The year 2000 has achieved the dubious honor of being called the worst year for movies ever. That’s a pretty strong accusation, but the evidence seems to back it up. There were the usual bloated and vapid action epics (Gone in 60 Seconds, Charlie’s Angels), inane and dithering horror flicks (Scream 3, Blair Witch 2) and, most offensive, the shameless “give me an Oscar” antics of such manipulative windbags as Pay It Forward and The Patriot.

Yes, it is pretty easy to get cynical, to believe that after one last hurrah, the death of cinema is really here. But, to quote the tagline of one of last year’s masterpieces, “look closer” and you’ll find several diamonds amidst the rough.

Despite Hollywood’s unmatched carelessness, some brilliant films slipped through the cracks. Steven Soderbergh with Traffic and Erin Brockovich delivered the biggest studio double whammy since Spielberg dropped Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park on audiences in 1993. Roger Zemeckis followed suit with the only slightly less successful double effort of What Lies Beneath and Cast Away, while Cameron Crowe and Ridley Scott made triumphant comebacks with Almost Famous and Gladiator, respectively, and M. Night Shyamalan’s criminally under-appreciated Unbreakable proved the 30-year-old wiz isthe real thing.

On the indie scene, cinema was alive and furiously kicking. Ang Lee brokel anguage barriers with the impossible-to-hate Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Ken Lonergan reinvented the familial drama with the breathtaking You Can Count on Me, Claire Denis broke through taboos and into a place of unrivaled profundity with Beau Travail, and Jim Jarmusch fused a brand new, uber-cool style of east meets west stoicism with Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. So it really wasn’t that bad of a year, but Hollywood, don’t pat yourself on the back—it could have been a lot better.

1. Traffic

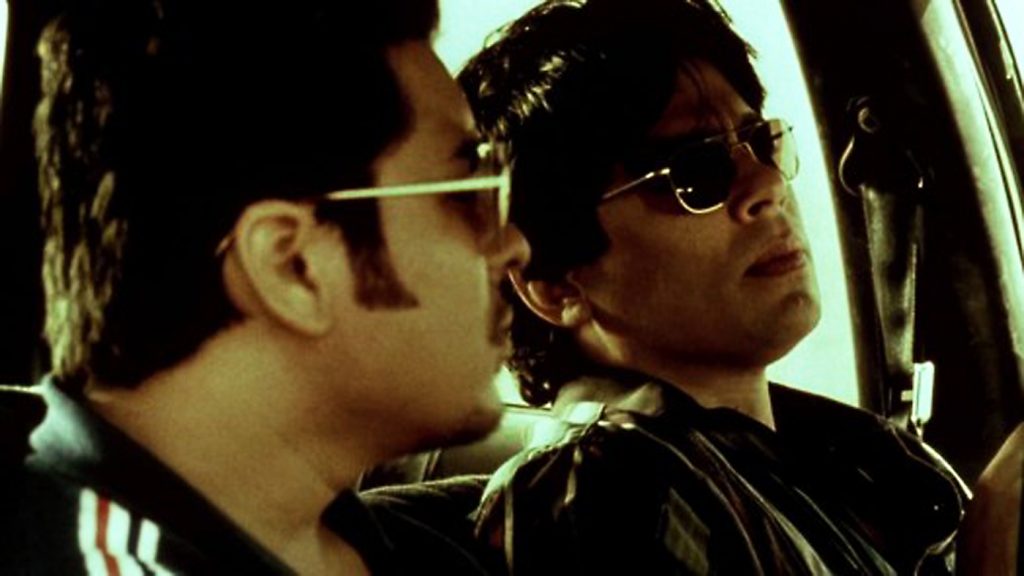

Traffic has been called a docudrama. But to me, that’s an insult to the film’s greatness, because any film as emotionally affecting as Traffic can’t be pigeonholed into a simple genre. At the same time, Traffic is a docu-drama in the fullest sense of the word. Like the best documentaries, every moment of Traffic feels like a terrifying revelation,like you’re seeing things you never knew existed and never wanted to see, but can’t take your eyes off the screen.

