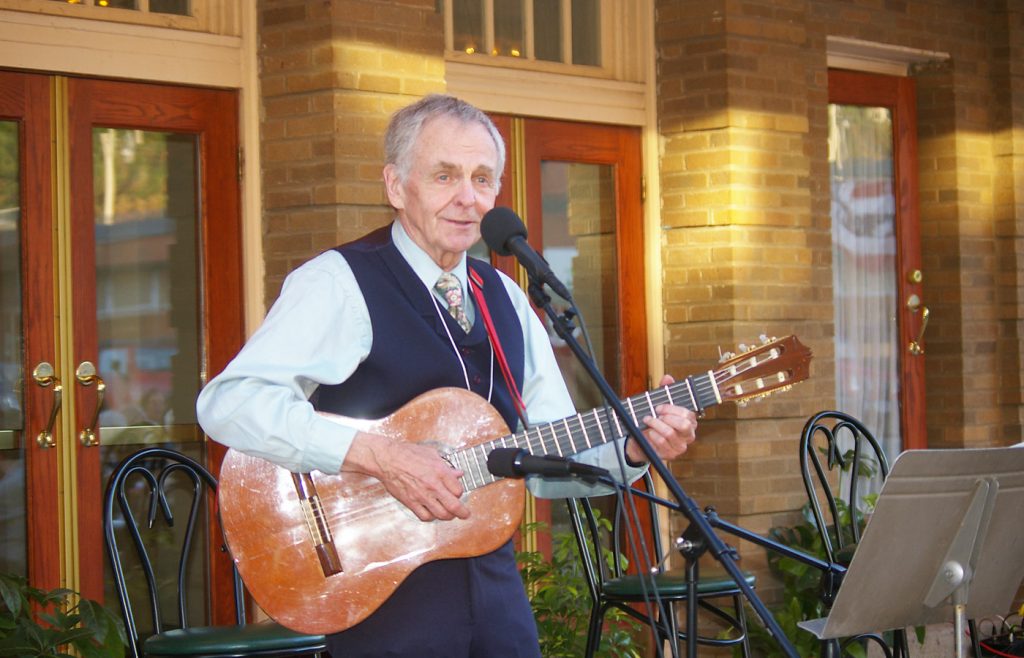

Recently, Chuck has found a home away from home at Cafe Paradiso in Fairfield, where he often performs. He is working hard at his music, practicing more and writing new songs. “I love what I’m doing now, it’s different somehow, and I want to keep working on it.” And why not? His recent shows have gotten great reviews.

Chuck’s wife of many years lives in Wisconsin, by a lake at the end of a long driveway, where their two children were born and raised. “They’re country kids, like me,” Chuck says, “but their mom got them started making music early, when they were five, with itty-bitty violins.” Now accomplished young adults, their daughter doubled in English and music and is a concert violist, and their son (“he reads scores like I read emails”) is finishing a degree in math and “composing music for alt rappers. That’s what I call it. He calls it ‘making beats.’ ”

As for his other connections to Keokuk, they are deep, and some have been difficult. Many of the old buildings that drew him here are no longer standing—the Friendly House and the Old Middle School, for example—in spite of his and other’s intense efforts to save them.

Chuck has put his own blood, sweat, and money into some places. In 1996, after 16 happy years of travel, and music, and work on his own brick house “built foursquare on the compass in 1879 by steamboat captain Abraham Martin Hutchenson,” Chuck found out that another brick house he’d always fancied, just down the street from his place, was about to be torn down.

That bothered him. The house had an extraordinary history. It had begun as a modest two-story built in 1850 by wholesale grocer John Cleghorn. Then in 1852 Cleghorn engaged William Harrison Folsom, a Mormon engineer, to make his little house into a big house. Folsom had worked on the Erie Canal before coming to Nauvoo, Illinois, and his crew jacked the Cleghorn house up off its foundation with several dozen screw jacks and timber cribbing, raising it a foot or so a day, and gradually laid a new first story under the original two to make a three-story house. They also attached two (three-story and two-story) additions to the rear of the elevated original structure. Folsom’s ingenious engineering had created a frontier mansion.

Chuck believed that demolishing the Cleghorn house would erase a unique and irreplaceable piece of Keokuk. Could he save it?

Why not? He bought the Cleghorn house, hired mason John West and carpenter Dan Dawkins and a lot of others and they gutted, steam-cleaned, and restored the structure, photo-documenting every structural clue of its peculiar past in the process. “So we know it’s not a local legend, it actually happened,” Chuck says.

“Time will tell, but I think I’m done with hands-on historic preservation. It’s so expensive and time-consuming. I’ve gotta move on.”

And move on he has. He’s thinking about what he wants to leave behind. Given all the years he’s been a singer, Chuck has few albums to his credit. His first priority now is to record “my own stuff” and get it online and CD. He plans to collaborate with his son. “Will wants to work with me on my songs, which is terrific. He has a gift for making music.”

Meanwhile, Chuck plays his guitar, and eats his greens, and works out, and swims laps. “I wouldn’t be around today if it weren’t for the Keokuk YMCA,” he says. He fully expects to be ready to say “Why not?” another time or two.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of the Confluence, Keokuk’s Cultural and Entertainment District’s quarterly online magazine.