Weaving three revealing and blistering expository tales of the drug problem in America, Traffic shows the horror of drugs in unflinching detail. But what makes Traffic a great movie, in the vein of Short Cuts or Boogie Nights, is its ever-present humanity. Anchored by the magnificent performance of Benicio Del Toro (perhaps the most supple and heartbreaking since Martin Landau in Ed Wood), Traffic shows the futility of the drug war as well as its earnest soldiers, blindly fighting even after the sun goes down.The best movies are the ones that don’t end when the credits role,the ones that stay with you for days. For me the soldiers, villains, and victims of Traffic live on with me, and I love them all.

2. You Can Count on Me

You Can Count on Me was the year’s best thriller. I say “thriller” not in the conventional sense, but in the way the movie was so completely engrossing in showing real people, flaws and all, doing real things. Most familial dramas have the groan-worthy hysterics of a bad Lifetime movie. You Can Count on Me’s director and writer, Ken Lonergan, opted for a far more effective, subdued approach.

The film also featured the two best performances of the year. Laura Linney and Mark Ruffalo are siblings orphaned at a young age who have raised each other. Now one is controlling and neurotic, the other irresponsible and depressed. Linney, an actress I have usually found screechy and cloying,has the restraint and feeling of a young Meryl Streep. Mark Ruffalo, in what I call the greatest performance of the last five years, is so mesmerizing,so realistic, and so fascinatingly complex it’s scary. You Can Count on Me does not seem epic, but it is in the way it tackles a canvas of emotions that most movies wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole. Not since the heyday of Bergman and Ashby has there been a director with this much feeling for his characters, and Lonergan, at the young age of 38, seems to be the first real humanist of the new millennium.

3. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Saying that a movie “takes you somewhere else” seems like a failed hook for the latest behemoth Hollywood franchise vehicle. CrouchingTiger, Hidden Dragon, a small $13 million film from Taiwan, actually did that, much more than any bloated U.S. epic, including Gladiator. Ang Lee’s beautiful, decidedly sensitive meditation on love, respect, fate versus freedom, and personal excellence is as exciting and breathtaking as anything out there.

What distinguishes it as a great film is its quiet moments. The wind on mountain evergreens, Li Mu Bai practicing his martial arts, a quiet scene of action and transcendence, Jen and Lo beneath a desert sky,and Bai and Shu Lien’s tentative touch, perhaps the most romantic moment of the year. Lee does for kung fu movies what the Wachowski brothers did for sci-fi: reinvent, reinvigorate, and take it beyond its glitzy, geek roots to a place of real cinematic brilliance.

4. Unbreakable

Receiving middling box-office sales, mediocre reviews, and indifferent audience reactions, Unbreakable was hardly the triumphant follow-up to The Sixth Sense director M. Night Shyamalan boasted it would be. Now deemed a victim of hubris, Unbreakable might end up being the blemish of Shyamalan’s career. But for me, Unbreakable was the most hypnotic movie of the year. In the vein of Blue Velvet, Manhunter, and The Silence of the Lambs, Unbreakable tackles archetypal themes with an air of ambiguity, as if the director is saying we should be scared of the things we call normal. Much more kid-friendly than the aforementioned films, Unbreakable had comic-book elements that were laughed off as silly. But name another comic book film that incorporates a midlife crisis and a real romantic relationship.

Bruce Willis as the hero is admirably understated, and Samuel L. Jackson as a haunted muse gives one of the most unforgettable performances of the year. The real star, however, is Shyamalan, who with deftness and skill can shift from familial drama to an intense pursuit of serial killer. Originally, this was supposed to be the first of a trilogy. Tragically, we’ll probably never see the other two. So instead let’s just sit back and watch it influence every comic book film of the next 20 years.

5. Beau Travail

In Beau Travail young, built men sweat, grapple, and share almost everything with each other. In the hands of a lesser director, the temptation to accentuate the homoeroticism of the film would have been too much. Claire Denis seems thoroughly uninterested in doing that, and instead crafts one of the most thoughtful and sensitive meditations on masculinity, nobility,and yes, flaming out versus fading away.

The weary Lieutenant Galoup (Denis Lavant in one of the year’sgreat performances) was once a force to be reckoned with. Now, cast outin the middle- of-nowhere-colony of Djibouti, Galoup sees himself turning into his dissipated and aimless Commander (Michel Subor). When the charismaticS entain (Gregoire Colin) arrives, Galoup sees a haunting reflection of his past excellence—and can’t stand it. The dialogue is sparse as Denis focuses on movement, sound, and visuals. Fusing opera, dance tracks, and the cultural music of Djibouti with the starkly beautiful landscapes and throbbing night clubs, Denis crafts a heady and sensual experience. By the end of the film we feel we know the men like good friends,even though most of them haven’t said a word. Barely released in the states, this one will be a trick to find at video stores, but seekit out: few films cut as close to the heart of cinema as this one.

6. Before Night Falls

Painter Julian Schnabel’s first film, Basquiat, was a pretentious mess posturing as a profound art film. His second film is everything Basquiat was not: quiet, unpretentious, and deeply affecting. The story follows gay novelist Reinaldo Arenas as he tries to survive post-revolution Cuba,where among other things he is persecuted for his sexuality.

Schnabel could have made a grandstanding film about free speech and fascism, but instead he does something much more interesting. Oh, he shows th eterror of the Cuban regime and the importance of art, but more than that,he gets inside the mind of a true artist, revels in the innocent pleasure of enjoying beauty, and reveals the process of creation with a striking authenticity.

Javier Bardem, who looks like a Spanish Robert Downey Jr., is Arenas. His performance is one of such simplicity and force that I cannot imagine the real person looking or acting any differently. Schnabel uses his artistic instincts to craft the most beautiful film of the year. From a broken down cathedral with an air balloon in it to a gorgeous ride through snowy New York, Schnabel clashes beauty with pain and gives us a dreamlike movie as lucid as real life.

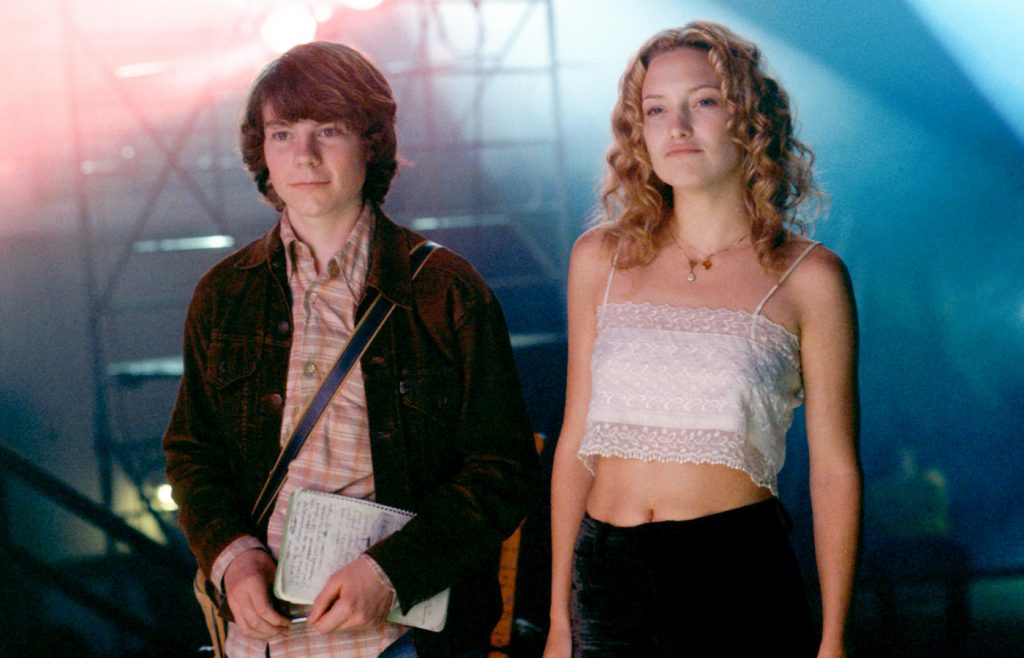

7. Almost Famous

Almost Famous, like You Can Count on Me, made me gasp at the authenticity of its characters and situations. Perhaps that’s because most of the stuff in the movie actually happened. Cameron Crowe, who has become the warmest director not to succumb to sentiment, traveled with bandsl ike Led Zeppelin and The Allman Brothers as a teenager, writing what he saw. This is his most personal story and boy, does he know how to tell it.

The beauty behind Almost Famous is that it understands both the decadence and greedy narcissism and the innocent, joyous fun of rock ’n’ roll. Aside from Iain Softley’s Backbeat, I don’t know of any other fictional rock movie that does that.

Patrick Fugit is William Miller, Crowe’s inquisitive and instantly likeable alter ego. Jason Lee and Billy Crudup are the warring leaders of the dead-on accurate band Stillwater, and Kate Hudson is the girl they all love. The movie is episodic in the sense that it is not directly linear, but by the end of the film the characters seem all the more vivid. Like the best character pieces, I left Almost Famous feeling that I learned something about myself.

8. Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Jim Jarmusch still embodies the true American independent spirit. Throughout his career he has constantly subverted and reinvented genres. In 1984 he turned the screwball comedy into a laconic Zen experiment of me-generation aimlessness with Strangers in Paradise. In 1986 he made the chain gang flick Down by Law into a sublimely silly hipster epic. And in 1995 Jarmusch perverted the western into the head-trip of a philosophy grad student with Dead Man.

It was inevitable that Jarmusch would eventually forge his own genre.Ghost Dog is precisely that, the very first Zen Samurai, hip-hop gangster, screwball postmodern comedy. Needless to say, the potential for disaster was off the charts. That is why Ghost Dog is such an achievement—no tonly a deft comedy, Ghost Dog actually said something, refrained from pretension, and damn, if it wasn’t cool. Not cool in the way that one of those horrible Guy Ritchie movies are, but cool in the sense of seeing something new and fresh. Anchored by Forest Whitaker’s magnetic performance and with the year’s most original score (by rap impresario RZA), Ghost Dog is one of the few movies I would love to see as a sequel.Knowing Jarmusch’s maverick style, that will probably never happen, but Jarmusch’s maverick style is exactly what makes him a national treasure.

9. Cast Away

Many critics complained of Cast Away’s third act problems. What did they expect? A happy ending? Tom Hanks dies on the island? Cast Away is a complex movie, and anything less than a complex ending would be unfair to the rest of the story.

A lot of people have complained that 2000 was the year that Hollywood hit an all-time low. How can that be true when it was also the year of two of the most original and daring Hollywood movies of the decade—Traffic and Cast Away?

In Cast Away, Tom Hanks’ Chuck Noland spends four years on a deserted island and learns how to live. Instead of trying to analyze Chuck’s transformation, the movie simply shows him surviving: learning to make fire to keep warm, to spear fish for food, and to bear the hardest trial of all, loneliness, by painting a face on a volleyball and calling it Wilson. In Tom Hanks’ extraordinary performance, Chuck’s plight is rendered with heartbreaking immediacy. Was there a sadder scene this year than Chuck’s tearful parting with Wilson? Cast Away shows the loneliness of isolation, but also, amazingly, the loneliness of community as well. The film’s biggest revelation is that maybe that’snot a bad thing.

10. Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?

Some people love the Coen brothers, others detest them, but no one can deny that there is no one else like them in film. Their latest opus, Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? has divided critics more than any other Coen film since Barton Fink. The naysayers have called it a dehumanized experiment in unbearable cheekiness, the supporters of the film have deemed it a miracle of old genres and new sensibilities.

For me, Oh Brother is a sly testament to the power of music and cultural roots. Bearing one of the best soundtracks ever, Oh Brother feels like just that, an episodic tapestry woven together by a common thread of inspiration.

The story, very loosely based on The Odyssey, follows Everett Ulysses McGill (a never better George Clooney) as he tries to escape from prison and make it home to his wife Penny (Holly Hunter). Although classically Coen (the so-clever colloquial dialogue, the barrage of over-the-top caricatures,etc.), the film is invigorated by the fervor everyone involved brings to it. Clooney is undeniably fiery and charismatic, and his prison cronies, played by Tim Blake Nelson and John Turturro, provide colorful support.Without the music and the film’s gorgeous cinematography, Oh Brother would have been an amusing but mediocre screwball comedy. With those elements, the film is a pleasurable oddity, a soulful farce, with as much spirit as spittle.

Worst Movies of 2000

1. Pay It Forward

The fact that Pay It Forward is the most emotionally indulgent and manipulative film since Simon Birch would be enough to make it on this list, but Pay It Forward’s offenses stretch to far darker places. Pay It Forward succumbs to, even promotes, the most gratuitous grandstanding of maladies and tragedies I have ever seen. Every character has to be damaged in the most extreme ways (Kevin Spacey can’t just be a burn victim, his dad had to set him on fire). Why such talent (Kevin Spacey, Helen Hunt, Haley Joel Osment) got on board this project I will never know. I do know this: avoid Pay It Forward like the plague. Even if you have a penchant for three-hankie pictures, this one goes too far.

2. Blair Witch 2: Book of Shadows

The first one was clever, scary, and original. This one felt like a rejected pilot for a Fox horror show. Less a film than a desperate attempt to start a franchise, Blair Witch 2 combined the worst aspects of indie films (painstakingly hip dialogue, a self-consciously dark soundtrack) with the worst aspects of Hollywood ones (a lumbering plot, wooden acting) to the point where you couldn’t even laugh at it. It just sucked.

The Cell

The Cell feels like someone saw a Nine Inch Nails video and decided to make a feature length film of it. While in video form, this style of baroque darkness, disturbing images, and violent colors is interesting, in a film it is ridiculous. Add to the fact that The Cell ripped off almost every serial killer movie ever and that the actors’ performances were one expression only (Jennifer Lopez concerned! Vince Vaughn haggard! Vincent D’Onofrio scary!) and you get a movie memorable only for a foul scene of graphic disembowelment. Yuck.

The Patriot

Sure, this eagerly noble epic had some good things about it (cinematography, fight scenes, etc.), but at its core it was the gross rah-rah propaganda of filmmakers whose greatest goal seems to be getting invited to the White House. I don’t know what bothered me most: the ridiculous and flat-out inaccurate portrayal of African Americans at that time (they were actually free people working the land!), the insane villainy of the British (Jason Isaacs’ antics were firmly entrenched in Snidley Whiplashville),or the corny script, reeking of sentimental pap. Whatever it was, it’s no surprise The Perfect Storm beat The Patriot at the box-office. At least that one had good effects.

Charlie’s Angels

The most impressive thing about this movie was the hype. With kickass trailers, a slew of product placements (sunglasses, cell phones), and the film’s stars constantly giggling about how much fun they had making it, Charlie’s Angels looked to be the joyride the summer had deprived us of. Instead, it was inane, derivative, and flat out stupid.Not the sleek look, not the “hot soundtrack,” not even the film’s greatest special effect—three beautiful actresses—could save it from a horrible script and frenzied direction. In the end it was just an over-inflated episode of VIP.